Insights into the electrochemical performance of metal fluoride cathodes for lithium batteries

Abstract

In recent years, energy storage and conversion have become key areas of research to address social and environmental issues, as well as practical applications, such as increasing the storage capacity of portable electronic storage devices. However, current commercial lithium-ion batteries suffer from low specific energy and high cost and toxicity. Conversion-type cathode materials are promising candidates for next-generation Li metal and Li-ion batteries (LIBs). Metal fluoride materials have shown tremendous chemical tailorability and exhibit excellent energy density in LIBs. Batteries based on such electrodes can compete with other envisaged alternatives, such as Li-air and Li-S systems. However, conversion reactions are typically multiphase redox reactions with mass transport phenomena and nucleation and growth processes of new phases along with interfacial reactions. Therefore, these reactions involve nonequilibrium reaction pathways and significant overpotentials during the charge-discharge process. In this review, we summarize the key challenges facing metal fluoride cathode materials and general strategies to overcome them in cells. Different synthesis methods of metal fluorides are also presented and discussed in the context of their application as cathode materials in Li and LIBs. Finally, the current challenges and future opportunities of metal fluorides as electrode materials are emphasized. With continuous rapid improvements in the electrochemical performance of metal fluorides, it is believed that these materials will be used extensively for energy storage in Li batteries in the future.

Keywords

INTRODUCTION

The story of Li batteries started in the 1950s when lithium metal was used as an anode material in non-aqueous primary cells[1-5]. The high energy densities and low chemical potential of Li/Li+ (-3.04 V vs. SHE) make Li batteries the most favorable devices for energy storage. Later, in 1977-1979, coin cells based on a TiS2 cathode, Li-alloy anode, and organic electrolyte (LiClO4-dioxolane) were successfully commercialized by Exxon[5], followed by comprehensive research on a series of Li-free cathode materials, including TaS2, MoS2, TiS2, VS2, NbS2 and CrS2[5,6]. Unfortunately, secondary batteries with Li metal anode carry a risk of explosion due to the growth of lithium dendrites that can pierce the separator during cycling. To solve this problem, the Li-metal anode was replaced by a carbon anode to assemble powerful and safe Li-ion batteries (LIBs). Presently, the fast-growing market requires next-generation rechargeable Li and LIBs to charge faster, have higher energy density and be cheaper and safer. Battery materials with high capacity are therefore being largely developed and explored in advanced LIBs. Unfortunately, many of the cathode materials, like lithium cobalt oxide, lithium nickel oxide, and LiMn2O4, used nowadays for traditional LIBs have limits in electrochemistry, such as low energy density, safety hazards, high price, and environmental issues. Recently, owing to the progress in solid electrolyte research, Li-metal batteries are expected to make a comeback[3,7-9] as the anode material is based on metal Li, and it is therefore not essential for the cathode to contain Li.

Efforts to prepare Li-free cathodes have increased in recent years because of the perspective advantages of Li-free cathode materials, such as eco-friendliness, low cost, and high capacity. As one type of Li-free cathode material, conversion-type metal fluoride cathodes, which exhibit low cost and high theoretical capacity, have recently attracted substantial attention[10]. Mainly, Li-S battery systems have been widely considered, but S cathodes still face several issues, such as the dissolution of intermediate lithium polysulfides in the electrolyte and low volumetric energy density[11,12]. The high ionicity of the M-F bond favors a higher reaction voltage compared to their oxide and sulfide counterparts[13]. Therefore, metal fluoride-based cathodes (e.g., NiF2, FeF2, FeF3 and so on) hold significant promise for energy storage applications[14-17].

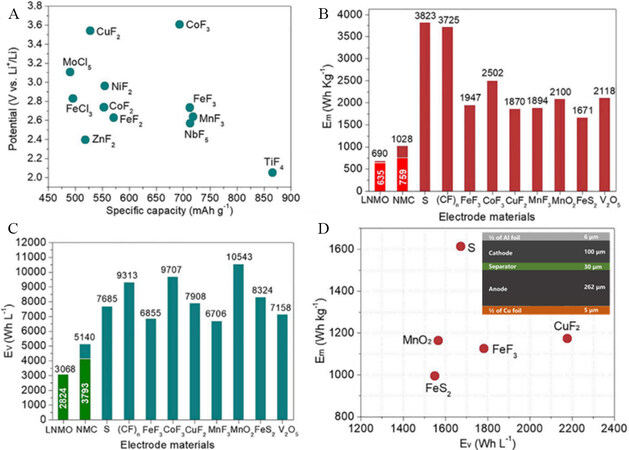

Figure 1A shows the theoretical specific capacities and operational voltages for Li-free cathodes[3]. It is found that metal fluorides have the highest electromotive force due to the high electronegativity of F. Metal fluoride cathodes also show high gravimetric (> 1600 Wh kg-1) and volumetric (> 6700 Wh L-1) energy densities [Figure 1B and C] compared to LIBs cathodes, such as LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 and sulfur. Figure 1D shows the cell energy densities of transition metal fluorides, with values of 1172 Wh kg-1 (2178 Wh L-1) for CuF2 and 1125 Wh kg-1 (1782 Wh L-1) for FeF3. It is noteworthy that the real energy densities will decrease because a higher percentage of carbon and solid-state electrolytes need to be mixed with the cathodes and anodes to improve the ionic and electron conductivity and achieve better battery performance. Nevertheless, it still remains much higher than that of current LIBs (150-300 Wh kg-1).

Figure 1. (A) Theoretical specific capacity and operational voltage for conversion cathodes. (B) and (C) Gravimetric and volumetric energy densities of Li-free cathodes (LiNi0.5Mn1.5O4 denoted as LNMO and Li(NiMnCo)1/3O2 denoted as NMC). (D) Energy density of solid-state Li batteries with different cathodes: FeF3; CuF2; MnO2; S (inset shows a schematic of a solid-state battery). Reproduced from Ref.[3] with permission. Copyright 2019 Elsevier Inc.

