An azobenzene-based photothermal energy storage system for co-harvesting photon energy and low-grade ambient heat via a photoinduced crystal-to-liquid transition

Abstract

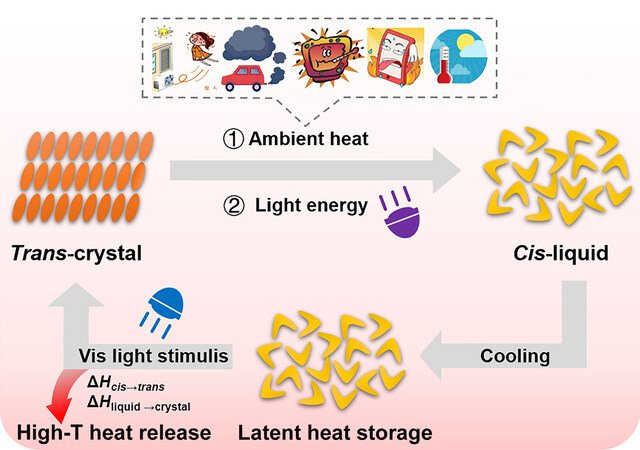

Ambient heat, slightly above or at room temperature, is a ubiquitous and inexhaustible energy source that has typically been ignored due to difficulties in its utilization. Recent evidence suggests that a class of azobenzene (Azo) photoswitches featuring a reversible photoinduced crystal-to-liquid transition could co-harvest photon energy and ambient heat. Thus, a new horizon has been opened for recovering and regenerating low-grade ambient heat. Here, a series of unilateral para-functionalized photoinduced liquefiable Azo derivatives is presented that can co-harvest and convert photon energy and ambient heat into chemical bond energy and latent heat in molecules and eventually release them in the form of high-temperature utilizable heat. A straightforward crystalline-to-liquid phase transition achieved with ultraviolet light irradiation (365 nm) is enabled by appending a halogen/alkoxy group on the para-position of the Azo photoswitches, and the release of thermal energy is triggered by short-wavelength visible-light irradiation (420 nm). The phase transition properties of the trans- and cis-isomers and the energy density, storage lifetime and heat release performance of the cis-liquid are investigated with differential scanning calorimetry, ultraviolet-visible absorption spectroscopy, and an infrared (IR) thermal camera. The experimental results indicate a high energy density of 335 J/g, a long lifetime of 5 d and a heat release of up to

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

Ambient heat, slightly above or at room temperature (RT), is a non-stop and omnipresent energy source that has typically been ignored due to its difficult utilization[1]. Ambient heat sources mainly include thermal radiation from the sun and low-grade waste heat generated by human activities, such as the waste heat from industrial production, the heat produced by refrigeration equipment, and the heat dissipation of electronic devices and vehicle exhausts. These massive amounts of ambient heat cannot yet be collected via economically viable methods, thus causing thermal pollution and resource waste[2-4]. Therefore, technologies that can effectively convert this ambient heat into useful energy are critically needed to achieve its potential in reducing energy consumption and mitigating environmental problems.

Various technologies have been proposed to harvest thermal energy, such as thermoelectrics[4,5], thermochemical[6] and thermophysical[7] approaches, and heat pumps[8]. Phase change heat storage can convert relatively large amounts of ambient heat into latent heat over a very narrow temperature change, making it very suitable for recovering low-grade ambient heat[9-11]. However, phase change materials (PCMs) have an intrinsic limitation, in that the stored heat cannot be released in the form of higher temperatures. Moreover, conventional PCMs present difficulties in controlling the temperatures of heat absorption/release and the heat storage time. With the heat source removed, the ambient temperature drops below the melting or crystallization points and liquefied PCMs can immediately crystallize and lose the latent heat. These uncontrollable processes have constantly challenged long-term latent heat storage in conventional PCMs[12-14]. To date, a physical/chemical solution to gather and convert ambient heat to higher temperatures remains lacking. Thus, it is desirable to develop new technologies or materials to harvest, convert and store ambient heat and eventually release the stored thermal energy controllably.

Most recently, photoliquefiable azobenzene (Azo) molecules have shown significant potential for harvesting and storing thermal energy due to their reversible photoinduced crystal-to-liquid transitions (PCLTs), controllable heat storage and release, and zero gas/chemical emissions[15-19]. Han et al. discovered three heat storage-release schemes for storing thermal energy in liquid-state cis-isomers[20]. It is possible to preserve the latent heat for longer than two weeks in the cis-liquid isomers at temperatures below 0 °C unless triggered by visible light. In a groundbreaking photochemical-thermophysical system, Li and colleagues developed pyrazolylazophenyl ether molecules as solar and heat energy harvesters[21]. The energy capacities of these molecules are believed to be higher than that of conventional solar or heat energy storage methods based purely on phase transition or molecular photoisomerization. Furthermore, Xu et al. reported a novel photochromic dendrimer obtained by grafting Azo units onto dendrimers, which exhibited excellent solar energy storage, controlled heat release, self-repair and controllable adhesive switching properties[22,23]. Moreover, the research group of Han successfully designed new photoliquefiable Azo molecules featuring photocontrolled latent heat storage[24]. Therefore, Azo photoswitches with PCLT capacities have been investigated as promising energy harvest and storage materials. However, research on harvesting and storing ambient heat via PCLTs has not received significant recognition and a photoinduced conversion mechanism of ambient heat into higher temperatures has not been established.

