An interpenetrating network polycarbonate-based composite electrolyte for high-voltage all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries

Abstract

The exploration of solid polymer-based composite electrolytes (SCPEs) that possess good safety, easy processability, and high ionic conductivity is of great significance for the development of advanced all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries (ASSLMBs). However, the poor interfacial compatibility between the electrode and solid electrolyte leads to a large interfacial impedance that weakens the electrochemical performance of the battery. Herein, an interpenetrating network polycarbonate (INPC)-based composite electrolyte is constructed via the in-situ polymerization of butyl acrylate, Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO), Lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulphonyl)imide, succinonitrile and 2,2-azobisisobutyronitrile on the base of a symmetric polycarbonate monomer. Benefiting from the synergistic effect of each component and the unique structure features, the INPC&LLZO-SCPE can effectively integrate the merits of the polymer and inorganic electrolytes and deliver superior ionic conductivity (3.56 × 10-4

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Currently, the development of renewable and clean energy is widely regarded as a feasible method to solve the issues of environmental pollution and resource depletion induced by the use of fossil fuels[1]. By virtue of their high energy density, lithium-ion batteries now dominate the energy storage market, from porTABLE electronic devices to the newly prospering electric vehicles[2,3]. However, the electrolytes used in traditional Li-ion batteries are always liquid organic ester electrolytes, which are volatile, flammable and can leak, leading to significant safety concerns[4]. All-solid-state lithium metal batteries (ASSLMBs), as effective alternatives to promote the intrinsic safety of next-generation high-energy lithium batteries, are gaining increasing attention owing to the employment of solid-state electrolytes (SSEs) instead of liquid electrolytes[5,6]. Furthermore, additional merits, such as desirable mechanical stability and thermal stability, can also be anticipated for ASSLMBs.

SSEs generally consist of two types: inorganic solid electrolytes and solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs)[7]. Although inorganic solid electrolytes [e.g., garnet Li7La3Zr2O12, Li1.3Al0.3Ti1.7(PO4)3, Li1.5Al0.5Ge1.5(PO4)3, Li10GeP2S12 and Li9.54Si1.74P1.44S11.7Cl0.3] possess high ionic conductivity and excellent thermal stability, their brittleness and high interfacial impedance often make it difficult to prepare products on a large scale, thereby limiting their wide application in practice[8,9]. SPEs, in contrast, demonstrate good flexibility, easy synthesis and processing, low mass density, good electrode/electrolyte interfacial compatibility, and obvious modification advantages, illustrating their considerable potential in ASSLMBs[10].

SPEs are mainly composed of a polymer matrix and lithium salts[11]. To meet the demands for practical applications, several conditions are essential:

(1) Excellent solubility with polar groups required on the polymer framework chain segment (such as -O- and -C=O) to dissolve lithium salts and transfer lithium ions;

(2) High electrochemical stability with a broad voltage window and improved energy density of the battery;

(3) High ionic conductivity and Li+ transference number t(Li+) with reduced polarization and enhanced performance during circulation;

(4) High chemical stability to ensure safety during battery operation and storage;

(5) Enhanced mechanical properties, including a high tensile strength to isolate the electrode and improve the safety of the battery and a high Young’s modulus to suppress the formation of lithium dendrites[12-14].

The most widely studied SPEs are polyether-based polymers, especially polyethylene oxide (PEO)[15,16]. However, the shortcomings of PEO-based electrolytes cannot be ignored and mainly include a narrow electrochemical window (< 3.9 V), low conductivity (< 10-4 S cm-1 at room temperature), a limited t(Li+) (< 0.2) and poor mechanical properties that weaken their usability and potential in ASSLMBs[17-19].

Compared with PEO-based electrolytes, polycarbonate-based electrolytes have a special molecular structure, which contains strong polar carbonate groups for an increased dielectric constant of the polymer that enables weakened interactions between the cation and anion, increased amounts of carriers and improved ionic conductivity[20-22]. In addition, the introduction of groups with a high dielectric constant into the main chain of the polymer can also modify the electrochemical stability window[23,24]. Therefore, polycarbonate-based electrolytes can reveal high ionic conductivity, a wide electrochemical stability window, and favorable thermal stability. In general, polycarbonate-based polymer electrolytes contain polytrimethylene carbonate, polyvinyl carbonate, and propylene carbonate. However, the amorphous structure of polycarbonate-based electrolytes leads to poor mechanical strength, which limits their practical applications[23,25]. Therefore, the development of solid polymer-based composite electrolytes (SPCEs) that combine the merits of solid inorganic electrolytes and SPEs presents a promising potential for ASSLMBs[4,26,27,28].