Recently, Na- and K-ion batteries are becoming more promising for large scale energy-storage, which can alleviate the concerns regarding the scarcity of Li resources. Although the well-established LIB technology can be exploited for them, their energy density is generally lower than that of LIBs. Therefore, developing high-performance electrode materials is also one of the research emphases for Na- and K-ion batteries. Metal fluorides (FeF2, FeF3 and CuF2) exhibit promising electrochemical performance, which could be the solution for batteries in the future.

In this review, we summarize the key challenges facing metal fluoride cathode materials and general strategies to overcome them in cells. Different synthesis methods for these materials are described and their electrochemical applications as cathode materials in Li batteries and LIBs are discussed. Finally, the current challenges and future opportunities of metal fluorides as electrode materials are emphasized. We provide a conclusive review of the recent progress made for the rational design of metal fluoride cathode materials in electrochemistry for energy storage in Li batteries.

CONVERSION REACTION MECHANISM IN METAL FLUORIDE CATHODES

As one of the reaction pathways for batteries, conversion reactions involve the reduction of the active material into metallic nanoparticles and the formation of a Li compound, which is different from intercalation and alloying reactions. The generalized reaction formula can be expressed as:

MaXb + (b · n)Li = aM + bLinX (M = metal; X = O, S, F or P) (1)

It should be noticed that an alloying reaction can take place when M is electrochemically active with Li (e.g., Sn, Sb or Zn), but this is beyond the scope of this review. Conversion-type electrode materials can usually achieve high reversible capacity because the specific capacity can be increased by using metal compounds with high oxidation states. In addition, the working potential of these materials can be easily controlled by tuning the ionicity of the M-X bond.

In 1997, FeF3 was first introduced as a prospective insertion-type LIB cathode material with a high theoretical energy density (237 mAh g-1) based on a one-electron transfer and high discharge platform (average of 3 V). This opens up potential opportunities for next-generation LIBs[18]. Three decades later, the physical proof and stability of the metal fluoride conversion electrode have been separately demonstrated[19,20]. The past decade has witnessed tremendous advances in the preparation of metal fluoride electrode materials with improving electrochemical performance. The electrochemical performance, morphology, and particle size of some of the recent metal fluoride cathode nanomaterials are summarized in Table 1.

Electrochemical performance of metal fluoride cathode materials for LIBs

| Electrode materials | Morphology | Particle size (nm) | Specific capacity (mAh g–1) | Cycle number | Ref./Year |

| FeF3 | layer hexagonal | - | 80 | - | [18] 1997 |

| TiF3 | layer hexagonal | - | 80 | - | |

| VF3 | layer hexagonal | - | 80 | - | |

| MnF3 | layer hexagonal | - | 80 | - | |

| FeF3 | Film | 200-300 | 571.2 | 30 | [21] 2006 |

| NiF2 | Nanoparticles | 20-30 | 540 | 35 | [22] 2008 |

| FeF3·0.33H2O | sponge-like | 10 | 712 | 35 | [23] 2010 |

| Li3FeF6 | prismatic particles | 50 | 100 | - | [24] 2010 |

| FeF3·0.33H2O | hierarchy | 11 | 115 | 50 | [25] 2011 |

| CuF2 | Thin film | 200 | 424 | 45 | [26] 2011 |

| FeF2 | Nanoparticles | < 5 | [27] 2011 | ||

| CuF2 | 5-12 | ||||

| FeF2 | Nanoparticles | 9.1 | [28] 2012 | ||

| FeF3 | Nanoparticles | 600 | [29] 2012 | ||

| FeF3 | Nanoparticles | 5 | ~200 | 80 | [30] 2012 |

| FeF3 | Nanoparticles | 55 | 140 | 50 | [14] 2013 |

| FeF3·0.5H2O | Nanoparticles | 10 | 115 | 100 | [31] 2013 |

| FeF3 | Nanospheres | 70-100 | 222 | 50 | [32] 2013 |

| FeF3·0.33H2O | Nanoparticles | 10 | 140 | 100 | [33] 2013 |

| FeF2 | Films | 850 | 511 | 10 | [34] 2014 |

| FeF2.2(OH)0.8·(H2O)0.33 | hexagonal-shaped particles | 750 | 110 | 40 | [35]2014 |