Therefore, we report a series of unilateral para-functionalized photoliquefiable Azo derivatives capable of co-harvesting photon energy and ambient heat and generating high-grade thermal energy. These molecules constitute a solution to recycle and regenerate ambient heat via a photoinduced phase transition, which tactfully couples photochemistry and thermophysics. The unilateral functionalization drastically breaks the symmetry of Azo molecules, leading to a large melting point gap between the trans and cis configurations[20,25]. This molecular asymmetry contributes to cis-liquid phase stability upon cooling until the crystallization and release of heat triggered by specific light. The phase transition properties of trans and cis isomers and the energy density and storage lifetime of cis-liquid form were investigated with ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) absorption spectroscopy and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC). The optically-controlled phase transition is demonstrated by the selective crystallization of cis-liquid films. The heat release performance of the cis-liquid form is monitored using an infrared (IR) thermal camera. Finally, the mechanism by which photon energy triggers the conversion of ambient heat to higher temperatures within the photoliquefiable molecules is discussed. The design principles of the novel energy harvest and storage molecules are also discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL

Reagents and materials

In this study, nitrosobenzene (C6H5NO, 98%), 4-chloroaniline (C6H6ClN, 98%), 4-bromoaniline (C6H6BrN, 99%), 4-iodoaniline (C6H6IN, 98%), para-anisidine (C7H9NO, 99%), 4-ethoxyaniline (C8H11NO, 98%), glacial acetic acid (AR) and a microscope glass slide (24mm × 24mm × 0.17 mm, length × width × thickness) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Dichloromethane (DCM, AR and SP), ethyl acetate (AR) and petroleum ether (AR) were purchased from Tianjin Kemiou Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. All reagents were used directly without further purification.

Synthesis and characterization

Azo compounds were synthesized via the Mills reaction[26,27]. The detailed synthesis procedures and characterization data, including the high-resolution mass spectra (HRMS), 1H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra, and Fourier transform-iIR spectra of the products, are included in Supplementary Table 1.

A SepaBean machine automated flash chromatography system (Santai Technologies, Inc.) was used for purification. 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded using a 400 MHz spectrometer (INOVA, Varian, USA) with chloroform-d as the solvent and tetramethylsilane as an internal standard. IR spectra were recorded using a Bruker Vertex 70 Fourier spectrometer with the powdered samples pressed into KBr pellets. HRMS (ESI) were recorded on a Bruker solanX 70. The samples were charged/discharged under controlled light irradiation with different wavelengths, intensities, and durations. The intensity of light was measured with an optical power meter (CEL-NP2000, Beijing China Education Au-light Co., Ltd.). Optical microscope images were obtained using a Nikon SMZ745T (Japan). An IR thermal imaging camera (Fluke TiX640, USA) was used to monitor the heat released from the samples.

UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy

The UV-Vis absorption spectra (1 cm path-length quartz cuvettes, DCM) were measured using a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (3600 Plus, Shimadzu, Japan). Baselines were corrected and spectra were normalized using Origin8.6 software.

For the solution state test, trans-isomers were dissolved in DCM. The UV-Vis spectra were then recorded as trans-isomers. After that, the samples were irradiated with 365-nm wavelength light (80 mW/cm2) in solution state until they reached a photostationary state (PSS), which generally takes 10 to 30 s. The UV-Vis spectra were then recorded as the cis-isomers. Since the solution-state Azo compounds have ample free space, the cis-isomer content can exceed 95% in the 365-nm PSS. Therefore, we approximate the 365-nm PPS Azo compounds in the solution state as 100% cis-configurations in this work. The UV-Vis absorption spectra of trans- and cis-Azo compounds in solution state (1 × 10-4 mol L-1 DCM solution) can be seen in Supplementary Figures 1, 2A, E and I .

For the solid-state test, a small sample was taken with a glass rod (Φ = 0.5 mm) and dissolved in a cuvette filled with DCM solution. The UV-Vis spectra were then recorded. The obtained data were normalized using Origin 8.6 software. The cis-isomer content in the 365-nm PSS can be estimated as the percentage change of absorbance at the wavelength of the π-π* transition peak following the method reported in the literature[28,29].