Herein, we report an interpenetrating network polycarbonate (INPC)-based SPCE, which is obtained through an in situ polymerization reaction of butyl acrylate, Li7La3Zr2O12 (LLZO), lithium bis(trifluoromethanesulfonyl)imide (LiTFSI), succinonitrile (SN) and 2,2-azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) based on a symmetric polycarbonate monomer. The polycarbonate monomer is first prepared through the molecular design of the polymer, which possesses the symmetrical structure of the carbon-carbon (-C=C-) double bond[29]. Taking the -C=C- double bond as the site of free radical reaction, an interpenetrating network polymer framework with high mechanical strength is then constructed[12,30,31]. Based on this premise, a precursor solution composed of a monomer, butyl acrylate, LiTFSI, SN, and AIBN is carried out to form the INPC&LLZO-SCPE. In this process, LLZO is used as an inorganic filler and AIBN is employed to initiate the in situ polymerization reaction[32,33]. The in situ polymerization can reduce the electrode/electrolyte interfacial impedance, meet the requirements of solid-state lithium batteries and simplify the battery assembly steps. The obtained INPC&LLZO-SCPE integrates the merits of both polymer and inorganic electrolytes and thus exhibits superior ionic conductivity, an impressive t(Li+), and a high electrochemical stability window. Furthermore, ASSLMBs based on LiFePO4/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li and LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li are assembled, which deliver considerable electrochemical performance.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Methacryloyl chloride, polyethylene glycol (PEG, average Mw = 400), sodium hydride (NaH), AIBN, butyl acrylate, SN, ethyl acetate, petroleum ether, tetrahydrofuran, N-methyl pyrrolidone, tetramethylsilane (TMS), poly(1,1-difluoroethylene), LiOH, La(OH)3 and ZrO2 were purchased from Aldrich Industrial Inc. LiTFSI was bought from Shenzhen Capchem Technology Co., Ltd. Polyimide (PI) film was purchased from Jiangxi Xiancai Nanofiber Technology Co., Ltd.

Synthesis of polymer monomer

The polycarbonate monomer was prepared according to the following steps. First, PEG and NaH with a molar ratio of 1:2 were dissolved into tetrahydrofuran in a round-bottomed flask, followed by cooling under an ice-water bath for 30 min. Methacryloyl chloride was then added to the above solution and a nucleophilic substitution reaction occurred under the protection of an argon atmosphere at 25 °C. The molar ratio of methacryloyl chloride, PEG, and NaH was controlled to 2:1:2. After the reaction was completed, a saturated ammonium chloride solution was added for the quenching and ethyl acetate was employed for the extraction reaction. Finally, the extracted monomer was evaporated and dried under a vacuum using a rotary apparatus, forming a colorless and transparent product.

Synthesis of interpenetrating network polycarbonate-based composite electrolyte

Typically, a precursor solution, including the polycarbonate monomer (36 wt.%), butyl acrylate (18 wt.%), LiTFSI (16 wt.%), and SN (22 wt.%) was first obtained via constant stirring for 6 h at room temperature. LLZO, as an inorganic filler (8 wt.%), and AIBN, as an initiator (0.1 wt.% monomer to initiate the in situ polymerization of the polycarbonate monomer), were then added in sequence and stirred for 12 h. Finally, the precursor solution was injected into 2032 cells in a glove box filled with an Ar atmosphere, and the PI film was used as the supporting medium for the resultant INPC&LLZO-SCPE.

Characterization

The synthesized monomer was tested using 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy on a Bruker AVANCE spectrometer in chloroform-d, and the chemical shifts were referred to TMS as the internal standard. The crystal structure of LLZO was analyzed via X-ray diffraction (XRD) with Cu Kα radiation. The synthesized INPC&LLZO-SCPE was tested by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, which was recorded over the range of 4000-500 cm-1 at 25 ℃. The surface morphologies of the INPC&LLZO-SCPE and lithium-metal anode were analyzed by field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM 6330).

Electrochemical characterization

The ionic conductivity of the INPC&LLZO-SCPE was measured by the AC impedance method. A stainless steel/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/stainless steel battery was assembled and tested on a Solartron electrochemical station 1260 + 1287 in a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz using an amplitude of 10 mV. The temperature-dependent ionic conductivity was tested between 25 and 90 °C and the value of the ionic conductivity was calculated using:

σ= L/RS (1)

The electrochemical stability window was tested by linear voltammetric scanning (LSV) with a stainless steel/SCPE/Li battery on the Solartron electrochemical station at 25 °C. The scan rate was 1 mV s-1 and the potential ranged from -1 to 6 V. The lithium transference number t(Li+) was tested by the method of DC polarization with AC impedance with a Li/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery at 25 °C based on:

t(Li+) = [IS(ΔV - Io × Ro)]/Io(ΔV - IS × RS) (2)

The interfacial compatibility between the lithium metal and the electrolyte was characterized using the calendar impedance curve by recording the values of the interfacial resistance of symmetrical Li batteries for different times at 25 °C. The ability to inhibit lithium dendrites was tested by the charge-discharge curve of symmetrical Li batteries at a constant current density. The cycling stability of the full batteries was examined using a LAND battery test system (CT2001A) at 25 °C.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