| FeF3·0.33H2O | Cylindrical | 1000-2000 | 137 | 100 | [36] 2014 |

| FeF3·0.33H2O | Nanopetal | 123 | 50 | [37] 2014 | |

| FeF3 | Particles | > 200 | 50 | [38] 2014 | |

| Fe1.9F4.75·0.95H2O | Nanorods | 148 | 100 | [39] 2014 | |

| FeF3 | Nanocrystals | 30 | 200 | [40] 2014 | |

| CuF2 | [41] 2014 | ||||

| FeF3 | Powders | 230 | 60 | [42] 2015 | |

| LiF/FeF3 | Nanoparticles | 260.1 | [43] 2015 | ||

| FeF3·0.33H2O | Nanopetals | 15 | 145 | 30 | [44] 2015 |

| MoF3 | [45] 2015 | ||||

| FeF3 | Powder | 237 | 30 | [46] 2015 | |

| Β-FeF3·3H2O | Nanoparticles | 146.5 | 10 | [47] 2015 | |

| FeF3 | [48] 2016 | ||||

| FeF3 | Nanoparticles | 423 | [49] 2016 | ||

| MnF2 | Nanoparticles | 50-200 | 489 | 100 | [50] 2016 |

| HTB-FeF3 | 200-450 | 100 | [51]2016 | ||

| FeF3·0.33H2O | 250 | [52] 2016 | |||

| MnF2 | Nanorods | 420 | 2000 | [53] 2016 | |

| FeF3 | fusiform structure | 137.3 | 100 | [54] 2017 | |

| FeF3 | nanocrystals | 93.8 | 500 | [55] 2017 | |

| FeF3·3H2O | Flower-like | 172.3 | 50 | [56] 2017 | |

| CuF2 | [57] 2017 | ||||

| FeF3 | Nanocrystal | 5-20 | 155 | 100 | [58] 2017 |

| CoF3 | Nanopowder | 390 | 14 | [59] 2017 | |

| CuF2 | Nanostructures | 270 | [60] 2017 | ||

| Li2NiF4 | Nanospheres | 548 | 40 | [61] 2017 | |

| FeF3 | Nanosheets | [62] 2018 | |||

| FeF3·0.33H2O | Hierarchical | [63] 2018 | |||

| FeF3 | [64] 2018 | ||||

| CoF3 | 550 | [65] 2018 | |||

| FeOF | Cubic | [66] 2018 | |||

| CuF2 | Nanoparticles | 30-70 | [67] 2018 | ||

| LiF/Fe/Cu | 375-400 | 200 | [68] 2019 | ||

| CuF2 | [69] 2019 | ||||

| FeF2.2(OH) 0.8 | [70] 2019 | ||||

| FeF2 | [71] 2019 | ||||

| FeF3·0.33H2O | Microspheres | 172 | [72] 2019 | ||

| MnF2 | Nanolayer | 296.8 | 100 | [73] 2019 | |

| FeF3·0.33 H2O | Nanoparticles | 190 | 50 | [74] 2019 | |

| FeF3·0.33H2O | Raspberry-like | 284 | 100 | [75] 2020 |

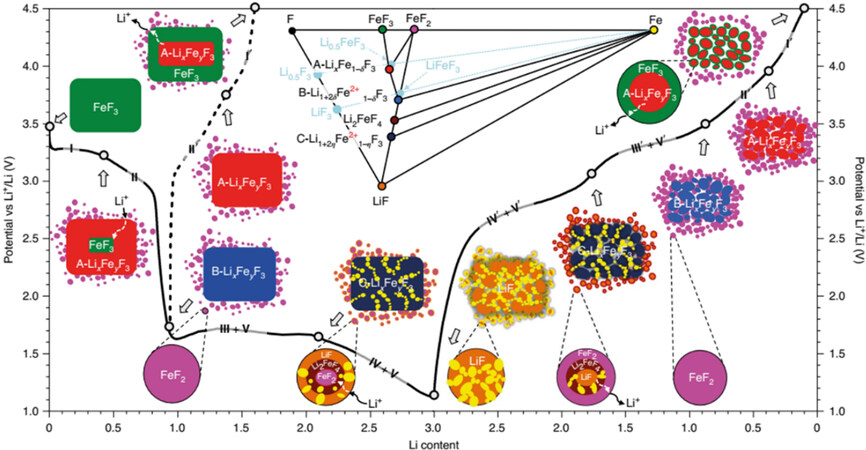

Among all the metal fluoride phases, FeF3 cathodes with the multielectron transfer mechanism have received the most attention because of their high energy density and low cost. This material converts to nanocomposites of metal nanoparticles dispersed in a LiF matrix during the conversion reaction. Metallic iron may be nucleated to form nanosized Fe particles at the same initial atomic sites in the old phase, while newly formed LiF occupies the space around the metallic iron nanoparticles on the other side during lithiation. The diffusion coefficients of the anions and cations, the ionic and electronic conductivities of the new phase and the interfacial energies can be used to control the morphology of these cathode materials. Numerous studies have correlated the phase behavior in the insertion regime with reaction kinetics but with different mechanisms. The majority of studies indicate that the ReO3 structure comprising corner-sharing FeF6 groups transforms into the trirutile LixFeF3 phase with an edge-sharing structure. There is a transformation that involves a considerable change in the Fe ordering and anion packing, albeit with different x values. Recently, Hua et al. revealed that FeF3 lithiation is mainly a diffusion-controlled substitution mechanism. Furthermore, there is a clear topological relationship between the metal fluoride and F− sublattices to that of LiF[7], as shown in Figure 2. FeF2 is formed on the particle surface during the initial lithiation of FeF3. The A-LixFeyF3 phase (cation ordered and stacking disordered) is then formed along with FeF2. This structure is related with α-/β-LiMn2+Fe3+F6 and can topotactically transform to B- and then C-LixFeyF3 before forming LiF and Fe.

Figure 2. Reaction pathways of FeF3-FeF2 cathode. The reference phases in the phase diagram are indicated by light blue circles to show the positions of A- and B-LixFeyF3, whose Fe concentration is off-stoichiometric. Reproduced from Ref.[7] with permission. Copyright 2021 Springer Nature.

