Deuterium labelling by electrochemical splitting of heavy water

Abstract

Deuterium incorporation is crucial in organic synthesis and has wide applications in the pharmaceutical industry. State-of-the-art H/D isotope exchange and chemical defunctionalization for deuterium incorporation suffer from significant drawbacks, including expensive deuterium sources, low deuteration efficiency and poor selectivity. In this perspective, we highlight an alternative pathway for forming C-D bonds by electrocatalytic heavy water splitting (D2O) under mild conditions. In addition, the intrinsic mechanism and examples of the synthesis of deuterated pharmaceuticals are discussed in detail. Finally, we present the challenges facing this field and provide an overall perspective on future research directions.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Since the discovery of deuterium by Urey et al.[1] in 1932, deuterated compounds have been extensively employed in various applications. The growing interest in catalytic C-H activation and deuterated compounds as references in mass spectrometry led to the rapid development of this field in the mid-1990s[2-4]. Compared to their C-H isotopologues, deuterium incorporation can improve metabolic clearance and toxicity profiles[5,6], thus allowing for effective treatment at a lower dosage. Tremendous efforts have been devoted to the synthesis of deuterated pharmaceuticals, including the first US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved deuterated drug in 2017[7,8].

Transforming a C-H bond to a C-D bond is a straightforward process, which primarily involves H/D isotope exchanges (HIE) with metal-catalyzed or acid/base-promoted C-H bond activation[9-11]. Such a HIE strategy offers inherent advantages by the direct incorporation of deuterium without prefunctionalization or alteration of the molecular structure[12,13]. Nevertheless, practical challenges remain, including undesirable deuteration ratios, high-cost deuterium sources and the difficulty of controlling the deuteration sites with the use of reactive deuterated reagents (e.g., D2, CD3CN, CD3OD and DMSO-d6) under harsh conditions

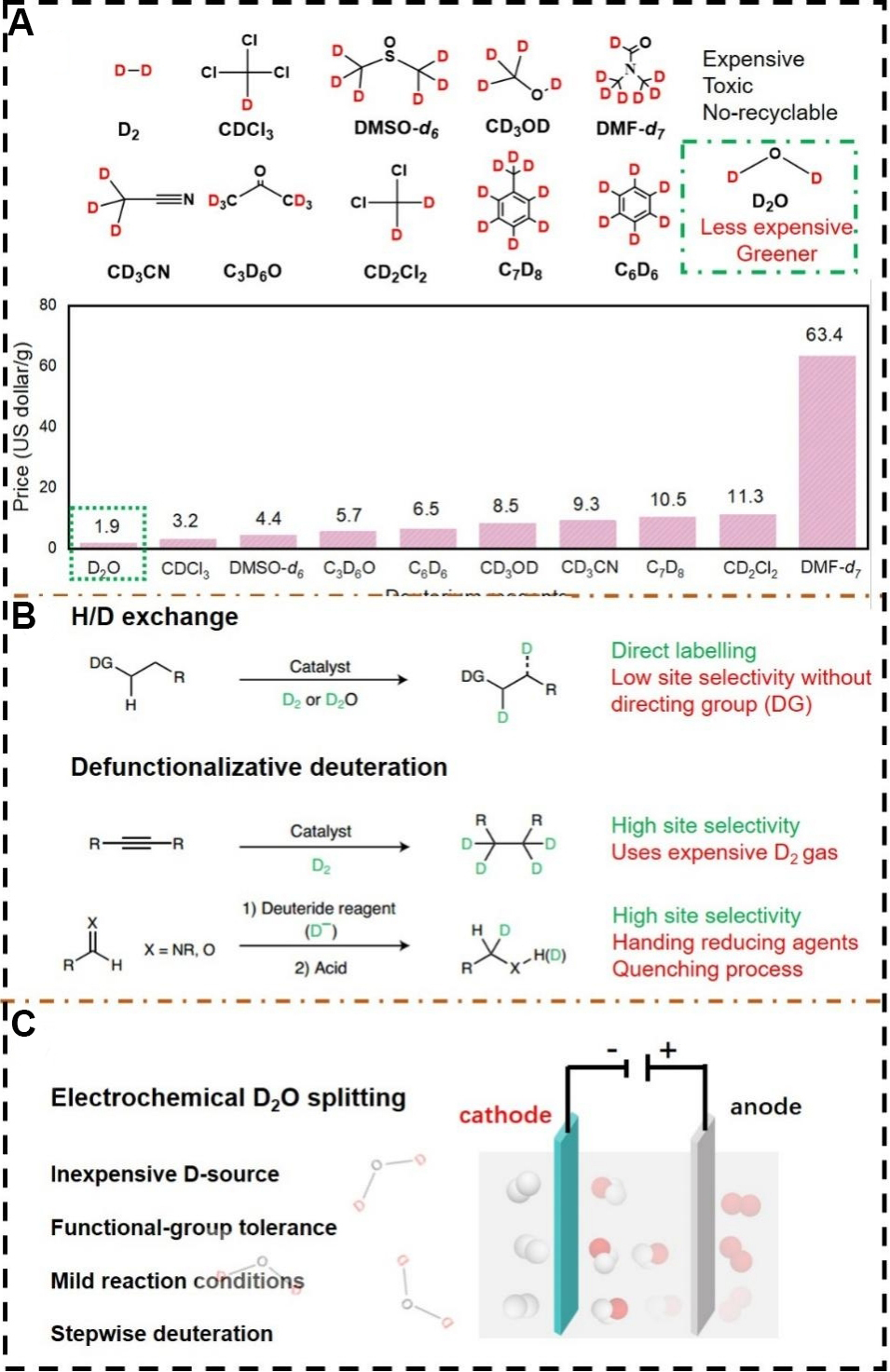

Figure 1. (A) A selection of conventional deuterium sources and their corresponding prices. (B) Comparison between the benchmark H/D exchange and defunctionalization-based deuteration. Modified with permission from ref.[33] (Copyright 2020 Nature Publishing Group). (C) Schematic of electrochemical deuteration by heavy water splitting.