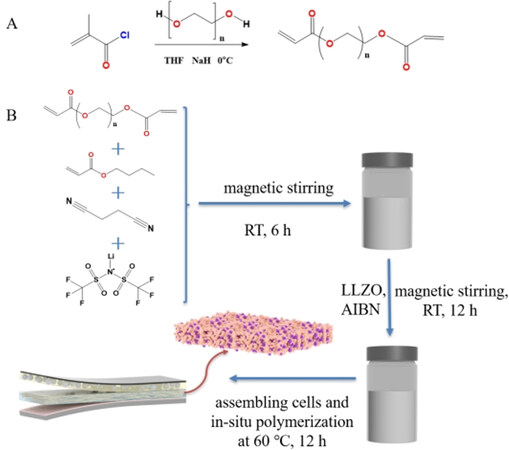

Figure 1A illustrates the synthesis route of the polycarbonate monomer with a symmetric structure through a nucleophilic substitution reaction. In this reaction, PEG, used as a nucleophilic reagent, reacts with a target molecule of methacryloyl chloride, and hydroxyl groups replace the chlorine atoms to form the polycarbonate monomer[34-36]. The symmetrical polycarbonate monomer is terminated with methacrylic acid, which possesses both ethylene oxide and carbonate units[29]. As demonstrated by 1H-NMR spectroscopy in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2, before the nucleophilic substitution reaction, the two proton peaks of 6.47 and 6.02 ppm in methacryloyl chloride (as the reaction substrate) are related to the functional group of -C=C- and another peak of 1.97 ppm can be assigned to -CH3-

An INPC is a special polymer blend that can be formed by the free radical-initiated polymerization of the symmetrical polycarbonate monomer and the soft polymer monomer of butyl acrylate[37,38]. For the synthesis of the INPC&LLZO-SCPE, the precursor solution includes the two monomers above [Figure 1B] and AIBN, which is employed as a common and efficient free radical polymerization heat initiator to initiate the in situ polymerization reaction. The symmetrical polycarbonate monomer can form polymers with an interpenetrating network structure, while the butyl acrylate can lead to linear polymers. Furthermore, the 2 monomers can also react with each other to obtain a comb polymer. Eventually, the linear and comb polymers become physically trapped in the network and provide a plasticizing effect[34].

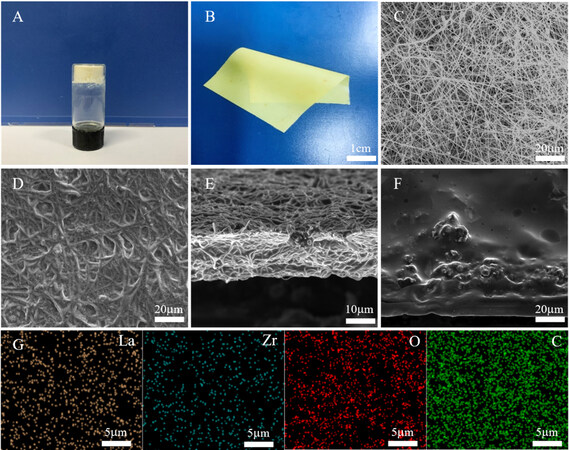

Photographs of the INPC-SPE and INPC&LLZO-SCPE are shown in Supplementary Figure 3A-B and Figure 2A-B respectively. The as-formed electrolyte film shows gratifying flexibility. In addition, the -C=C- of the free radical-initiated interpenetrating network polymerization of the 2 electrolytes was provided by the monomers with a symmetrical structure, while the linear and comb polymer reaction resulted from the monomers with a symmetrical structure and butyl acrylate[30]. Therefore, -C=C- participates in the free radical initiated polymerization. When the signal of -C=C- disappears in the INPC&LLZO-SCPE, the interpenetrating polymerization initiated by the free radical can be considered completed[39]. The FTIR spectra of methacryloyl chloride and PEG are shown in Supplementary Figure 4. It can be seen that methacryloyl chloride contains -C=C-, while PEG possesses hydroxyl and ester groups. As demonstrated in Supplementary Figure 5A and B, the FTIR spectra show that the -C=C- stretching vibration peak at 1634 cm-1 disappears during the in situ polymerization reaction and only ether oxygen and ester functional groups are observed, signifying that -C=C- becomes -C-C- and the interpenetrating polymerization is successfully completed to form an interpenetrating network polymer framework.

The surface morphology of the INPC&LLZO-SCPE is characterized by SEM. As shown in Figure 2C-E, the composite electrolyte is evenly filled in the pores of the PI film with a small thickness of less than 20 μm and the contained LLZO particles exhibit a uniform dispersion without any agglomeration. Furthermore, the INPC&LLZO-SCPE can be infiltrated on the surface of the cathode via in situ polymerization, and thus no obvious interface exists between the electrolyte and electrode, contributing to the decrease in interfacial impedance and the improvement in ionic conductivity [Figure 2F][40]. The energy-dispersive spectral mapping images of the INPC&LLZO-SCPE are shown in Figure 2G, demonstrating an even distribution of each element, corresponding to the SEM results.

Figure 2. (A) Optical images of INPC&LLZO-SCPE stored at 60 ℃ for 12 h. (B) Optical image of formed INPC&LLZO-SCPE film. (C) Surface morphology of PI film. (D) Surface morphology of INPC&LLZO-SCPE via in-situ polymerization. (E) Interpenetrating section of INPC&LLZO-SCPE. (F) Surface of LiFePO4 electrode after in-situ polymerization of monomers. (G) Energy Dispersive Spectrometer elemental distribution of La, Zr, O, and C in INPC&LLZO-SCPE.