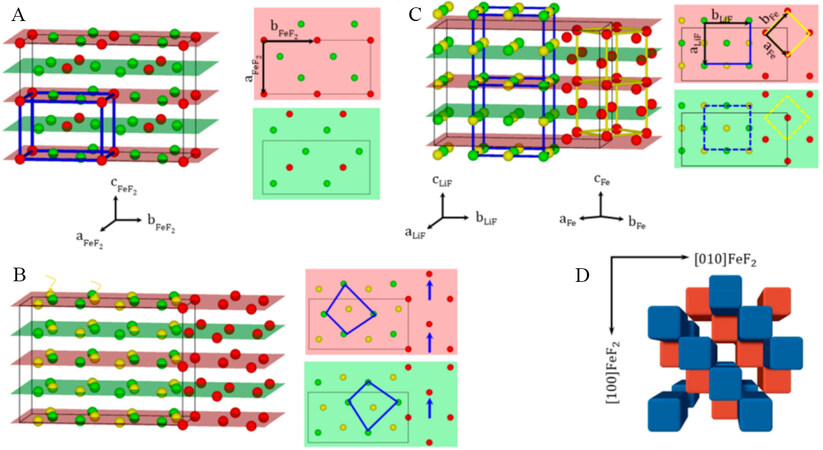

Iron fluoride (FeF2) has also been widely studied as a model system for mechanistic studies. However, the lithiation of FeF2 involves the formation of nanosized reaction products (LiF and Fe) and many possible intermediate phases. Karki et al. studied the conversion reactions in a single crystal of FeF2. They reported a lithiation-driven topotactic transformation between the parent and converted phases by in situ visualization of the spatial and crystallographic correlation[9]. Specifically, conversion in FeF2 cathode involves the transport of both Fe2+ and Li+ ions within the F- array and leads to the formation of nanosized Fe along specific crystallographic orientations of FeF2, as shown in Figure 3. During the whole process, the retained F-anion framework creates a checkerboard-like structure, which can compensate the large volume change and thereby enable high cyclability in FeF2.

Figure 3. (A) Schematic illustration of structure of FeF2 with Fe (red) and F (green). In the 3D view (left), the unit cell is outlined by thick blue lines. The thin black lines outline a 1 × 2 × 2 supercell. Alternative arrangement of Fe-F along the [001] direction in the unit cell is shown in the red and green planes. (B) Li (yellow) insertion along the [001] direction. (C) Expansion/contraction of Fe/LiF along different directions. (D) Perspective view of checkerboard arrangement of the converted Fe domains along the [001] FeF2 direction. Reproduced from Ref.[9] with permission. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

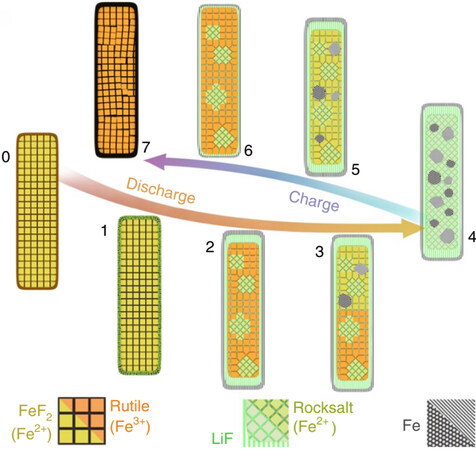

Xiao et al. prepared single-crystalline, monodisperse FeF2 nanorods through colloidal synthesis[8]. The nanorods presented near a theoretical capacity of 570 mA h g-1 and good cycling stability, solely through the use of an ionic liquid electrolyte (1 M LiFSI/Pyr1,3FSI). In this work, the conversion mechanism detailed reveals that the discharge and charge reactions are controlled by different mechanisms. As shown in Figure 4, the charge process is an interface-controlled reaction with the slow diffusion of Fe2+ through a rock-salt lattice. This is one of the main causes of inherently sluggish of voltage. In contrast, the discharge process is a diffusion-controlled reaction with the fast diffusion of Fe0 through open channels. The study suggests that voltage hysteresis is primarily a result of the reaction overpotential because the charge and discharge pathways are spatially and chemically symmetric. Based on the above results, we can mitigate the reaction hysteresis potentially through materials design. For example, a conductive bridge for electron transport can be made by doping or structural control to provide an enormous interface among nanosized products for the reversible conversion reaction. Regardless of the theoretical significant features of metal fluoride materials, many challenges still need to be resolved before these materials can achieve their desired performance characteristics. These challenges include low ionic and electron conductivities, voltage hysteresis, and unfavorable side reactions between active materials and electrolytes, all of which may lead to poor electrochemical performance and low Coulombic efficiency and energy efficiency.

Figure 4. Schematic illustration of full discharge-charge mechanism for FeF2 electrode. (1) Forming disordered Fe and LiF at the surface. (2) Forming trirutile and rocksalt phases throughout the interior accompanied by formation of Fe and LiF particles with double-layered shell. (3) The shell limits the propagation of the reaction to the [001], creating a boundary between the converted (iron containing) and unconverted regions. (4) Fully discharged state with Fe nanoparticles nucleated on the fluoride matrix. (5) Charging proceeds with the consumption of these Fe nanoparticles. (6) This is followed by the reconversion of the double-layered shell and the re-formation of a pseudo-single-crystalline rutile nanorod. Reproduced from Ref.[8] with permission. Copyright 2021 Springer Nature.

LIMITATIONS OF CONVERSION MATERIALS AND STRATEGIES TO OVERCOME THEM

Low conductivity

Metal fluoride (FeF3 and FeF2)-based cathode materials are particularly promising materials due to their high volumetric and gravimetric capacities[17]. However, the strong ionic bond between M and F results in a large band gap, which makes metal fluoride materials poor electronic conductors[76,77]. The large interfacial energy of Fe/LiF enhances the mass transport resistance, which hinders the development of large metals and LiF clusters during the cycling process. Furthermore, the harsh interactions between the electrolyte and metal fluoride cathode additionally improve the cell resistance and contribute to Fe degradation and dissolution, thus leading to rapid capacity fading upon cycling and irreversible structural changes along with low rate capability[19]. In addition, the slow separation of the Fe and LiF phases during the cycling process may lead to capacity fading and cell polarization growth[27]. To overcome some of these problems, the development of various metal fluoride-based nanocomposites has been significantly explored[78,79]. Various conductive carbons, including graphene, carbon blacks, carbon fibers, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and micro- and mesoporous carbons, have been greatly explored in such hybrid composite cathode syntheses and exhibited noticeable improvements in battery performance[17,80,81]. The poor electronic conduction of the electrode can be improved by the introduction of highly conductive materials, e.g., carbon and metal/metal oxides, which is effective in overcoming this limitation and positively improving the reversible capacity and stability of metal fluoride electrodes. The conductive species with an electron transport chain introduced into the active core material can maintain good electronic contact and effectively improve the kinetic behavior. Furthermore, the coating or adhesion of the external moieties on the active material surface efficiently hinders the side reaction and overpowers the dissolution.