In this regard, defunctionalization-based deuteration through precise conversion of a specific functional group to deuterium at target sites is promising in the pharmaceutical industry. Deuterium is installed by deuterohydrogenation of the unsaturated bonds or deuterodehalogenation of carbon-halogen bonds, offering excellent site selectivity, as shown in Figure 1B[23,24]. In general, deuterium gas (D2) as the deuterium source is activated in the initial step for reductive addition across the unsaturated bonds[25-27], where complete deuteration can be achieved with stoichiometric amounts of the deuterium transfer reagents. The major challenge lies in the use of inconvenient and expensive D2 gas, where on-site generation from D2O or other sources is highly preferred. For deuterodehalogenation, the reaction proceeds following the order of

In line with the defunctionalization strategy, deuterium labelling by electrochemical heavy water (D2O) splitting affords a greener, safer and more efficient method [Figure 1C][33] than conventional H/D exchanges or difunctionalization-based deuteration with strong reductive reagents. This electrochemical method allows the use of electrons as a green reductant source and can be readily controlled by adjusting external parameters, such as the electrolytes and applied voltages, as well as by materials engineering of the catalyst. This approach has been successfully demonstrated for the reductive deuteration of halides[34-36], alkenes[37,38], alkynes[39], unsaturated carboxylic acids[40] and deuterated methylation of nitroarenes, as shown in

Figure 2. (A) Schematic of substrate scope of electrochemical deuteration. (B) Electrochemical series of common organic functional groups.

In this perspective, we present the frontiers of electrochemical deuteration from underlying mechanisms to novel reactor designs and provide our perspective on industrial deployment for the synthesis of deuterated pharmaceuticals.

HEAVY WATER SPLITTING AS A GREENER OPTION FOR CONTROLLABLE DEUTERATION

Figure 2B depicts a comparison of the standard electrode potential of the water splitting reaction and various reducible functional groups. Among the numerous unsaturated bonds, alkynes (C≡C) are the most active in terms of reduction potential and can be readily semi-deuterated to d2-alkenes prior to water splitting. The conversion of semi-deuterated alkenes into fully deuterated alkanes is much more challenging due to their shortened bond lengths, which require a more negative potential[39]. The nitro functionality is also a reactive motif in electrochemical deuteration. Potentially reducible C-Br, C=O and C=C groups were well preserved in the products during nitro reduction according to previous reports[43,44].

For organic halides, the C-I bond is relatively easy to dissociate even at mildly reductive potentials, while the cleavage of C-F bonds is almost impossible in the water splitting window. Stepwise deuteration could be realized whenever multiple halogens are involved and the sequence is predictable based on the difference in C-X bond dissociation energy[32]. The C=O functionality (aldehydes or ketones) is usually less reactive than C-I or C-Br bonds but more reactive than the C-Cl bond[33]. The deuteration of C=N bonds (imine) to value-added deuterated amines (-ND2) is viable at a slightly more reductive potential. Finally, nitriles (C≡N) can be fully deuterated to produce primary amines and valuable α,α-dideutero analogues, despite their much more reductive potentials than water splitting[45-47].

Bearing the fundamental similarities in the atomic-level cooperative interaction between the electrocatalyst and absorbents (e.g., D*), knowledge from the well-documented hydrogen evolution reaction (HER)[48,49], carbon dioxide reduction reaction (CO2RR)[50] and nitrogen reduction reaction[51] can be leveraged to design a successful catalytic system for electrochemical deuteration. This primarily involves optimization of the adsorption strength of H*ads (D*ads) and organic substances on the surface of the electro-catalyst to tune the activity and selectivity[52,53]. The mechanism can be monitored by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and linear sweep voltammetry, in which the shape of the curve together with the intensity and location of the redox peaks provide key evidence on the (de-)adsorption process[54,55]. Substantial efforts have been devoted to regulating the catalytic activity by tailoring the electron structure and state of the d-band center through doping, alloying, defect and strain engineering. For instance, Wu et al.[39] reported a phosphorus-doped palladium nanowire (Pd-P) cathode for selective semi-hydrogenation (deuteration) of terminal and internal alkynes using H2O(D2O) as the H(D) source. The CV pattern in neutral conditions displays a weakened H* adsorption after the addition of alkyne, indicating the competitive coverage of alkyne on the H*ads sites. Density functional theory calculations further confirm the preferred adsorption of alkynes against H*ads on the Pd-P alloy, leading to higher Faraday efficiency (FE) and selectivity than conventional Pd catalysts.

In addition to appropriate catalyst designs, the reaction conditions also play a significant role in the product distribution. For instance, Kurimoto et al.[33] observed a current-dependent selectivity in alkyne deuteration. At a lower current density of ~40 mA cm-2, the semi-deuterated product (phenylacetylene-d2) was predominant (~80%) with < 5% of fully-deuterated product after 24 h. Further increasing the applied current to ~80 or ~120 mA cm-2 dramatically accelerates the deuteration process, generating a > 95% yield of the corresponding alkane-d4 within 8 or 4 h, respectively. This supports the strong correlation between the surface coverage of D*ads on the catalyst and deuteration selectivity, where a chemoselective process should be conducted at low current density (low D* coverage). Notwithstanding the lower efficiency and slower reaction kinetics, more thermodynamically challenging functionalities (C=O bonds in aldehydes and C=N bonds in imines) can also be deuterated under specific electrochemical conditions[33]. In another instance, Chong et al.[41] demonstrated the tunable reduction of nitroarene to azoxy, azo and amino compounds by simply altering the applied potential. Using a cobalt phosphide nanosheet as the cathode material, a higher potential leads to the formation of aniline (> 99% selectivity and conversion), while azoxybenzene is formed preferentially at lower potentials. Such selectivity is also related to the surface concentration of deuterium. More importantly, the electrochemical method exhibits wide functional group tolerance because it prevents unfavorable self-coupling reactions among the C-Br, C=O and C=C functionalities that are prevalent in non-electrochemical strategies, thus providing a green and controllable option for deuterium installation[43,56].