The ionic conductivity of the INPC&LLZO-SCPE is related to the LiTFSI and SN contents. For LiTFSI, the content in the polymer ranges from 5 to 50 wt.% with a gradient of 5 wt.%. Supplementary Figure 6A shows the ionic conductivity dependence on the LiTFSI concentration for the composite electrolyte at 25 °C. In the initial stage, the ionic conductivity shows an upward trend with increasing LiTFSI content. When the content of LiTFSI is 30 wt.%, the ionic conductivity reaches a maximum value. After this, the ionic conductivity does not increase and begins to decrease gradually. In addition, SN, as a common additive in ASSLMBs, can be used to deliver an increased amorphous area of the interpenetrating polymer, enhanced movement between the lithium cations and polymer segments, and improved ionic conductivity and interfacial compatibility[15,41,42]. As shown in Supplementary Figure 6B, SN with various contents of 10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 wt.% (mass ratio of SN to polymer) was added to the precursor solution and the ionic conductivity gradually rose with increasing content. Owing to the polymer electrolyte being over-plasticized when the content of SN is 50 wt.%, an optimized value of 40 wt.% was adopted and the corresponding ionic conductivity is calculated to be 2.31 × 10-4 S cm-1. Therefore, the optimized contents of LiTFSI and SN are 16 and 22 wt.% in the INPC&LLZO-SCPE, respectively. Furthermore, it is noteworthy that the polymer electrolyte without the addition of LLZO exhibits the highest ionic conductivity and the best film-forming performance.

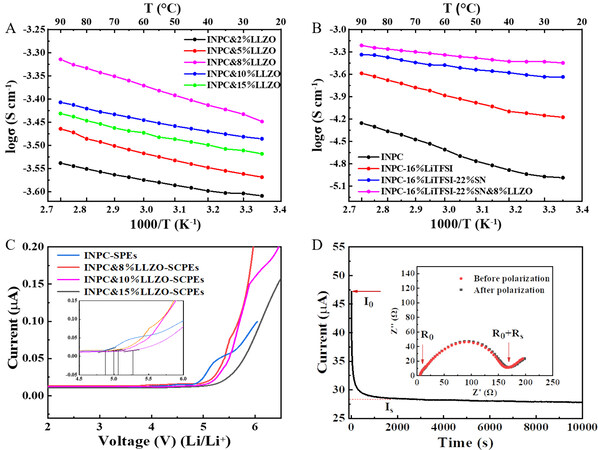

As reported, the inorganic LLZO solid electrolyte with a garnet structure has high ionic conductivity and excellent electrochemical stability and is considered an ideal candidate for ASSLMBs[43-45]. The phase structure of the as-synthesized LLZO was characterized by XRD. As shown in Supplementary Figure 7A, the diffraction patterns of the sample can be well assigned to the cubic garnet phase of LLZO (JCPDS No. 45-0109). There are no impurity peaks present, suggesting a successful synthesis. The SEM image of LLZO particle is shown in Supplementary Figure 7B. The particle size of the active LLZO filler is ~300 nm. LLZO was then used as an inorganic filler and added into the uniform stirred polymer precursor solution with various contents of 2, 5, 8, 10, and 15 wt.% of the polymer. The variation in ionic conductivity is shown in Figure 3A, which shows an increasing trend with increasing content. However, with an increasing LLZO content, undesirable agglomeration will occur, which hinders the migration of Li+ ions and reduces the ionic conductivity of the INPC&LLZO-SCPE. The optimal content of LLZO is 8 wt.%, which corresponds to an ionic conductivity of 3.56 × 10-4 S cm-1.

Figure 3. (A) Ion conductivity of electrolytes with different LLZO contents under various temperatures. (B) Ionic conductivity of electrolytes with different compositions under various temperatures. (C) LSV for different electrolytes at 25 °C. (D) Polarization curve along with the initial and steady-state impedance diagram (inset) for the INPC&LLZO-SCPE at 25 °C.

The ionic conductivity of the electrolytes with different compositions under various temperatures is shown in Figure 3B. With the addition of lithium, SN and LLZO, the ionic conductivity of the polymer electrolyte can be improved. The INPC&LLZO-SCPE has the highest conductivity of 3.56 × 10-4 S cm-1 at room temperature. The electrochemical stability of electrolytes is of major significance for their practical application, which can be evaluated by linear voltammetry. As shown in Figure 3C, a stainless steel/INPC-SPEs/Li battery was assembled and the electrochemical stability window of the polymer electrolyte was measured to be 4.8 V, which is much wider than that of PEO-based batteries. Owing to the polymer electrolyte possessing an individual polycarbonate structure with a high dielectric constant, better electrochemical stability can be obtained. Moreover, benefiting from the introduction of LLZO, the composite electrolyte exhibits a further increase in the electrochemical stability window, even up to 5 V, which is larger than that of pure polymer electrolytes. In addition, the t(Li+) is also vital to the charge and discharge performance of ASSLMBs, and a higher t(Li+) is beneficial for the improvement of the rate capability. According to Equation (2) and Figure 3D, the t(Li+) of the INPC&LLZO-SCPE is calculated to be 0.52, which is larger than that of traditional liquid electrolytes.