%cis ≈ (A – Atrans)/(Acis – Atrans) (1)

The 365-nm PSS in dilute solutions was assumed to be ~100% cis, while the thermal-stationary state was assumed to be ~100% trans. A is the absorbance during the trans-to-cis photoisomerization.

Energy charging process

In a dark room, trans-crystal powder samples were set on a 24 × 24 mm glass slide. The slide was set on a constant temperature heating platform that simulated the ambient heat (T1). The sample was then irradiated with 365-nm wavelength light (80 Mw/cm2, 5 cm away) until the trans-crystal was converted into the cis-liquid through photoisomerization. After that, the heating platform was adjusted to the lowest temperature

DSC measurements

DSC analysis was conducted on a DSC Q20 (TA Instruments, USA) with cooling from an RCS90. If not otherwise stated, the cooling and heating rates were set to 10 °C/min. In the phase transition property experiments, the cis-isomer samples were prepared using the solvent-assisted charging procedure to obtain the values of Tmand Tcas precisely as possible. The specific procedure is as follows. Each trans-isomer was dissolved in DCM and irradiated with 365-nm wavelength light (80 mW/cm2) until reaching the PSS. The solutions were then concentrated and dried in a vacuum before being transferred to DSC pans for analysis. In the energy density measurements experiments, the preparation procedure of the cis-isomer samples was the same as that for the energy charging process.

Lifetime measurements

The cis-liquid samples of the 365-nm PSS were transferred to a dark room at a constant temperature (35 °C for Azo-Cl, 45 °C for Azo-Br, 65 °C for Azo-I and 25 °C for Azo-OMe and Azo-OEt). The UV-Vis absorption spectra of the samples were recorded at regular intervals until the samples reverted to their initial state, i.e., the trans-crystal state. The obtained data were normalized by software.

Photoinduced liquid-to-crystal phase transition experiments

Cis-liquid isomer thin films were prepared by placing 8 mg of trans-crystal isomer sample on a clean glass slide (24 × 24 mm) and melting it on a heating platform. The trans-liquid sample was flattened by pressing with another glass slide to fill the entire space between them and cooled to T1 [Supplementary Table 2] to simulate the ambient heat. The sample was then irradiated with 365-nm wavelength light (80 mW/cm2) to induce the trans-to-cis photoisomerization. The temperature was then reduced to T2 [Supplementary Table 2] using an ethanol bath with a circulatory system and the light irradiation was removed. Half of the sample was covered with cardboard and irradiation was applied with 420-nm wavelength light (80 mW/cm2) to trigger the cis-to-trans isomerization and induce crystallization. After crystallization, the cover was removed and images were taken with an optical microscope at room temperature. The UV-Vis absorption spectra of the samples were recorded at regular intervals during the photoinduced crystallization. The obtained data were normalized by software.

Ir thermal imaging

The cis-liquid samples were set in a dark room at a constant temperature (35 °C for Azo-Cl, 45 °C for Azo-Br, 65 °C for Azo-I and 25 °C for Azo-OMe and Azo-OEt). The samples were then irradiated with 420-nm wavelength light (80 mW/cm2, 5 cm away) under an IR thermal imaging camera.

Theoretical calculations

The structures of molecules 1 to 5 were first optimized using the density functional theory (DFT) at the ωB97XD/def2-SVP level. Among all the possible conformations for both the trans- and cis-isomers, all geometry optimizations were performed using the Gaussian 16a package. Harmonic frequency calculations were performed using the same theory to help verify that none of the structures have imaginary frequencies. The most stable structures were selected to analyze the direction and magnitude of the molecular dipole moment.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Molecular design

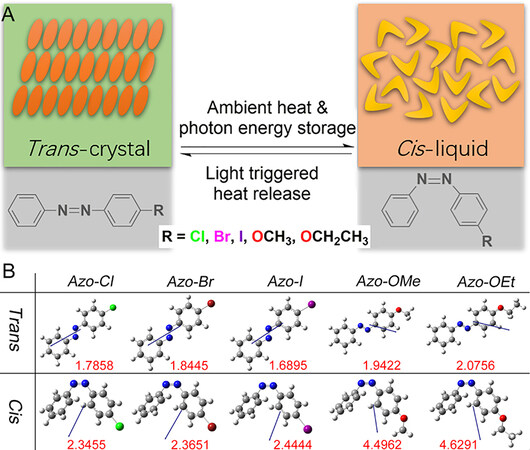

In order to achieve PCLTs, the Azo molecules must have a large melting point gap (ΔTm) between the trans- and cis-isomers so that the trans-crystal and cis-liquid phases can be formed under the specific temperature Tphase(cis-Tm< Tphase< trans-Tm). Grafting functional groups on the benzene ring of the Azo molecules disrupts the molecule symmetry, resulting in a large ΔTmbetween two isomers. In addition, the DFT calculation result shows that the cis isomers of the unilateral-functionalized Azo derivatives have significantly higher polarity than their trans-forms [Figure 1B]. The high polarity of the cis-isomers effectively disrupts the π-π interactions between the aromatic groups, eventually reducing their ability to pack and form ordered crystals.[20] Hence, we synthesized five Azo photoswitches that crystallize in the trans-form and liquefy in the cis-form at or slightly above RT for co-harvesting photon energy and ambient heat via PCLTs [Figure 1A].