In addition to the deuteration of unsaturated bonds, the cleavage and deuteration of carbon-halogen bond represents another major type of difunctionalization-based deuteration[57,58]. Owing to the benefits of regulating the selectivity by external voltages, the electrochemical method offers the capability of promoting multiple deuteration processes. Zhang et al.[32] reported the electrosynthesis of deuterated chemicals using homogeneous palladium acetylacetonate [Pd(acac)2] with high activity and FE. By regulating the applied voltages, the bromines located at the sp2 and sp3sites can be precisely substituted by deuterium atoms. For example, D incorporation within the p-, o- and m-bromoacetophenones required different voltages of -2.55, -2.70 and -2.80 V, respectively. For multi-substituted organohalogen compounds, stepwise deuteration can be achieved under different voltages due to the difference in the strength of the C-X bond, e.g., the deuteration of iodo-, bromo- and chloroarenes can be achieved at -2.45, -2.70 and -2.90 V, while leaving other electron-donating or withdrawing substituents intact during the course of the electrosynthesis[32]. Such a strategy was further extended to pharmaceuticals, such as D-dapsone [(7) in Figure 3][36].

Hence, by controlling the electrochemical parameters, deuterium can be readily and precisely installed at the desired position of interest. To uncover electrochemical reaction mechanisms, in situ spectroscopy technologies are typically employed to detect the reaction intermediates. In situ Raman and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy could be used to observe some specific intermediates, like *CO and *CHO in the CO2RR, which are shifted toward lower wavelengths, owing to the replacement of hydrogen by deuterium. In contrast, detection of the active D* (or H*) in both Raman and FTIR spectroscopy is very challenging due to its short lifetime and very weak signal. It would be possible with benchmark surface enhanced Raman scattering or shell-isolated nanoparticle-enhanced Raman spectroscopy to enhance the Raman signal from the dissociation of interfacial (heavy) water on a metal substrate to form the M-H* (or M-D*) intermediate.

UNIVERSAL APPLICABILITY IN THE DEUTERATION OF COMPLEX MOLECULES

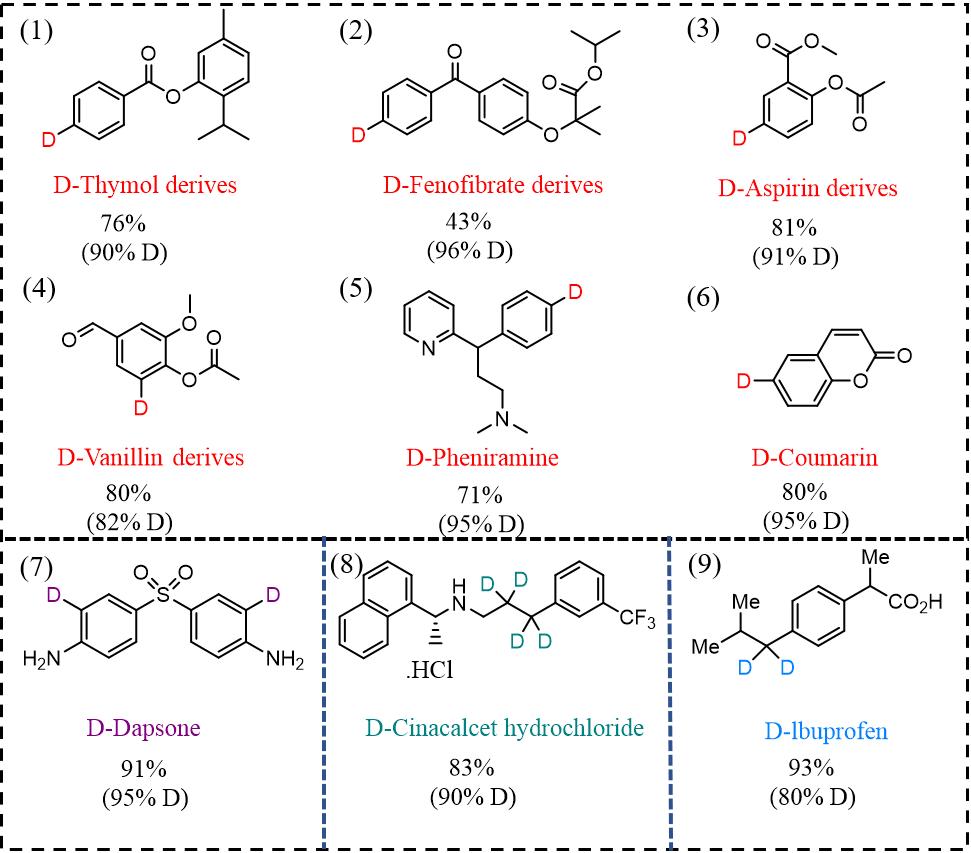

Due to its tunability and ease of operation, electrochemical deuteration by heavy water splitting can be employed in the synthesis of many deuterated pharmaceuticals and complex molecules, as shown in Figure 3. We now present a number of case studies of such applications.

Case 1

Cinacalcet hydrochloride is an FDA-approved parathyroid hormone regulator in the calcimimetics class, which is used for the treatment of secondary hyperparathyroidism by increasing the sensitivity to calcium, thus inhibiting the release of parathyroid hormone and lowering hormone levels within a few hours[59]. Its deuterated variant can prolong the half-life and reduce the dosage or frequency of the drug to minimize the risk of hypotension, heart failure or arrhythmia.

Deuterated cinacalcet hydrochloride was synthesized through the electrochemical deuteration of an alkyne in an undivided cell using 1 M D2SO4 in D2O as the electrolyte, a palladium-modified membrane as the cathode and Pt mesh as the anode. The d4-alkane was obtained in high yield (> 99%) and deuterium incorporation (> 90%) after 24 h at a constant current of 100 mA. Through the subsequent Dess-Martin oxidation and reductive amination, d4-cinacalcet hydrochloride was obtained with ≥ 90% deuterium incorporation and 83% yield. Compared to traditional deuteration using D2 as the deuterium source, the electrochemical method using D2O allows for site-selective installation of four D atoms with only 5% of the original cost[33]. Furthermore, the deuterated sites in the electrochemical reaction are different from those reported in the HIE or difunctionalization-based deuteration protocols, which could facilitate metabolism studies.