SN is commonly used as an additive in electrolytes and can react with the lithium-metal anode and damage the cycling stability[46]. Therefore, to inhibit the interfacial reaction between SN and lithium metal and achieve excellent interfacial stability, lithium metal is always pretreated with FEC to form a SEI film on its surface[47-49]. Supplementary Figure 8 shows the F 1s XPS spectrum of the lithium-metal anode of a cycled Li/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery. Clearly, a strong LiF signal peak can be observed with the Li anode pretreated by FEC [Supplementary Figure 8A]. In contrast, there is only a weak LiF signal peak on the surface of the untreated Li anode, corresponding to the reaction between LiTFSI and lithium metal

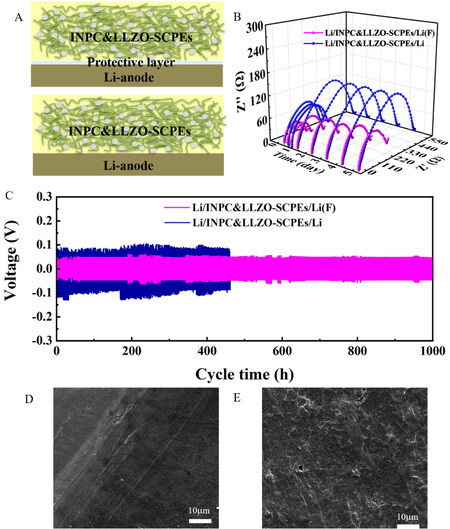

The interfacial stability of the Li/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery was tested by the AC impedance method. Figure 4A shows a schematic of the interfaces between the INPC&LLZO-SCPE films and Li and Li(F) anodes. The interfacial impedance of the lithium-metal symmetrical battery (pretreated by FEC) exhibited no obvious change within 5 d [Figure 4B], illustrating its superior interfacial stability. This result can be explained by the stable SEI film formed on the surface of lithium metal by the FEC treatment, which prevents the reaction between lithium and SN and thus stabilizes the interface. On the contrary, the interfacial stability of the lithium symmetrical battery without the FEC pretreatment is relatively weak, which is associated with the obvious change in resistance on account of the interfacial reaction between SN and Li metal. In addition, the modification of the lithium-metal anode by FEC is also beneficial for the homogeneous lithium plating and band flattening, which can inhibit the growth of lithium dendrites.

Figure 4. (A) Schematic of interfaces between INPC&LLZO-SCPE films and Li and Li(F) anodes. (B) Nyquist plots of the symmetric Li and Li-FEC batteries measured at different storage times at 25 °C. (C) Galvanostatic cycling curves of the symmetric Li-FEC and pristine Li batteries with INPC&LLZO-SCPE at 0.1 mA cm-2. (D) Li-FEC anode after a cycling time of 200 h at 0.1 mA cm-2. (E) Pristine Li anode after a cycling time of 200 h at 0.1 mA cm-2.

The cycling performance of the lithium symmetrical battery is shown in Figure 4C, and the parameters are set to charge for 1 h and discharge for 1 h at 0.1 mA cm-2. The lithium symmetrical battery with the FEC-pretreated Li anode shows enhanced cycling stability for 1000 h without short circuiting. However, the symmetrical lithium battery without the FEC-pretreated Li anode reveals short circuiting after 450 h, which is likely induced by the incomplete lithium dendrite passivation and increased impedance for the accumulation of byproducts. This result is in good agreement with the analysis and testing of the interfacial impedance. Moreover, as shown in Supplementary Figure 9, the cell with Li(F)/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li(F) could run for 400 h at 0.5 mA cm-2. In addition, SEM images of the surface of the Li-metal anode cycled for 200 h at 0.1 mA cm-2 are shown in Figure 4D and E, with the pretreated lithium metal revealing a smooth surface, while obvious lithium dendrites are present on the surface of the untreated sample. Therefore, a stable SEI film was prepared on the surface of the lithium-metal anode through FEC, thereby suppressing the chemical reaction between the lithium-metal anode and SN and improving the cycling stability.