Energy charging: photoinduced trans-crystal-to-cis-liquid transition

The photoliquification behaviors of all five Azos forms were observed and presented in Figure 2 and Supplementary Figure 2. To absorb ambient heat above RT, we selected halogen-grafted Azos with photoinduced phase transition temperatures above RT. Such Azos liquify under UV light at ambient temperatures above RT and store the ambient heat in liquid-state molecules as latent heat [Figure 2A, Supplementary Figure 2D and H]. Taking the Azo-Cl molecules as examples, as shown in Figure 2A, an ambient temperature of 60 °C is first simulated. The trans-crystal sample is then irradiated with 365-nm wavelength light to trigger the trans-to-cis photoisomerization and the simultaneous crystal-to-liquid phase transition, which harvests the photon energy and ambient heat. During light irradiation, Azo-Cl was sampled and dissolved, and its isomerization degree was monitored by UV-Vis spectroscopy.

Figure 2. Energy harvested from ambient heat and photons, i.e., the energy charging process. First column: images of Azo-Cl (A) and Azo-OEt (D) samples on glass slides, showing the trans-crystals at the specific temperature, cis-liquid after UV light irradiation (365 nm) and cis-liquid after cooling, as indicated by the arrows. Second column: time-evolved UV-Vis absorption spectra of Azo-Cl (B) and Azo-OEt (E) under UV light of 365 nm. The spectra were normalized with respect to the isosbestic point at 279 nm for Azo-Cl and 302 nm for Azo-OEt, respectively. The arrows indicate the order of tests performed. Third column: the cis-isomer percentage of Azo-Cl (C) and Azo-OEt (F) vs. irradiation time.

For the purpose of maximizing the trans-to-cis photoisomerization and obtaining as much cis-isomer as possible, the cis-liquid sample is cooled to the lowest temperature (T2 in Supplementary Table 2) at which it could remain in the liquid state while maintaining light irradiation. As shown in Figure 2B and C, the

Energy storage

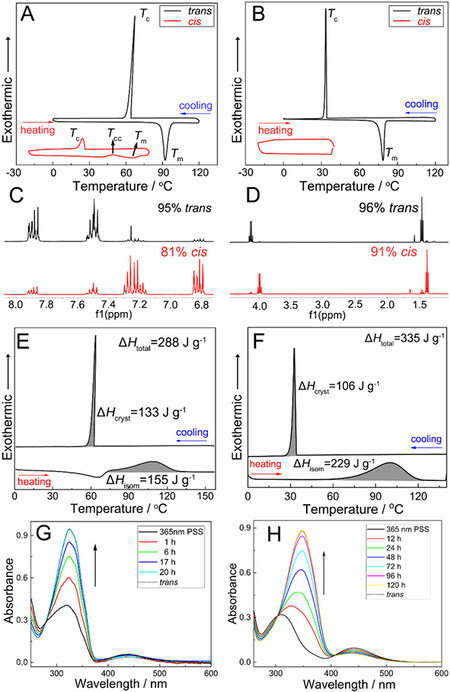

The notable difference in crystallinity between the trans- and cis-isomers of the five as-prepared Azos, i.e., Azo-Cl [Figure 3A], Azo-Br [Supplementary Figure 3A], Azo-I [Supplementary Figure 3B], Azo-OMe

Figure 3. Phase transition of isomers and energy storage properties. First row: DSC plots of trans (top black curve)- and cis (bottom red curve)-isomers upon heating and cooling with Azo-Cl (A) as a representative example of halogen-grafted Azos and Azo-OEt (B) as a representative example of alkoxy-grafted Azos. Tm, Tc, and Tcc represent the melting, crystallization, and cold-crystallization temperatures, respectively. Second row: 1H NMR spectra of Azo-Cl (C) and Azo-OEt (D) isomers for DSC test. Third row: DSC curves of typical cis-liquid Azos for Azo-Cl (E) as a representative example of halogen-grafted Azos and Azo-OEt (F) as a representative example of alkoxy-grafted Azos. Fourth row: time-evolved UV-Vis absorption spectra of the cis-liquid form of Azo-Cl (G) and Azo-OEt (H) reversion in darkness (the spectra were normalized with respect to their corresponding isosbestic point). The arrows indicate the test order.