Case 2

D-Pheniramine (5), D-coumarin (6) and their derivatives [D-vanillin (4), D-thymol (1), D-fenofibrate (2) and D-aspirin (3)] are among the most successful deuterated molecules prepared through electrochemical deuteration. These compounds have been synthesized in high yields on a gram scale through the difunctionalization and transformation of halides[32]. Taking D-aspirin as an example, the traditional method involves the use of deuterated sodium hydroxide in the presence of a Raney Ni-Al alloy, followed by extraction, acetylation and recrystallization to produce 3,4,5,6-d4aspirin with poor deuteration efficiency and site selectivity. According to Su’s report, the 5-d1-aspirin derivatives were synthesized by debromination of the corresponding 5-Br analogues in a divided cell with a graphite working electrode and an electrolyte containing heavy water, palladium acetylacetonate, Na2SO4 and acetonitrile. A high isolated yield (81%) and deuterium incorporation (91%) were achieved using a constant voltage of ~3.1 V and a reaction time of ~8 h under an argon atmosphere. The Pd(acac)2 homogeneous catalyst in the electrochemical process could activate the substrate to enhance the deuteration performance, which is safer and more controllable than the use of flammable Raney Ni.

Case 3

Ibuprofen (9) is among the most widely used analgesic-anti-pyretic-anti-inflammatory drugs, similar to aspirin and paracetamol in non-prescription over-the-counter medicine. A general procedure for the deuterium labelling of ibuprofen is by alkaline treatment in D2O under reflux conditions for a few hours. Using this method, monodeuterated ibuprofen was obtained via isotopic exchange of the proton located at the α-position of the side chain with low deuterium incorporation (50%)[60]. Using an unconventional tandem setup, Ou et al.[40] demonstrated that deuteration at the benzyl (sp3 C-H) sites could be accomplished with a broad scope and excellent chemoselectivity under mild conditions. D2 gas was produced on-site through the electrochemical splitting of D2O and subsequently used for the reductive deuteration of nitriles to furnish primary amines and valuable α,α-dideutero analogues at > 90% deuterium incorporation in another chemical compartment. This outperforms earlier efforts in partial deuteration by the reductive amination of ketones or aldehydes in D2O and allows for a much safer and efficient practice than direct hydrogenation using D2 gas[61]. Moreover, the method can be used to prepare lbuprofen-d2 on a gram scale.

ENERGY-RELATED CONSIDERATIONS AND REACTOR DESIGNS FOR INDUSTRIAL DEPLOYMENT

In addition to deuterated pharmaceuticals, electrochemical deuteration is promising for the production of deuterated small molecules, such as CD3OD, C2D5OD and C2D4. In particular, the deuterium-incorporated CO2RR or CORR offers high FEs and current densities in benchmarking flow devices and high deuteration incorporation efficiency (i.e., 100% D for the production of deuterated formic acid). Alternatively, such deuterated small molecules can be accessed by the electrochemical deuteration of acetylene to C2D4 in D2O, the electrochemical water-gas shift reaction and the dehalogenative deuteration of organic halides (CHCl2 or CHCl3)[62-64].

While significant advances have been made in electrochemical deuteration, the energy-related aspects of the entire electrochemical process need to be considered for their successful translation to industrial applications. This includes the suppression of side reactions to improve the FE, recycling of unused heavy water for cost reduction and better reactor designs that integrate with state-of-the-art electrolyzer technologies to reduce electricity consumption. Herein, we provide a short perspective on these aspects that goes beyond deuteration chemistry.

Utilization efficiency of heavy water

For electrochemical systems using D2O as an electrolyte, hydrogen (deuterium) evolution is an inevitable side reaction due to the low energy barrier for self-coupling of the H (D) intermediate. Compared to hydrogenation, the kinetic isotope effect typically results in slower kinetics and thus lower efficiency to install deuterium under the same reaction conditions. FE is a key indicator to evaluate the efficiency in the electrochemical deuteration process[65,66]. According to the electrochemical palladium membrane reactor, the initial current efficiency of deuteration is considerably low (17%) due to the formation of D2 gas[33]. The influence of such side reactions becomes more significant at elevated current densities, owing to the attractive forces between the positively charge proton cation and the negatively charged electrode surface, which will eventually diminish the cell efficiency when a full proton coverage is achieved[67,68].

Previous research on the HER indicated that the HER activity is directly related to the dissociation energy of water and the adsorption energy of a proton on the catalyst[69,70]. Therefore, the introduction of an energy barrier in either step could potentially eliminate competitive reactions. Another possibility for minimizing the HER is phase separation between organic substances and D2O by lipophilic electrode modification or a non-aqueous electrolyte, where the electrode reaction predominately occurs in the organic phase to achieve high efficiency for deuteration[71,72]. Inspired by recent results from aqueous batteries, introducing additives in the solvent could aid in suppressing the HER activity and enhancing deuteration incorporation[73,74]. In contrast, the unused heavy water must be recycled in a practical operation. Unlike harsh chemical deuteration in organic solvents, electrochemical deuteration is carried out in an open system at ambient temperature and pressure, which enables “on-demand” production by switching on/off the voltage. Compared to homogeneous methods, electrochemical deuteration bypasses the tedious catalyst recovery step by a heterogeneous flow cell operation. The use of an aqueous electrolyte is also beneficial for the separation and recovery of deuterium oxide and inorganic electrolyte from deuterated organic compounds by solvent extraction in a tandem flow setup with one or more oil-water separators. Subsequent product purification can be achieved by continuous distillation or inline column chromatography[75].