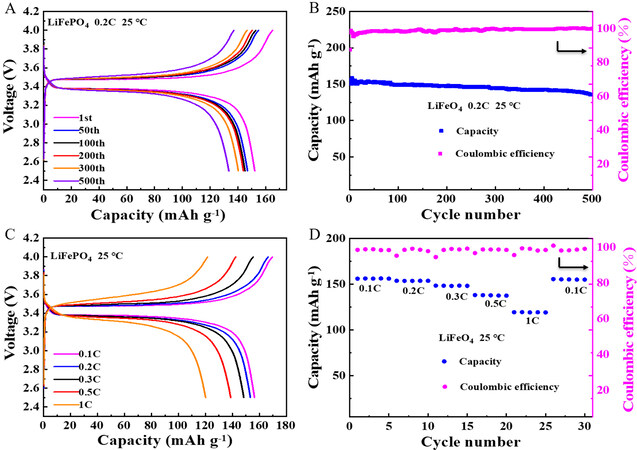

The cycling performance of the LiFePO4/INPC-SPE/Li full battery is shown in Supplementary Figure 10A and B. The initial discharge capacity of the full battery is 148.1 mAh g-1 with a Coulombic efficiency of 79.6%. After 500 cycles, the discharge capacity can remain at 115.6 mAh g-1 with a Coulombic efficiency of 97% and a capacity retention rate of 78.06%. A LiFePO4/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li full battery (the anode is lithium metal pretreated by FEC) was assembled to evaluate the practical application of the composite electrolyte. The charge-discharge curve is collected at 0.2 C with a cut-off voltage of between 2.5 and 4.0 V at 25 °C. As shown in Figure 5A, a steady voltage platform appears at ~3.4 V, which corresponds to the diagnostic redox process of LiFePO4. A flat potential platform with a small overpotential of 0.2 V can be observed, showing a reduced polarization process. The initial discharge capacity of the full battery is 156.3 mAh g-1. Owing to the activation of the cathode and the formation of SEI film, the initial discharge capacity of the battery decreases with increasing cycling. After 500 cycles, the discharge capacity can be retained at 135.6 mAh g-1 with a Coulombic efficiency of 98% and a capacity retention rate of 86.8% [Figure 5B], thereby showing excellent cycling stability. This favorable cycling performance is associated with the high ionic conductivity, preeminent lithium-ion migration number and excellent electrolyte/electrode interfacial compatibility. The charge-discharge curves of the battery at various current densities ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 C are also measured at 25 °C. As shown in Figure 5C, the capacities are 156.1, 153.8, 148.5, 138.2 and 119.4 mAh g-1 at 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5 and 1 C, respectively. The rate capability is shown in Figure 5D and it can be seen that a high discharge capacity of 150 mAh g-1 can be restored even when the current density comes back to 0.1 C, showing the benign rate properties of the battery.

Figure 5. (A) Charge and discharge profiles of LiFePO4/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery after different cycles at 0.2 C and 25 ℃. (B) Cycling stability of LiFePO4/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery at 0.2 C and 25 ℃. (C) Charge and discharge profiles of LiFePO4/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery at various current rates and 25 ℃. (D) Cycling stability of LiFePO4/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery at various current rates at 25 ℃.

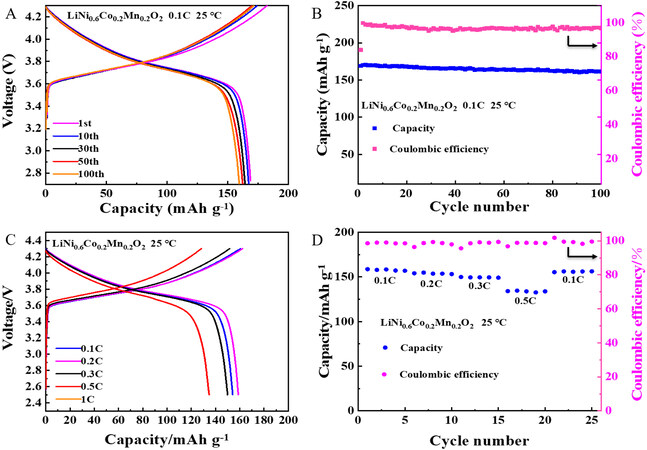

Furthermore, to characterize the high voltage resistance of the composite electrolyte, a LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery was assembled. As shown in Figure 6A-D, the battery delivers a high initial discharge capacity of 158.9 mAh g-1 under 0.1 C at 25 ℃. After 100 cycles, the capacity retention is 93.4%, suggesting a promising potential for the match of the INPC&LLZO-SCPE with the high-voltage cathode material of LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2. In contrast, the cycle performance of the full battery of LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2/INPC-SPE/Li is shown in Supplementary Figure 11A and B. After 100 cycles, the capacity retention rate is 91%.

Figure 6. (A) Charge and discharge profiles of LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery at 0.1 C and 25 ℃. (B) Cycling stability of LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery at 0.1 C and 25 ℃. (C) Charge and discharge profiles of LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery at various current rates and 25 ℃. (D) Cycling stability of LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li battery at various current rates and 25 ℃.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, a novel interpenetrating network polycarbonate-based composite electrolyte (INPC&LLZO-SCPE) was facilely constructed via an in situ polymerization reaction. The process can be divided into 2 steps. First, a polycarbonate monomer with a symmetric structure was synthesized through a nucleophilic substitution reaction method. Second, an in situ polymerization reaction occurs under the existence of an initiator and inorganic filler on the base of the polycarbonate monomer to form the INPC&LLZO-SCPE. By means of the synergistic effect of each component and the unique structure features, the resultant INPC&LLZO-SCPE exhibits high mechanical strength, superior ionic conductivity, an impressive Li+ transference number, and a wide electrochemical window. Furthermore, batteries of LiFePO4/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li and LiNi0.6Co0.2Mn0.2O2/INPC&LLZO-SCPE/Li were assembled to investigate the practical application potential of the composite electrolyte, with considerable electrochemical performance achieved. The creative design of this composite electrolyte paves a new route for the exploration of high-voltage ASSLMBs.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributionsConception of the study and wrote the manuscript: Chen J, Fan L

Material support: Wang C

Data analysis and technical support: Zhou D

Performed experience and data acquisition: Wang G

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipThis work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U21A2080 & 51872027) and Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Z200011).

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2022.