Carbon-based metal fluoride nanocomposites

To improve the electrochemical performance and cycle stability, carbon-based nanocomposites have been used successfully because of their unique properties, such as high structural stability, high electronic conduction, large pore volume, and high surface area. Consequently, carbon composites with nanocomposites as core materials exhibit excellent electrochemical performance. Time, t, is proportional to the square of the diffusion length, L, during Li-ion diffusion, as shown in Equation (2)[82-84]:

t = L2/D (2)

where D is the diffusion coefficient of Li ions.

The Badway group first reported carbon and metal fluoride nanocomposites (CMFNCs) as reversible cathodes to improve the electrochemical efficiency of metal fluorides[85]. They synthesized the CMFNCs via a ball-milling method, which showed a reversible specific capacity of ~600 mAh g-1 with a discharge voltage from 4.5 to 1.5 V. This result arises from the fact that the surface of nanosized crystals contains a number of surface defects that contribute significantly to improve the ionic and electronic activity. Nearly a third of the discharge capacity progressed in a cathode reduction reaction of Fe3+ to Fe2+ between 3.5 and 2.8 V, while the remaining specific capacity was provided by a two-phase conversion reaction at ~2 V, forming a finer Fe/LiF nanocomposite. Furthermore, the preliminary results of CoF2, NiF2, and FeF2 CMFNCs were also used for comparison in the discussion of the electrochemical performance of the metal fluoride-based conversion reaction.

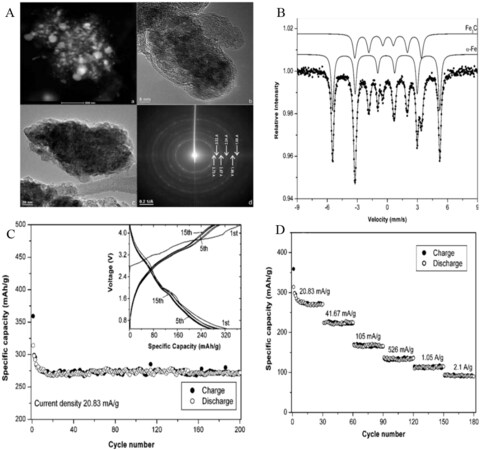

Despite intensive efforts, the poor cycling stability and partial reaction irreversibility have largely hampered the application of metal fluoride cathodes[18,19,86-88]. Therefore, an alternative method for the synthesis of cathode materials is desirable. For this reason, the intercalation of metal fluorides into a carbon matrix might be an effective approach to increasing the cycling performance. In particular, metal oxide-encapsulated carbon electrode materials have demonstrated superior cycling performances in LIBs[89]. Based on these concepts, the incorporation of metal fluoride into carbon materials, such as graphene, carbon fibers, CNTs, and mesoporous carbon materials, may lead to enhanced electrochemical properties. Therefore, Prakash et al. demonstrated ferrocene-based carbon-iron and LiF nanocomposite by pyrolysis of a mixture of LiF and ferrocene at 700 °C under an Ar atmosphere[90]. The composite was comprised of onion-type graphite structures and multi-walled CNTs, in which the LiF is dispersed within the carbon matrix and Fe3C and Fe nanoparticles are incorporated in the carbon matrix [Figure 5A and B]. The nanocomposite presents a specific surface area of 82 m2 g-1 and consists of both meso- (0.14 cm3 g-1) and micropores (0.025 cm3 g-1). The as-prepared cathode reached a reversible specific capacity of ~300 mAh g–1 at a current density of 20.83 mA g-1 with a potential range from 0.5 to 4.3 V. It showed good capacity retention (83.5% over 200 cycles) and excellent rate capability [Figure 5C and D]. Hence, due to its moderate capacity, more work is desired to optimize its reversible capacity, such as producing a uniform particle size/distribution, removing/reducing Fe3C, reducing the carbon content, obtaining more Fe-encapsulated CNTs, and so on. Similarly, another group fabricated FeF3 nanoflowers grown on CNT branch (FNCB)-based nanoarchitecture cathode materials by the functionalization of CNT surfaces[76]. The FNCBs exhibited improved electron transport and Li-ion storage when employed as cathode materials.

Figure 5. (A) TEM images of nanocomposite electrode after charging experiment. (B) Mossbauer spectrum of nanocomposite at 300 K. (C) Specific capacity and cycle performance of cathode. (D) Rate performance of as-prepared samples. Reproduced from Ref.[90] with permission. Copyright 2010 Royal Society of Chemistry.

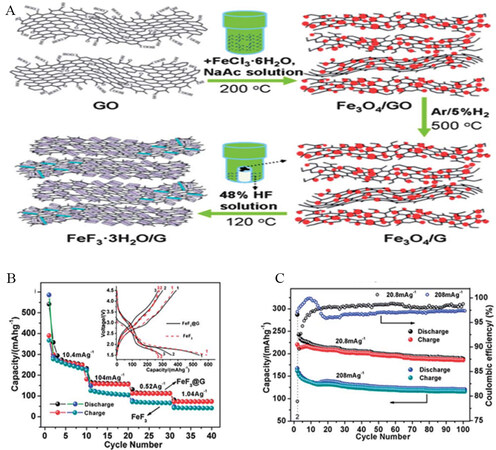

Graphene and reduced graphene oxide (RGO) stand out among carbon-based materials due to their outstanding mechanical properties and electrical conductivity[91-95]. Therefore, graphene sheets may be preferred conductive networks and building units to deliver facile electron pathways. A vapor-solid method was used for the first time to fabricate graphene-wrapped FeF3 nanocrystals (FeF3/G) as cathode materials

Figure 6. (A) Schematic illustration of fabrication procedure of FeF3/G nanocomposite. (B) Rate capability and (inset) voltage profiles of FeF3/G and bare FeF3. (C) Cycling performance and Coulombic efficiency of FeF3/G nanocomposite. Reproduced from Ref.[96] with permission. Copyright 2010 Royal Society of Chemistry.