Paired operation (anodic reaction)

For practical applications, the reductive process at the cathode is always paired with another anodic oxidation to maximize the cell productivity and energy efficiency. However, most research in electrochemical deuteration only focuses on the half reaction where deuteration occurs. The optimal catalyst and conditions under such evaluation could significantly deviate from practical conditions, whereby the counter reaction at the anode limits the cell performance[36,39,41]. For instance, oxygen evolution is the most common counter reaction in aqueous systems and has a considerably large overpotential for multiple electron transfer processes. This accounts for ~56% of the energy consumption in commercial alkaline water electrolyzer that only produces low value O2 gas in return[76]. To be practically meaningful, the anodic reaction should be carefully selected among those potentially capable of affording value-added products (such as the selective oxidation of hydroxymethylfurfural[77,78], ethanol[79] and glycerol[80]). Care should be taken to avoid the crossover of deuterated product to the anode, which can lead to undesired oxidative reactions (or vice versa). This calls for careful selection of the separation membrane in electrochemical deuteration.

Reactor design for industrial applicability

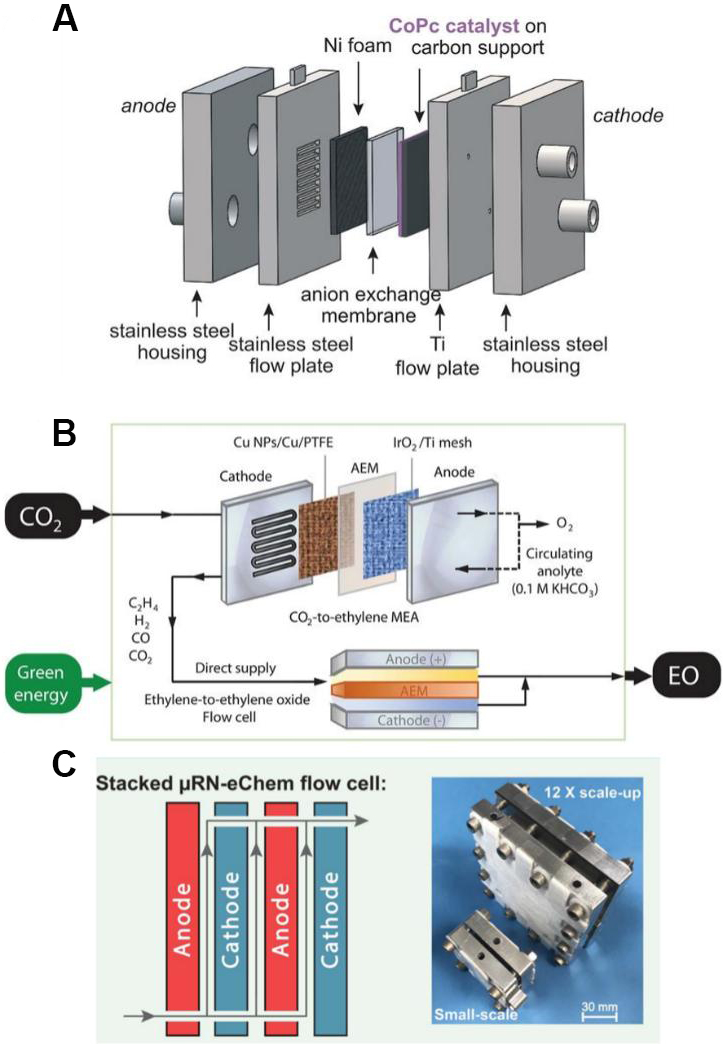

While traditional H-cell reactors have been widely used to study electrochemical deuteration, they are mass-transport limited as a result of the poor diffusion kinetics of the electrolyte. Furthermore, as a batch process, it precludes scale-up of the reaction for practical industrial purposes. To surmount the mass-diffusion limitation and increase the current density to industrial levels (500 mA cm-2), a flow electrolyzer based on state-of-the-art gas diffusion electrode technologies is highly desirable. One example of this is the micro-reactor with a parallel plate configuration in Figure 4A. Owing to its narrow inter-electrode distance (varying from mm to µm), the microreactor usually possesses a much lower cell resistance and therefore a higher current/productivity than H-type reactors[81]. A representative flow electrolyzer was developed by Leow et al.[82], as shown in Figure 4B. By using a membrane electrode assembly to achieve high current density, the injected CO2 gas can be fully converted into ethylene and subsequently oxidized into ethylene oxide in the flow cell without further purification. The novel reactor design enables a high FE of ~70% and product specificities of ~97% at 1 A cm-2, even after running the cell for 100 h.

Figure 4. (A) Schematic of zero-gap electrolyzer using gas diffusion electrode technologies. Modified with permission from ref.[81] (Copyright 2019 Science Publishing Group). (B) Stacked and scalable microfluidic redox-neutral electrochemistry flow cell. Modified with permission from ref.[82] (Copyright 2020 Science Publishing Group). (C) A practical flow cell to convert CO2 into ethylene oxide. Modified with permission from ref.[83] (Copyright 2020 Science Publishing Group).

One advantage of flow electrolyzers is that they are naturally suited to tandem synthesis. As shown in Figure 4C, Mo et al.[83] proposed a fully electrochemical two-step approach to synthesize 4-cyano-4’-pentylbiphenyl (~$100/g) from inexpensive 4-chlorobenzonitrile (< $1/g). The first homocoupling step involves the electrochemical reductive dehalogenation of 4-chlorobenzonitile to form 4-4’-biphenyldicarbonitrile (BPDN). The microfluidic flow cell allows for the gram-scale synthesis of BPDN with a higher yield (2.65 g in 24 h with a 87% yield) than a batch reaction. The second electrochemical step involves cross-coupling between BPDN and hexanoic acid under catalyst- and electrolyte-free conditions. A 12-fold increase in productivity (1.13 g of target product in 67 h) was observed by using the three-layer stacked module. Similarly, Peters et al.[84] demonstrated a 10 to 100 g scale-up for the Birch reduction by using flow cell stacks without major changes or loss in yield (72%). This underscores the importance of integrating flow cell technologies and modular operations for translating laboratorial practice to industrial applications.