Supplementary MaterialsREFERENCES

2. Bi Z, Guo X. Solidification for solid-state lithium batteries with high energy density and long cycle life. Energy Mater 2022;2:200011.

3. Yang Z, Qin X, Lin K, et al. Realizing ultra-stable SnO2 anodes via in-situ formed confined space for volume expansion. Carbon 2022;187:321-9.

4. Liang J, Luo J, Sun Q, Yang X, Li R, Sun X. Recent progress on solid-state hybrid electrolytes for solid-state lithium batteries. Energy Storage Mater 2019;21:308-34.

5. Wang G, He P, Fan L. Asymmetric polymer electrolyte constructed by metal-organic framework for solid-state, dendrite-free lithium metal battery. Adv Funct Mater 2021;31:2007198.

6. Wu J, Yuan L, Zhang W, Li Z, Xie X, Huang Y. Reducing the thickness of solid-state electrolyte membranes for high-energy lithium batteries. Energy Environ Sci 2021;14:12-36.

8. Famprikis T, Canepa P, Dawson JA, Islam MS, Masquelier C. Fundamentals of inorganic solid-state electrolytes for batteries. Nat Mater 2019;18:1278-91.

9. Bi Z, Huang W, Mu S, Sun W, Zhao N, Guo X. Dual-interface reinforced flexible solid garnet batteries enabled by in-situ solidified gel polymer electrolytes. Nano Energy 2021;90:106498.

10. Tan S, Zeng X, Ma Q, Wu X, Guo Y. Recent advancements in polymer-based composite electrolytes for rechargeable lithium batteries. Electrochem Energ Rev 2018;1:113-38.

11. Ibrahim S, Yassin MM, Ahmad R, Johan MR. Effects of various LiPF6 salt concentrations on PEO-based solid polymer electrolytes. Ionics 2011;17:399-405.

12. Zhou Q, Zhang J, Cui G. Rigid-flexible coupling polymer electrolytes toward high-energy lithium batteries. Macromol Mater Eng 2018;303:1800337.

13. Choudhury S, Stalin S, Vu D, et al. Solid-state polymer electrolytes for high-performance lithium metal batteries. Nat Commun 2019;10:4398.

14. Sun C, Liu J, Gong Y, Wilkinson DP, Zhang J. Recent advances in all-solid-state rechargeable lithium batteries. Nano Energy 2017;33:363-86.

15. Wang C, Wang T, Wang L, et al. Differentiated lithium salt design for multilayered PEO electrolyte enables a high-voltage solid-state lithium metal battery. Adv Sci 2019;6:1901036.

16. Yang X, Jiang M, Gao X, et al. Determining the limiting factor of the electrochemical stability window for PEO-based solid polymer electrolytes: main chain or terminal -OH group? Energy Environ Sci 2020;13:1318-25.

17. Chen L, Li Y, Li S, Fan L, Nan C, Goodenough JB. PEO/garnet composite electrolytes for solid-state lithium batteries: from “ceramic-in-polymer” to “polymer-in-ceramic”. Nano Energy 2018;46:176-84.

18. Zhou D, Shanmukaraj D, Tkacheva A, Armand M, Wang G. Polymer electrolytes for lithium-based batteries: advances and prospects. Chem 2019;5:2326-52.

20. Mindemark J, Lacey MJ, Bowden T, Brandell D. Beyond PEO-Alternative host materials for Li+ -conducting solid polymer electrolytes. Prog Polym Sci 2018;81:114-43.

21. Zhang J, Yang J, Dong T, et al. Aliphatic polycarbonate-based solid-state polymer electrolytes for advanced lithium batteries: advances and perspective. Small 2018;14:e1800821.

22. Xu H, Xie J, Liu Z, Wang J, Deng Y. Carbonyl-coordinating polymers for high-voltage solid-state lithium batteries: solid polymer electrolytes. MRS Energy Sustainability 2020;7:E2.

23. Sun B, Mindemark J, Edström K, Brandell D. Realization of high performance polycarbonate-based Li polymer batteries. Electrochem Commun 2015;52:71-4.

24. Jung YC, Park MS, Kim DH, Ue M, Eftekhari A, Kim DW. Room-temperature performance of poly(ethylene ether carbonate)-based solid polymer electrolytes for all-solid-state lithium batteries. Sci Rep 2017;7:17482.

25. Sun B, Mindemark J, Edström K, Brandell D. Polycarbonate-based solid polymer electrolytes for Li-ion batteries. Solid State Ionics 2014;262:738-42.

26. Liu W, Liu N, Sun J, et al. Ionic conductivity enhancement of polymer electrolytes with ceramic nanowire fillers. Nano Lett 2015;15:2740-5.

27. Fan L, He H, Nan C. Tailoring inorganic-polymer composites for the mass production of solid-state batteries. Nat Rev Mater 2021;6:1003-19.

28. Huo H, Chen Y, Luo J, Yang X, Guo X, Sun X. Rational design of hierarchical “ceramic-in-polymer” and “polymer-in-ceramic” electrolytes for dendrite-free solid-state batteries. Adv Energy Mater 2019;9:1804004.

29. Liu X, Ding G, Zhou X, et al. An interpenetrating network poly(diethylene glycol carbonate)-based polymer electrolyte for solid state lithium batteries. J Mater Chem A 2017;5:11124-30.