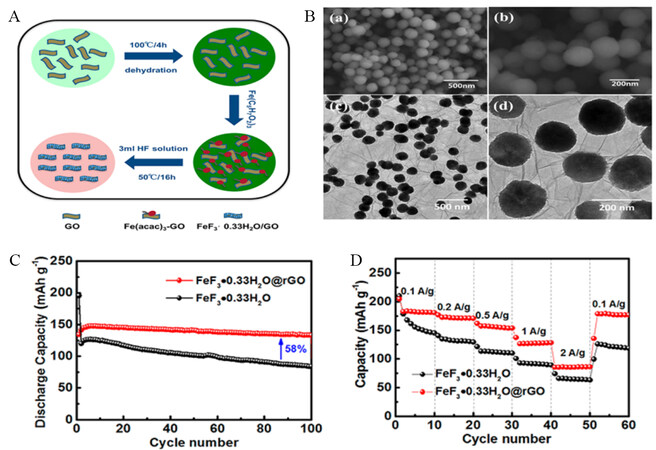

Similarly, Qiu et al. reported the seeding of FeF3·0.33H2O nanoparticles on RGO via an in situ approach and achieved enhanced cycling stability and high particle loading, attributed to the chemical tuning of the interfacial bonding between rGO and FeF3·0.33H2O [Figure 7A and B][98]. Specifically, the FeF3·0.33H2O/rGO nanocomposites exhibit a higher discharge capacity of ~208.3 mAh g-1 at a current density of 0.5C and excellent cycle stability (133.1 mAh g-1 after 100 cycles at 100 mA g-1) with 97% capacity retention

Figure 7. (A) Schematic illustration of preparation processes for FeF3·0.33H2O/rGO. (B) SEM and TEM images of FeF3·0.33H2O/rGO. (C) Cycling performance of FeF3·0.33H2O/rGO and FeF3·0.33H2O without rGO at a current density of 500 mA g-1. (D) Rate performance of FeF3·0.33H2O/rGO and FeF3·0.33H2O NPs. Reproduced from Ref.[98] with permission. Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

Previous research studies concentrated on introducing FeF3 particles to the surface of carbon matrices or infusing them inside the nanopores of RGO, CNTs, and mesoporous carbon[30,97,99]. However, the synthesis of carbon matrices requires complex synthetic methods and is costly. Moreover, successfully creating the intimate contact between carbon matrices and FeF3 nanoparticles is not easy, so avoiding the larger fraction of FeF3 outside the inner pores is very challenging[100]. Nevertheless, a FeF3-carbon composite with intimate contact between the conductive carbon matrices and FeF3 nanoparticles has been fabricated by modified carbonization and polymerization processes. This method can effectively enhance the intimate contact between carbon and FeF3 by the homogeneous mixing of FeCl3 (FeF3 precursors) with organic precursors (which can be converted into conductive carbon) at the molecular level. Thus, composites of FeF3 nanoparticles wrapped in graphitized carbon were prepared via a facile polymerization process using citric acid (C6H8O7), FeCl3, and ethylene glycol as a carbon source, iron precursor, and crosslinking agent, respectively[101]. The as-synthesized graphitic carbon-coated FeF3 composite displayed a capacity of

In comparison to inorganic materials, various organic compounds have also been considered electrode materials but have received less attention due to the development of conductive polymers (CPs) and the achievement of intercalation compounds (e.g., LiCoO2) in the 1980s as cathode materials for LIBs[102,103]. However, the intrinsic limits of intercalation compounds as cathodes for LIBs now desire innovation through the use of organic electrodes[104]. Therefore, carbonyl compounds are generally superior to CPs as electrode materials and are remarkable candidates for building low-cost, sustainable and functional energy storage systems[105]. For this reason, a hybrid FeF3@Li2C6O6/rGO nanocomposite was prepared by morphology control, intercalating RGO with spherical Li2C6O6, followed by modification with a FeF3 coating[106]. The as-prepared FeF3@Li2C6O6/rGO hybrid cathode displayed a superior cycling performance (320 mAh g-1 after 100 cycles), attributed to the coating of electrochemically active FeF3 on the surface of Li2C6O6, which successfully inhibited Li2C6O6 dissolution in the electrolyte. This interface engineering approach and morphology control represent a feasible and scalable technique to effectively increase the rate performance and cycling properties of organic-based cathode materials. Recently, Reddy et al. synthesized carbon-FeF2 nanocomposites by a facile one-step method at 250 °C, combining fluorinated carbon (CFx) with iron pentacarbonyl -[Fe(CO)5][107]. The resulting C-FeF2 nanocomposites act as the cathode and achieve improved electrochemical properties. By reacting Fe(CO)5 with four different CFx precursors, they synthesized four different C-FeF2 nanocomposites, which were made of carbon black, petcoke, carbon fibers, and graphite. The excellent electrochemical performance was also evaluated at 25 °C and 40 °C for high energy density LIBs.

Fu et al. reported an effective and versatile strategy for the development of metal fluoride-carbon nanofiber nanocomposites as flexible, free-standing cathodes[108]. The as-synthesized assembled FeF3-C/Li cells exhibit a higher discharge capacity of 550 mAh g-1 at 100 mA g-1 and demonstrated excellent stability (> 400 cycles with no structural degradation). These promising characteristics can be effectively attributed to the robustness of the electrically conductive carbon network, the nanoconfinement of FeF3 nanoparticles, reducing the irreversible separation and aggregation, the ultrafast pathways for electron transport and ion diffusion, and the inhibition of undesirable reactions between the liquid electrolyte and active materials.