CONCLUSION

In recent years, the electrocatalytic splitting of heavy water has been demonstrated as a highly effective strategy for the synthesis of deuterated pharmaceuticals. However, challenges still remain, including unexpected competitive reactions, low energy utilization of the paired reaction and a lack of good reactor design for industrial applicability. The key to addressing these challenges is to adopt a multidisciplinary approach encompassing expertise in organic chemistry, electrochemistry, materials science and flow chemistry engineering.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributionsWrote the draft: Liu J

Supervision: Loh KP

Discussed and commented on the manuscript: Liu J, Chen Z, Koh MJ, Loh KP

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipThis work was supported by National Research Foundation, Singapore for NRF Investigator Award “Graphene oxide a new class of catalytic, ionic and molecular sieving materials”, award number NRF-NRF12015-01 and the National University of Singapore Academic Research Fund Tier 1: R-143-000-B57-114.

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2021.

REFERENCES

2. Atzrodt J, Derdau V, Fey T, Zimmermann J. The renaissance of H/D exchange. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2007;46:7744-65.

4. Ribas X, Xifra R, Parella T, Poater A, Solà M, Llobet A. Regiospecific C-H bond activation: reversible H/D exchange promoted by CuI complexes with triazamacrocyclic ligands. Angew Chem 2006;118:3007-10.

6. Michelotti A, Roche M. 40 years of hydrogen-deuterium exchange adjacent to heteroatoms: a survey. Synthesis 2019;51:1319-28.

9. Atzrodt J, Derdau V, Kerr WJ, Reid M. C-H functionalisation for hydrogen isotope exchange. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2018;57:3022-47.

10. Junk T, Catallo WJ. Hydrogen isotope exchange reactions involving C-H (D, T) bonds. Chem Soc Rev 1997;26:401-6.

11. Rettner CT, Auerbach DJ. Quantum-state distributions for the HD product of the direct reaction of H(D)/Cu(111) with D(H) incident from the gas phase. J Chem Phys 1996;104:2732-9.

12. Alonso F, Beletskaya IP, Yus M. Metal-mediated reductive hydrodehalogenation of organic halides. Chem Rev 2002;102:4009-91.

13. Hatano N, Watanabe M, Takekiyo T, Abe H, Yoshimura Y. Anomalous conformational change in 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate-D2O mixtures. J Phys Chem A 2012;116:1208-12.

14. Li H, Zhang B, Dong Y, et al. A selective and cost-effective method for the reductive deuteration of activated alkenes. Tetrahedron Letters 2017;58:2757-60.

15. Than C, Morimoto H, Andres H, Williams PG. Tritium and deuterium labelling studies of alkali metal borohydrides and their application to simple reductions. J Label Compd Radiopharm 1996;38:693-711.

16. Puleo TR, Strong AJ, Bandar JS. Catalytic α-selective deuteration of styrene derivatives. J Am Chem Soc 2019;141:1467-72.

17. Zarate C, Yang H, Bezdek MJ, Hesk D, Chirik PJ. Ni(I)-X complexes bearing a bulky α-diimine ligand: synthesis, structure, and superior catalytic performance in the hydrogen isotope exchange in pharmaceuticals. J Am Chem Soc 2019;141:5034-44.

18. Yu RP, Hesk D, Rivera N, Pelczer I, Chirik PJ. Iron-catalysed tritiation of pharmaceuticals. Nature 2016;529:195-9.

19. Koniarczyk JL, Hesk D, Overgard A, Davies IW, McNally A. A general strategy for site-selective incorporation of deuterium and tritium into pyridines, diazines, and pharmaceuticals. J Am Chem Soc 2018;140:1990-3.

20. Mo X, Yakiwchuk J, Dansereau J, McCubbin JA, Hall DG. Unsymmetrical diarylmethanes by ferroceniumboronic acid catalyzed direct friedel-crafts reactions with deactivated benzylic alcohols: enhanced reactivity due to ion-pairing effects. J Am Chem Soc 2015;137:9694-703.

21. Harbeson SL, Tung RD. Deuterium medicinal chemistry: a new approach to drug discovery and development. Med Chem News 2014;24:8-22.

22. Wang D, Chen S, Wang J, Astruc D, Chen B. Base-catalyzed hydrogen-deuterium exchange and dehalogenation reactions of 1,2,3-triazole derivatives. Tetrahedron 2016;72:6375-9.

23. Zhu N, Su M, Wan WM, Li Y, Bao H. Practical method for reductive deuteration of ketones with magnesium and D2O. Org Lett 2020;22:991-6.

24. Rowbotham JS, Ramirez MA, Lenz O, Reeve HA, Vincent KA. Bringing biocatalytic deuteration into the toolbox of asymmetric isotopic labelling techniques. Nat Commun 2020;11:1454.

25. Kurita T, Aoki F, Mizumoto T, et al. Facile and convenient method of deuterium gas generation using a Pd/C-catalyzed H2-D2 exchange reaction and its application to synthesis of deuterium-labeled compounds. Chemistry 2008;14:3371-9.

26. Sajiki H, Kurita T, Esaki H, Aoki F, Maegawa T, Hirota K. Complete replacement of H2 by D2 via Pd/C-catalyzed H/D exchange reaction. Org Lett 2004;6:3521-3.

27. Chandrasekhar S, Vijaykumar B, Mahesh Chandra B, Raji Reddy C, Naresh P. Flow chemistry approach for partial deuteration of alkynes: synthesis of deuterated taxol side chain. Tetrahedron Letters 2011;52:3865-7.

28. Jinno K, Nakanishi S, Nagoshi T. Microcolumn gel permeation chromatography with inductively coupled plasma emission spectrometric detection. Anal Chem 1984;56:1977-9.

29. Narayanam JM, Tucker JW, Stephenson CR. Electron-transfer photoredox catalysis: development of a tin-free reductive dehalogenation reaction. J Am Chem Soc 2009;131:8756-7.