30. Zekoll S, Marriner-edwards C, Hekselman AKO, et al. Hybrid electrolytes with 3D bicontinuous ordered ceramic and polymer microchannels for all-solid-state batteries. Energy Environ Sci 2018;11:185-201.

31. Yu X, Wang L, Ma J, Sun X, Zhou X, Cui G. Selectively wetted rigid-flexible coupling polymer electrolyte enabling superior stability and compatibility of high-voltage lithium metal batteries. Adv Energy Mater 2020;10:1903939.

32. Zeng C, Lee LJ. Poly(methyl methacrylate) and polystyrene/clay nanocomposites prepared by in-situ polymerization. Macromolecules 2001;34:4098-103.

33. Lin-gibson S, Bencherif S, Antonucci JM, Jones RL, Horkay F. Synthesis and characterization of poly(ethylene glycol) dimethacrylate hydrogels. Macromol Symp 2005;227:243-54.

34. Nair JR, Destro M, Bella F, Appetecchi GB, Gerbaldi C. Thermally cured semi-interpenetrating electrolyte networks (s-IPN) for safe and aging-resistant secondary lithium polymer batteries. J Power Sources 2016;306:258-67.

35. Zeng XX, Yin YX, Li NW, Du WC, Guo YG, Wan LJ. Reshaping lithium plating/stripping behavior via bifunctional polymer electrolyte for room-temperature solid Li metal batteries. J Am Chem Soc 2016;138:15825-8.

36. Zhang N, Wang G, Feng M, Fan L. In situ generation of a soft-tough asymmetric composite electrolyte for dendrite-free lithium metal batteries. J Mater Chem A 2021;9:4018-25.

38. Oh B, Vissers D, Zhang Z, West R, Tsukamoto H, Amine K. New interpenetrating network type poly(siloxane-g-ethylene oxide) polymer electrolyte for lithium battery. J Power Sources 2003;119-121:442-7.

39. Ju J, Wang Y, Chen B, et al. Integrated interface strategy toward room temperature solid-state lithium batteries. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2018;10:13588-97.

40. Bi Z, Mu S, Zhao N, Sun W, Huang W, Guo X. Cathode supported solid lithium batteries enabling high energy density and stable cyclability. Energy Storage Mater 2021;35:512-9.

41. Zhou D, He Y, Liu R, et al. In situ synthesis of a hierarchical all-solid-state electrolyte based on nitrile materials for high-performance lithium-ion batteries. Adv Energy Mater 2015;5:1500353.

42. Yue L, Ma J, Zhang J, et al. All solid-state polymer electrolytes for high-performance lithium ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater 2016;5:139-64.

43. Du F, Zhao N, Li Y, Chen C, Liu Z, Guo X. All solid state lithium batteries based on lamellar garnet-type ceramic electrolytes. J Power Sources 2015;300:24-8.

44. Jia M, Zhao N, Huo H, Guo X. Comprehensive investigation into garnet electrolytes toward application-oriented solid lithium batteries. Electrochem Energ Rev 2020;3:656-89.

45. Huang W, Zhao N, Bi Z, et al. Can we find solution to eliminate Li penetration through solid garnet electrolytes? Mater Today Nano 2020;10:100075.

46. Alarco PJ, Abu-Lebdeh Y, Abouimrane A, Armand M. The plastic-crystalline phase of succinonitrile as a universal matrix for solid-state ionic conductors. Nat Mater 2004;3:476-81.

47. Zhang X, Cheng X, Chen X, Yan C, Zhang Q. Fluoroethylene carbonate additives to render uniform Li deposits in lithium metal batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2017;27:1605989.

48. Yan C, Cheng X, Tian Y, et al. Lithium metal anodes: dual-layered film protected lithium metal anode to enable dendrite-free lithium deposition (Adv. Mater. 25/2018). Adv Mater 2018;30:1870181.

49. Yang Z, Qin X, Lin K, Cai Q, Fu Y, Li B. Surface passivated Li Si with improved storage stability as a prelithiation reagent in anodes. Electrochem Commun 2022;138:107272.

Cite This Article

Export citation file: BibTeX | RIS

OAE Style

Chen J, Wang C, Wang G, Zhou D, Fan LZ. An interpenetrating network polycarbonate-based composite electrolyte for high-voltage all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Energy Mater 2022;2:200023. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2022.25

AMA Style

Chen J, Wang C, Wang G, Zhou D, Fan LZ. An interpenetrating network polycarbonate-based composite electrolyte for high-voltage all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Energy Materials. 2022; 2(3): 200023. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2022.25

Chicago/Turabian Style

Chen, Jiaxin, Chao Wang, Guoxu Wang, Dan Zhou, Li-Zhen Fan. 2022. "An interpenetrating network polycarbonate-based composite electrolyte for high-voltage all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries" Energy Materials. 2, no.3: 200023. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2022.25

ACS Style

Chen, J.; Wang C.; Wang G.; Zhou D.; Fan L.Z. An interpenetrating network polycarbonate-based composite electrolyte for high-voltage all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Energy Mater. 2022, 2, 200023. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2022.25

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Cite This Article 11 clicks

Cite This Article 11 clicks

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.