The cis-forms of the alkoxy-grafted Azos displayed remarkable liquid-phase stability at temperatures below 0 °C, thereby providing opportunities for low-temperature heat release [Figures 3B and Supplementary Figure 3C]. As summarized in Supplementary Table 3, these data match the observed phenomena, suggesting that direct irradiation in the solid state has the same effect on energy storage as the solvent-assisted charging method at RT [Figures 3D and Supplementary Figure 3F]. Therefore, a significant difference can be observed between the trans- and cis-isomers for all Azos. Specifically, the trans-isomers are highly crystalline, while the cis-isomers are liquid at the same temperature. This phase state discrepancy indicates an immense opportunity for co-storing the photon energy and ambient heat in the cis-liquid form of molecules and releasing them as high-grade thermal energy through the cis-liquid-to-trans-crystal transition.

DSC was also used to investigate the amount of energy stored in the cis-liquid isomers of all five Azos: Azo-Cl [Figure 3E], Azo-Br [Supplementary Figure 4A], Azo-I [Supplementary Figure 4B], Azo-OMe

Energy density, storage lifetime and temperature changes of cis-form Azo compounds

| Azo compounds | Energy density | Storage lifetime | Temper-ature changes (°C) | ||||

| Isomerization part | Crystallization part | ΔHtotal (J/g or kJ/mol) | |||||

| Tisom (°C) | ΔHisom (J/g or kJ/mol) | Tc (°C) | ΔHcryst (J/g or kJ/mol) | ||||

| Azo-Cl | 108 | 155 or 34 | 67 | 133 or 29 | 288 or 63 | 20 h | +6 |

| Azo-Br | 107 | 92or 24 | 75 | 97 or 25 | 189 or 49 | 18 h | +5.1 |

| Azo-I | 97 | 102 or 31 | 92 | 70 or 22 | 172 or 53 | 1 h | +4.0 |

| Azo-OMe | 96 | 155 or 33 | 32 | 76 or 18 | 231 or 51 | 5d | +4.7 |

| Azo-OEt | 100 | 229 or 52 | 33 | 106 or 24 | 335 or 76 | 4 d | +6.3 |

Energy discharging: photoinduced cis-liquid-to-trans-crystal transition

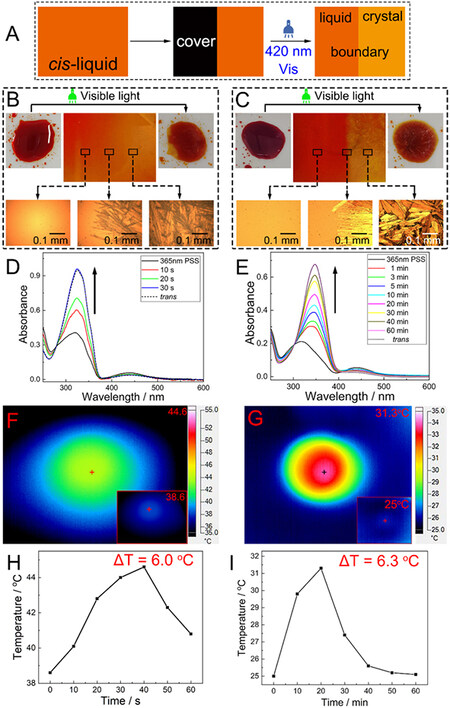

Further verification of the photoinduced crystallization is achieved via selectively exposing the cis-liquid films to visible light (420 nm) using an optical mask (typically cardboard), as shown in Figure 4A. The 420-nm visible light irradiation can help the cis-isomers overcome the energy barrier and accelerate the cis-liquid-to-trans-crystal isomerization. As shown in Figure 4B, C and Supplementary Figure 5A-C, the cis-liquid films are partially covered with cardboard on the left and the entire films are exposed to light irradiation at 420 nm. The phase of the covered part (the left side) has no variation, whereas the right sides of the cis-liquid films crystallize due to light irradiation. These optical microscope images clearly visualize the crystalline features of each trans-isomer and the boundary between the original liquid phase and the generated crystalline phase. This indicates that the crystallization is induced exclusively by light irradiation and not artifact nucleation. Therefore, temporal and spatial control over the heat release can be achieved with light triggers. Supplementary Figure 6 shows the decrease in cis content in the liquid films under the 420-nm wavelength light irradiation. After 20 s of the 420-nm light irradiation, the cis content of the halogen-grafted Azos drops below 40% and crystallizes [Figure 4D, Supplementary Figure 5D and 5E]. In contrast, the alkoxy-grafted Azos require at least 10 min to achieve the same effects [Figure 4E and Supplementary Figure 5F], indicating a higher liquid phase stability.