30. Wang X, Zhu MH, Schuman DP, et al. General and practical potassium methoxide/disilane-mediated dehalogenative deuteration of (hetero)arylhalides. J Am Chem Soc 2018;140:10970-4.

31. Ma H, Xu Y, Ding X, Liu Q, Ma C. Electrocatalytic dechlorination of chloropicolinic acid mixtures by using palladium-modified metal cathodes in aqueous solutions. Electrochimica Acta 2016;210:762-72.

32. Zhang B, Qiu C, Wang S, et al. Electrocatalytic water-splitting for the controllable and sustainable synthesis of deuterated chemicals. Science Bulletin 2021;66:562-9.

33. Kurimoto A, Sherbo RS, Cao Y, Loo NWX, Berlinguette CP. Electrolytic deuteration of unsaturated bonds without using D2. Nat Catal 2020;3:719-26.

34. Gütz C, Bänziger M, Bucher C, Galvão TR, Waldvogel SR. Development and scale-up of the electrochemical dehalogenation for the synthesis of a key intermediate for NS5A inhibitors. Org Process Res Dev 2015;19:1428-33.

35. Gütz C, Selt M, Bänziger M, et al. A novel cathode material for cathodic dehalogenation of 1,1-dibromo cyclopropane derivatives. Chemistry 2015;21:13878-82.

36. Liu C, Han S, Li M, Chong X, Zhang B. Electrocatalytic deuteration of halides with D2O as the deuterium source over a copper nanowire arrays cathode. Angew Chem 2020;132:18685-9.

37. Xiong P, Long H, Song J, Wang Y, Li JF, Xu HC. Electrochemically enabled carbohydroxylation of alkenes with H2O and organotrifluoroborates. J Am Chem Soc 2018;140:16387-91.

38. Liu X, Liu R, Qiu J, Cheng X, Li G. Chemical-reductant-free electrochemical deuteration reaction using deuterium oxide. Angew Chem 2020;132:14066-71.

39. Wu Y, Liu C, Wang C, Lu S, Zhang B. Selective transfer semihydrogenation of alkynes with H2O (D2O) as the H (D) source over a Pd-P cathode. Angew Chem 2020;132:21356-61.

40. Ou W, Xiang X, Zou R, Xu Q, Loh KP, Su C. Room-temperature palladium-catalyzed deuterogenolysis of carbon oxygen bonds towards deuterated pharmaceuticals. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2021;60:6357-61.

41. Chong X, Liu C, Huang Y, Huang C, Zhang B. Potential-tuned selective electrosynthesis of azoxy-, azo- and amino-aromatics over a CoP nanosheet cathode. Natl Sci Rev 2020;7:285-95.

42. Wang L, Neumann H, Beller M. Palladium‐catalyzed methylation of nitroarenes with methanol. Angew Chem 2019;131:5471-5.

43. Blaser H, Steiner H, Studer M. Selective catalytic hydrogenation of functionalized nitroarenes: an update. ChemCatChem 2009;1:210-21.

44. Kawamata Y, Yan M, Liu Z, et al. Scalable, electrochemical oxidation of unactivated C-H bonds. J Am Chem Soc 2017;139:7448-51.

45. Mészáros R, Peng BJ, Ötvös SB, Yang SC, Fülöp F. Continuous-flow hydrogenation and reductive deuteration of nitriles: a simple access to α,α-dideutero amines. Chempluschem 2019;84:1508-11.

46. Root DK, Smith WH. Electrochemical behavior of selected imine derivatives, reductive carboxylation, α-amino acid synthesis. J Electrochem Soc 1982;129:1231-6.

47. Zuman P. Aspects of electrochemical behavior of aldehydes and ketones in protic media. Electroanalysis 2006;18:131-40.

48. Li H, Tsai C, Koh AL, et al. Activating and optimizing MoS2 basal planes for hydrogen evolution through the formation of strained sulphur vacancies. Nat Mater 2016;15:48-53.

49. Zhang J, Wu J, Guo H, et al. Unveiling active sites for the hydrogen evolution reaction on monolayer MoS2. Adv Mater 2017;29:1701955.

50. Lin L, Li H, Yan C, et al. Synergistic catalysis over iron-nitrogen sites anchored with cobalt phthalocyanine for efficient CO2 electroreduction. Adv Mater 2019;31:e1903470.

51. Guo C, Ran J, Vasileff A, Qiao S. Rational design of electrocatalysts and photo(electro)catalysts for nitrogen reduction to ammonia (NH3) under ambient conditions. Energy Environ Sci 2018;11:45-56.

52. Wang J, Xu F, Jin H, Chen Y, Wang Y. Non-noble metal-based carbon composites in hydrogen evolution reaction: fundamentals to applications. Adv Mater 2017;29:1605838.

53. Chen Z, Liu C, Liu J, et al. Cobalt single-atom-intercalated molybdenum disulfide for sulfide oxidation with exceptional chemoselectivity. Adv Mater 2020;32:e1906437.

54. Uchida Y, Kätelhön E, Compton RG. Sweep voltammetry with a semi-circular potential waveform: electrode kinetics. J Electroanal Chem 2019;835:60-6.

55. Wang H, Sayed SY, Luber EJ, et al. Redox flow batteries: how to determine electrochemical kinetic parameters. ACS Nano 2020;14:2575-84.

56. Boronat M, Concepción P, Corma A, González S, Illas F, Serna P. A molecular mechanism for the chemoselective hydrogenation of substituted nitroaromatics with nanoparticles of gold on TiO2 catalysts: a cooperative effect between gold and the support. J Am Chem Soc 2007;129:16230-7.

57. Liu C, Chen Z, Su C, et al. Controllable deuteration of halogenated compounds by photocatalytic D2O splitting. Nat Commun 2018;9:80.