Another effective and common method to enhance the electrochemical properties is the composite design of active materials. The first choice is always carbon-based metal fluoride composite electrodes. For instance, FeF2 nanoparticles confined into carbon nanofibers can suppress the side reactions between FeF2 and the electrolyte, thereby affording an enhanced electronic conductivity in the electrode and cycle stability over 400 cycles[108]. According to previously reported studies on battery electrode materials, the composite architecture design is a very capable approach to avoiding interactions between the active materials and electrolytes and accomplish fast transport in the electrode[109]. However, thus far, it is still a challenge to encapsulate nanosized FeF2, FeF3, CoF2, and CuF2 into a three-dimensional (3D) carbon matrix for the self-protection of electrodes and achieving fast electron and Li-ion transport. Simultaneously, the 3D architecture design can offer cathodes a high-active mass loading, high-rate performance, and good cycling stability. Therefore, Wu et al. prepared a FeF3@C composite with a 3D honeycomb architecture by a simple and facile method[110]. The isolated FeF3 particles with sizes of 10-50 nm were uniformly distributed in the 3D carbon honeycomb carbon framework, where the honeycomb carbon walls and hexagonal-like channels (cells) deliver sufficient conduction pathways for achieving fast ion diffusion and electron transport in FeF3 cathodes. According to the results of the report, the as-prepared 3D honeycomb architecture FeF3@C composite cathodes with high areal FeF3 loadings (2.2 to 5.3 mg cm-2) demonstrated an unprecedented rate capability of up to 100C and remarkable cycle stability within 1000 cycles, with high capacity retentions (95%-100%) within 200 cycles at 2C. As a result, it demonstrated that the 3D architecture with a honeycomb morphology represents a powerful strategy of composite design for metal fluorides in order to obtain exceptional electrochemical performance in metal fluoride Li batteries.

Overall, the results reported up to now display excellent potential for optimizing the architecture and composition of carbon-based metal fluoride cathodes to enhance their rate performance and cycling stability. Nevertheless, improving the electrochemical performance of carbon-based metal fluoride cathodes to the level of commercial applications still requires additional developments in novel fabrication techniques capable of precisely controlling the overall morphology and the nanoscale features of the carbon matrix and active materials. Therefore, more efforts are required to remove these issues for their commercialization.

Metal/metal oxide-based fluoride nanocomposites

Recently, the use of doping has been explored widely for intercalation-type electrode materials[111]. For conversion-type electrode materials, doping may also deliver obvious benefits to improve the ionic and electronic conductivities of electrode materials by enhancing the cathode performance through the intercalation of heterogeneous/homogenous metals, vacancies, or ions. Furthermore, many scientists have highlighted the possibility of decreasing the cluster size of creating ‘‘true’’ conversion electrode materials upon the lithiation process, attributed to the reduction in the interfacial energy and modification of the ion mobility of the clusters. As a result, this may improve the energy efficiency and cyclic stability of such electrodes because the affinity of the slow and steady separation of the cluster size could be diminished and the voltage hysteresis for the charge/discharge could be mitigated by reducing the paths for mass transport. In several recent reports, doping with Si has significantly enhanced the electronic conductivities of the electrode materials, with remarkable discharge capacity utilization obtained as a result[112].

Molybdenum bisulfide was ball milled with FeF3 to improve its electrochemical properties[113]. The orthorhombic structured FeF3/MoS2 with a uniform morphology showed excellent electrochemical performance as a cathode material in LIBs. The initial discharge capacity of the material was 170 mAh g-1 at a 0.1C rate with a voltage range from 2.0 to 4.5 V, and it maintained a specific capacity of 83.1% after 30 cycles. FeF3 with an orthorhombic structure was prepared by Wu et al.[87] via a liquid phase method using HF, FeCl3, and NaOH as precursors. The obtained product was further ball milled with conductive V2O5 powder to obtain a FeF3/V2O5 nanocomposite. The electrochemical properties of the prepared material showed a significant improvement after the addition of V2O5. The FeF3/V2O5 nanocomposite exhibited good rate and cycle performance. A discharge capacity of 209 mAh g-1 was obtained at a retention rate of 0.1C and a voltage range of 2.0-4.5 V and was maintained after 30 cycles.

A TiO2-coated FeF3·0.33H2O cathode material with a spherical morphology was prepared via a solvothermal method by Zhang et al.[114]. The nanosized FeF3·0.33H2O was coated with uniform TiO2 with an average particle size of ~1.0 μm and good dispersion ability. The initial reversible capacity at the retention rate of 0.1C was 654 (discharging) and 522 (charging) mAh g-1, respectively, with a voltage range of 1.5-4.5 V. After 200 cycles, a good stability of 264 mAh g-1 was maintained by the nanomaterial cathode, which demonstrated that the TiO2 layer on iron fluoride could be a promising cathode material for LIBs. A novel core-shell FeF3@Fe2O3 nanocomposite (100-150 nm) and tunable iron oxide (Fe2O3) were prepared via a simple heat treatment using fine structured FeF3 as a precursor[115]. The as-synthesized FeF3 and core-shell FeF3@Fe2O3 nanocomposites were characterized and their electrochemical performance was studied. A comparison between the pristine FeF3 and the FeF3@Fe2O3 nanocomposite revealed a significant improvement in the electrochemical performance upon the in situ coating of Fe2O3, even when the coating amount was 0.6-5.2 wt.%.