Figure 4. Experimental demonstration of selective crystallization of liquid sample and the heat release monitoring via photoinduction. (A) Schematic illustration of the selective crystallization of liquid sample via photoinduction. Selective photoinduced crystallization process of (B) Azo-Cl as a representative example of halogen-grafted Azos and (C) Azo-OEt as a representative example of alkoxy-grafted Azos, which were irradiated with visible light (420 nm) at ambient temperatures of 35 and -20 °C, respectively. The left side of the liquid film is covered with cardboard to preserve the cis-isomers in the stable liquid state. Optical microscope images of the left side, right side, and center of the film, indicating cis-isomers at the liquid phase, solid phase, and the liquid and crystalline solid boundary, respectively. The images on the top corners of (B) and (C) depict the cis-liquid samples (left) before and (right) after the 420-nm light irradiation. Normalized UV-Vis spectra of the uncovered parts for (D) Azo-Cl and (E) Azo-OEt during the 420-nm light irradiation. The arrows indicate the test order. IR thermal images of (F) Azo-Cl and (G) Azo-OEt under the 420-nm light irradiation. The insets show the samples before the light irradiation. The number in the upper right corner of each figure indicates the highest temperature of the materials. Temperature-time curves of (H) Azo-Cl and (I) Azo-OEt during heat release. ΔT represents the temperature difference before and after heat release.

For investigating the heat release performance, 420-nm light was used to irradiate the liquid films of the cis-isomers and the temperature changes were observed using an IR thermal imaging camera in real time. As indicated in Figure 4F, G and Supplementary Figure 5G-I, the samples became a source of heat in comparison to their surroundings while under light irradiation. The liquid films exhibited a rapid temperature increase until reaching the highest temperature, indicating that the stored photon energy and ambient heat were completely released. Afterwards, the sample temperature slowly reduced via dissipating heat into the surrounding environment [Figure 4H, I and Supplementary Figure 5J-L]. The temperature changes of the as-obtained Azos are presented in Table 1. Based on these results, it is clear that photoliquefiable Azos have excellent energy-storage capabilities and controlled on-demand heat release, thereby potentially contributing to ambient heat and solar energy utilization.

Mechanism of photoinduced transition between trans-crystal and cis-liquid

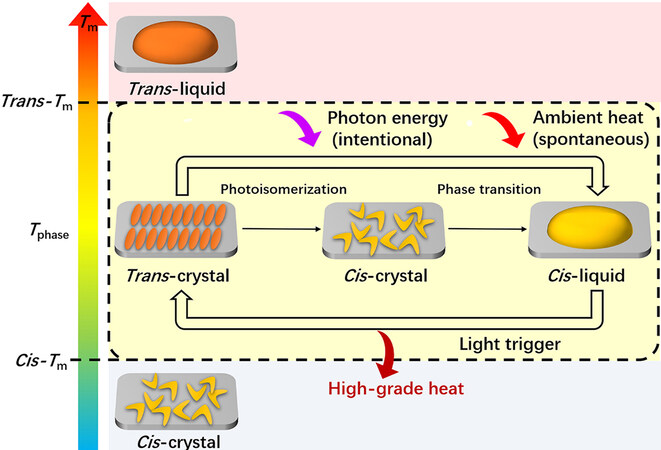

This new energy conversion/storage principle takes advantage of the different melting points of Azo molecules with different configurations, which is a typical PCLT. Figure 5 presents the PCLT mechanism. Generally, the melting point of trans-Azo molecules (trans-Tm) is higher than that of the

Photoinduced ambient heat conversion

We have proved that photoliquefiable Azo molecules can co-harvest and convert photon energy and ambient heat into chemical bond energy and latent heat in molecules, eventually releasing them as utilizable high-grade heat. This new model of renewable energy utilization is illustrated in Figure 6.

From the perspective of thermophysics, conventional PCMs are temperature-dependent and cannot convert ambient heat to a higher temperature. In contrast, photoliquefiable Azo molecules are light-dependent, which can convert ambient heat between two different phase transition temperatures (the high temperature trans-Tm and the low temperature cis-Tm). In the trans-crystal-to-cis-liquid conversion, the phase transition temperature decreased from trans-Tm to cis-Tm alongside the trans-to-cis photoisomerization. Thus, the crystal-to-liquid phase transition occurred at a temperature below trans-Tm, allowing low-grade ambient heat to be harvested. In the cis-liquid-to-trans-crystal conversion, the cis-to-trans isomerization raised the phase transition temperature back (from cis-Tm to trans-Tm), which enabled the crystallization to occur at a temperature above cis-Tm, thus releasing high-grade heat. In short, Azo molecules can liquefy and store thermal energy at cis-Tm but crystallize and release it at trans-Tm. Because trans-Tm is higher than cis-Tm, the heat output can exceed the input. Under such circumstances, designing Azo molecules with a large Tm difference between the trans and cis forms may be the key to such photothermal energy storage systems.