58. Zhang M, Yuan X, Zhu C, Xie J. Deoxygenative deuteration of carboxylic acids with D2O. Angew Chem 2019;131:318-22.

59. Shinde GB, Niphade NC, Deshmukh SP, Toche RB, Mathad VT. Industrial application of the forster reaction: novel one-pot synthesis of cinacalcet hydrochloride, a calcimimetic agent. Org Process Res Dev 2011;15:455-61.

60. Castell JV, Martínez LA, Miranda MA, Tárrega P. A general procedure for isotopic (deuterium) labelling of non-steroidal antiinflammatory 2-arylpropionic acids. J Label Compd Radiopharm 1994;34:93-100.

61. Hu Y, Liang L, Wei W, Sun X, Zhang X, Yan M. A convenient synthesis of deuterium labeled amines and nitrogen heterocycles with KOt-Bu/DMSO-d6. Tetrahedron 2015;71:1425-30.

62. Shi R, Wang Z, Zhao Y, et al. Room-temperature electrochemical acetylene reduction to ethylene with high conversion and selectivity. Nat Catal 2021;4:565-74.

63. Lee JH, Tackett BM, Xie Z, Hwang S, Chen JG. Isotopic effect on electrochemical CO2 reduction activity and selectivity in H2O- and D2O-based electrolytes over palladium. Chem Commun (Camb) 2019;56:106-8.

64. Cui X, Su HY, Chen R, et al. Room-temperature electrochemical water-gas shift reaction for high purity hydrogen production. Nat Commun 2019;10:86.

65. Choi S, Davenport TC, Haile SM. Protonic ceramic electrochemical cells for hydrogen production and electricity generation: exceptional reversibility, stability, and demonstrated faradaic efficiency. Energy Environ Sci 2019;12:206-15.

66. Pan H, Barile CJ. Electrochemical CO2 reduction to methane with remarkably high Faradaic efficiency in the presence of a proton permeable membrane. Energy Environ Sci 2020;13:3567-78.

67. Zhou Y, Silva JL, Woods JM, et al. Revealing the contribution of individual factors to hydrogen evolution reaction catalytic activity. Adv Mater 2018;30:e1706076.

68. Wang H, Gao X, Lv Z, Abdelilah T, Lei A. Recent advances in oxidative R1-H/R2-H cross-coupling with hydrogen evolution via photo-/electrochemistry. Chem Rev 2019;119:6769-87.

69. Yu FY, Lang ZL, Yin LY, et al. Pt-O bond as an active site superior to Pt0 in hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat Commun 2020;11:490.

70. McAllister J, Bandeira NAG, McGlynn JC, et al. Tuning and mechanistic insights of metal chalcogenide molecular catalysts for the hydrogen-evolution reaction. Nat Commun 2019;10:370.

71. De Arquer FPG, Dinh CT, Ozden A, et al. CO2 electrolysis to multicarbon products at activities greater than 1 A cm-2. Science 2020;367:661-6.

72. Wakerley D, Lamaison S, Ozanam F, et al. Bio-inspired hydrophobicity promotes CO2 reduction on a Cu surface. Nat Mater 2019;18:1222-7.

73. Cao L, Li D, Hu E, et al. Solvation structure design for aqueous Zn metal batteries. J Am Chem Soc 2020;142:21404-9.

74. Tang B, Shan L, Liang S, Zhou J. Issues and opportunities facing aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Energy Environ Sci 2019;12:3288-304.

75. Kubota SR, Choi KS. Electrochemical oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural to 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid (FDCA) in acidic media enabling spontaneous FDCA separation. ChemSusChem 2018;11:2138-45.

76. Gandía LM, Oroz R, Ursúa A, Sanchis P, Diéguez PM. Renewable hydrogen production: performance of an alkaline water electrolyzer working under emulated wind conditions. Energy Fuels 2007;21:1699-706.

77. Zhang N, Zou Y, Tao L, et al. Electrochemical oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural on nickel nitride/carbon nanosheets: reaction pathway determined by in situ sum frequency generation vibrational spectroscopy. Angew Chem 2019;131:16042-50.

78. Liu W, Dang L, Xu Z, Yu H, Jin S, Huber GW. Electrochemical oxidation of 5-hydroxymethylfurfural with nife layered double hydroxide (LDH) nanosheet catalysts. ACS Catal 2018;8:5533-41.

79. Dutta A, Ouyang J. Ternary NiAuPt nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide as catalysts toward the electrochemical oxidation reaction of ethanol. ACS Catal 2015;5:1371-80.

80. Liu D, Liu JC, Cai W, et al. Selective photoelectrochemical oxidation of glycerol to high value-added dihydroxyacetone. Nat Commun 2019;10:1779.

81. Ren S, Joulié D, Salvatore D, et al. Molecular electrocatalysts can mediate fast, selective CO2 reduction in a flow cell. Science 2019;365:367-9.

82. Leow WR, Lum Y, Ozden A, et al. Chloride-mediated selective electrosynthesis of ethylene and propylene oxides at high current density. Science 2020;368:1228-33.

83. Mo Y, Lu Z, Rughoobur G, et al. Microfluidic electrochemistry for single-electron transfer redox-neutral reactions. Science 2020;368:1352-7.

Cite This Article

Export citation file: BibTeX | RIS

OAE Style

Liu J, Chen Z, Koh MJ, Loh KP. Deuterium labelling by electrochemical splitting of heavy water. Energy Mater 2021;1:100016. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2021.19

AMA Style

Liu J, Chen Z, Koh MJ, Loh KP. Deuterium labelling by electrochemical splitting of heavy water. Energy Materials. 2021; 1(2): 100016. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2021.19

Chicago/Turabian Style

Liu, Jia, Zhongxin Chen, Ming Joo Koh, Kian Ping Loh. 2021. "Deuterium labelling by electrochemical splitting of heavy water" Energy Materials. 1, no.2: 100016. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2021.19

ACS Style

Liu, J.; Chen Z.; Koh MJ.; Loh KP. Deuterium labelling by electrochemical splitting of heavy water. Energy Mater. 2021, 1, 100016. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2021.19

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Cite This Article 19 clicks

Cite This Article 19 clicks

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.