From the perspective of photochemistry, the essence of this hybrid energy system is the photoinduced ambient heat conversion. Whether it is the charging or discharging process, photon energy is indispensable to converting the difficult-to-use ambient heat into utilizable high-grade heat. During the charging process, the additional photon energy induced configuration change of the Azo molecules, thus harvesting or extracting the low-grade heat from the environment and storing them together. During the discharging process, the photon energy enabled the release of the stored energy as high-grade heat. Compared with conventional heat pumps that convert ambient heat by spending high-grade energy (mechanical work or electricity), such photothermal energy storage systems are especially advantageous in terms of sustainability, environmental friendliness, and economics.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, we have developed five photoliquefiable Azo molecules in two categories, namely, halogen-grafted Azos for absorbing ambient heat above RT and alkoxy-grafted Azos for harvesting ambient heat at RT. These Azos can co-harvest photon energy and ambient heat and store them as chemical bond energy and latent heat before releasing them as high-grade heat when needed. This novel photothermal energy harvest and storage system tactfully coupled photochemistry and thermophysics by exploiting the reversible PCLT feature of Azo molecules and achieved photoinduced ambient heat conversion. Unlike traditional molecular solar thermal systems, such a photochemical-thermophysical-coupled mechanism can offer an energy density up to 335 J/g, which is beyond that of systems based purely on phase transition or molecular photoisomerization. The photoinduced selective crystallization of cis-liquid isomers indicated that the heat release was controllable temporally and spatially, which was of great significance for applications requiring heat release on demand. Overall, this work provides a new tactic for recovering and regenerating low-grade ambient heat and paved the way for developing high-energy-density molecular solar thermal systems powered by co-harvesting photon energy and ambient heat. Future investigations may focus on the sunlight-induced trans-crystal-to-cis-liquid transition and photoinduced heat release at temperatures below 0 °C.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributionsconception and design of the study and wrote the manuscript: Dong L

Materials support: Dong L, Wang H, Peng C

Investigation, data analysis and interpretation: Dong L, Zhai F, Feng Y

Reviewed the manuscript, funding acquisition: Feng W

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipThis work was supported by the State Key Program of National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52130303; No. 51633007) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 51973151; No. 51973152; No. 51803151; No. 51773147).

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2022.

Supplementary MaterialsREFERENCES

1. Xu Z, Wang R, Yang C. Perspectives for low-temperature waste heat recovery. Energy 2019;176:1037-43.

2. Gur I, Sawyer K, Prasher R. Engineering. Searching for a better thermal battery. Science 2012;335:1454-5.

3. Cui P, Yu M, Liu Z, Zhu Z, Yang S. Energy, exergy, and economic (3E) analyses and multi-objective optimization of a cascade absorption refrigeration system for low-grade waste heat recovery. Energy Convers Manag 2019;184:249-61.

4. Li T, Zhang X, Lacey SD, et al. Cellulose ionic conductors with high differential thermal voltage for low-grade heat harvesting. Nat Mater 2019;18:608-13.

5. Ying P, He R, Mao J, et al. Towards tellurium-free thermoelectric modules for power generation from low-grade heat. Nat Commun 2021;12:1121.

6. Gerkman MA, Han GG. Toward controlled thermal energy storage and release in organic phase change materials. Joule 2020;4:1621-5.

7. Nazir H, Batool M, Bolivar Osorio FJ, et al. Recent developments in phase change materials for energy storage applications: a review. Int J Heat Mass Transf 2019;129:491-523.

8. Shi G, Aye L, Li D, Du X. Recent advances in direct expansion solar assisted heat pump systems: a review. Renew Sust Energy Rev 2019;109:349-66.

9. da Cunha J, Eames P. Thermal energy storage for low and medium temperature applications using phase change materials - a review. Appl Energy 2016;177:227-38.

10. Chen X, Cheng P, Tang Z, Xu X, Gao H, Wang G. Carbon-based composite phase change materials for thermal energy storage, transfer, and conversion. Adv Sci 2021;8:2001274.

11. Chen X, Tang Z, Liu P, Gao H, Chang Y, Wang G. Smart utilization of multifunctional metal oxides in phase change materials. Matter 2020;3:708-41.

12. Lu Y, Yu D, Dong H, et al. Magnetically tightened form-stable phase change materials with modular assembly and geometric conformality features. Nat Commun 2022;13:1397.

13. Kashyap V, Sakunkaewkasem S, Jafari P, et al. Full spectrum solar thermal energy harvesting and storage by a molecular and phase-change hybrid material. Joule 2019;3:3100-11.

14. Tang Z, Gao H, Chen X, Zhang Y, Li A, Wang G. Advanced multifunctional composite phase change materials based on photo-responsive materials. Nano Energy 2021;80:105454.

15. Xu WC, Sun S, Wu S. Photoinduced reversible solid-to-liquid transitions for photoswitchable materials. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl 2019;58:9712-40.

16. Qiu Q, Shi Y, Han GGD. Solar energy conversion and storage by photoswitchable organic materials in solution, liquid, solid, and changing phases. J Mater Chem C 2021;9:11444-63.

17. Fei L, Yin Y, Yang M, Zhang S, Wang C. Wearable solar energy management based on visible solar thermal energy storage for full solar spectrum utilization. Energy Stor Mater 2021;42:636-44.

18. Xu X, Wang G. Molecular solar thermal systems towards phase change and visible light photon energy storage. Small 2022;18:e2107473.

19. Hu J, Huang S, Yu M, Yu H. Flexible solar thermal fuel devices: composites of fabric and a photoliquefiable azobenzene derivative. Adv Energy Mater 2019;9:1901363.

20. Gerkman MA, Gibson RSL, Calbo J, Shi Y, Fuchter MJ, Han GGD. Arylazopyrazoles for long-term thermal energy storage and optically triggered heat release below 0 °C. J Am Chem Soc 2020;142:8688-95.

21. Zhang ZY, He Y, Wang Z, et al. Photochemical phase transitions enable coharvesting of photon energy and ambient heat for energetic molecular solar thermal batteries that upgrade thermal energy. J Am Chem Soc 2020;142:12256-64.

22. Xu X, Zhang P, Wu B, et al. Photochromic dendrimers for photoswitched solid-to-liquid transitions and solar thermal fuels. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2020;12:50135-42.

23. Xu X, Wu B, Zhang P, et al. Arylazopyrazole-based dendrimer solar thermal fuels: stable visible light storage and controllable heat release. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2021;13:22655-63.

24. Shi Y, Gerkman MA, Qiu Q, Zhang S, Han GGD. Sunlight-activated phase change materials for controlled heat storage and triggered release. J Mater Chem A 2021;9:9798-808.

25. Qiu Q, Gerkman MA, Shi Y, Han GGD. Design of phase-transition molecular solar thermal energy storage compounds: compact molecules with high energy densities. Chem Commun 2021;57:9458-61.

26. Volgraf M, Gorostiza P, Szobota S, Helix MR, Isacoff EY, Trauner D. Reversibly caged glutamate: a photochromic agonist of ionotropic glutamate receptors. J Am Chem Soc 2007;129:260-1.

27. Bellotto S, Reuter R, Heinis C, Wegner HA. Synthesis and photochemical properties of oligo-ortho-azobenzenes. J Org Chem 2011;76:9826-34.

28. Victor JG, Torkelson JM. On measuring the distribution of local free volume in glassy polymers by photochromic and fluorescence techniques. Macromolecules 1987;20:2241-50.

29. Saydjari AK, Weis P, Wu S. Spanning the solar spectrum: azopolymer solar thermal fuels for simultaneous UV and visible light storage. Adv Energy Mater 2017;7:1601622.

30. Weis P, Hess A, Kircher G, et al. Effects of spacers on photoinduced reversible solid-to-liquid transitions of azobenzene-containing polymers. Chemistry 2019;25:10946-53.

31. Chen M, Yao B, Kappl M, et al. Entangled azobenzene-containing polymers with photoinduced reversible solid-to-liquid transitions for healable and reprocessable photoactuators. Adv Funct Mater 2019;30:1906752.

Cite This Article

Export citation file: BibTeX | RIS

OAE Style

Dong L, Zhai F, Wang H, Peng C, Feng Y, Feng W. An azobenzene-based photothermal energy storage system for co-harvesting photon energy and low-grade ambient heat via a photoinduced crystal-to-liquid transition. Energy Mater 2022;2:200025. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2022.26

AMA Style

Dong L, Zhai F, Wang H, Peng C, Feng Y, Feng W. An azobenzene-based photothermal energy storage system for co-harvesting photon energy and low-grade ambient heat via a photoinduced crystal-to-liquid transition. Energy Materials. 2022; 2(4): 200025. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2022.26

Chicago/Turabian Style

Dong, Liqi, Fei Zhai, Hui Wang, Cong Peng, Yiyu Feng, Wei Feng. 2022. "An azobenzene-based photothermal energy storage system for co-harvesting photon energy and low-grade ambient heat via a photoinduced crystal-to-liquid transition" Energy Materials. 2, no.4: 200025. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2022.26

ACS Style

Dong, L.; Zhai F.; Wang H.; Peng C.; Feng Y.; Feng W. An azobenzene-based photothermal energy storage system for co-harvesting photon energy and low-grade ambient heat via a photoinduced crystal-to-liquid transition. Energy Mater. 2022, 2, 200025. http://dx.doi.org/10.20517/energymater.2022.26

About This Article

Copyright

Data & Comments

Data

Cite This Article 23 clicks

Cite This Article 23 clicks

Comments

Comments must be written in English. Spam, offensive content, impersonation, and private information will not be permitted. If any comment is reported and identified as inappropriate content by OAE staff, the comment will be removed without notice. If you have any queries or need any help, please contact us at support@oaepublish.com.