Metal doping has a positive effect on the charge/discharge capacity of metal fluoride cathode materials. The doped metal can increase the Li-ion diffusion coefficient and improve the electrochemical performance of the electrode materials. Recently, copper-doped FeF3 nanomaterials have been synthesized via a liquid-phase method[116]. The electrochemical reversibility of Fe1-xCoxF3 (x = 0, 0.03, 0.05 or 0.07) materials was further enhanced by the addition of acetylene black via mechanical a ball-milling process to obtain Fe1-xCoxF3/C nanocomposites. It showed a significant improvement in electrochemical performance with the introduction of cationic Co. The discharge capacities at retention rates of 1, 2, and 5C were 150, 140, and 125 mA h g-1 and maintained the capacity after 100 cycles as high as 92.0%, 92.2%, and 91.7%, respectively. Metal fluoride cathode materials can suffer from particle fracture during lithiation/delithiation in LIBs. To improve the cathode nanoparticle stability and overcome this phenomenon, Co doping has been carried out for FeF3 in LIBs by Zhang et al.[117]. In this study, calculations for Co doping onto the hexagonal tungsten bronze structure were carried out successfully to form CoxFe1-xF3 systems (x = 0.08, 0.17 or 0.25). The study showed a sharp decrease in the band after Co doping, which may be attributed to the presence of Co 3d impurity energy levels between the conduction and valence bands. A thermally stable Co-doped iron fluoride (Fe0.9Co0.1F3·0.5H2O) was synthesized by a non-aqueous precipitation method as a cathode material for LIBs[118]. The thermogravimetric analysis shows that the cathode nanomaterial was stable until 243 °C, with the crystal structure collapsing beyond this temperature due to water content elimination. The Co-doped cathode material showed a high discharge capacity (227 mAh g-1) during cell cycling and retained a reversible capacity of 150 mAh g-1 after 200 cycles.

A significant boost in the electrochemical performance of FeF2 cathode materials was found after the addition of NiF2 nanomaterials for LIBs by Huang et al.[119]. The data obtained revealed the precise control of morphology and composition of the desired FeF2-NiF2 nanoparticles and undesirably enhanced capacity fading of the electrochemical cell. In another study, the substitution of Ni with Cu was carried out for binary NiF2 nanomaterials and their electrochemical performance was studied for LIBs[120]. From in situ TEM, the structure of different ternary metal fluorides with Cu substitution was observed and the results revealed that when the Cu substitution was from 1-25 wt.%, the areal expansion reduced during the first lithiation. Furthermore, due to the reversible reaction, the fluorine loss during the delithiation was also reduced, which proved Cu to be a better choice for substitution to improve the electrochemical performance. Recently, ternary metal fluorides, like AgCuF3 and CuxFe1-xF2, have been used as cathode materials in LIBs by

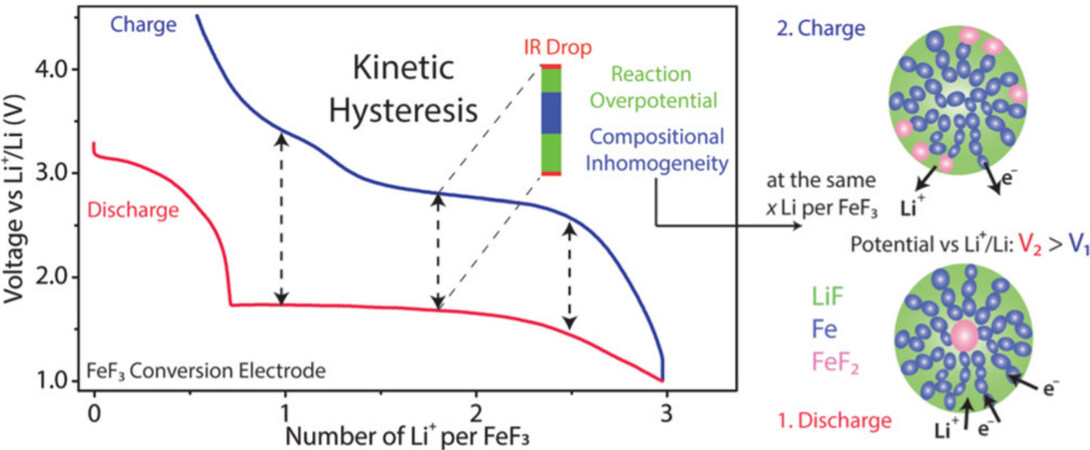

Voltage hysteresis

Hysteresis is a common problem between the charge and discharge potentials in rechargeable batteries, which is related to thermodynamic and kinetic factors[9,10,18]. It may reduce capacity utilization and leads to low energy efficiency. In addition, the charge and discharge window with a larger voltage hysteresis may introduce more side reactions between the active substance and electrolyte and possibly unstable SEI. Unfortunately, MF cathodes show undesirably large voltage hysteresis, which is typically related to the poor electronic conductivity of the materials, rapid degradation of the battery, and changes in surface/interfacial energies during the conversion reactions. Energy losses for compensating the activation energies of breaking chemical bonds are also another key reason for voltage hysteresis. The discharge process (lithiation) of MF cathodes involves breaking Fe-F bonds and forming lower free-energy compounds containing lithium. The products from discharge process, such as LiF (bonding energy of Li-F is 577 kJ mol-1), are thermodynamically stable due to the large electronegativity difference between Li and F. The charge process (reverse reaction) is required to decompose LiF by breaking the stronger corresponding chemical bonds. This introduces a large activation energy barrier, which contributes to a large voltage hysteresis (overpotential). This large voltage hysteresis even leads to the misapprehension that cells based on conversion MF cathodes are only primary batteries, such as Li-CuF2 battery systems[50,55,60].

Recently, Li et al.[48] employed in situ analytical techniques to correlate the voltage profile with intermediate phases of FeF3, which involved the evolution and spatial distribution of intermediate phases during the discharge-charge process. The results show that the phase evolution in the electrode is symmetric during cycling. However, the spatial evolution of the electrochemically active phase controlled by the reaction kinetics is different. They found that the kinetics of the FeF3 electrode in nature is the reason for the voltage hysteresis. It originates from the Ohmic voltage drop, overpotential, and different spatial distributions of active phases, as shown in Figure 8. Therefore, the large hysteresis can be alleviated through the reasonable optimization of the material and electrode microstructure.

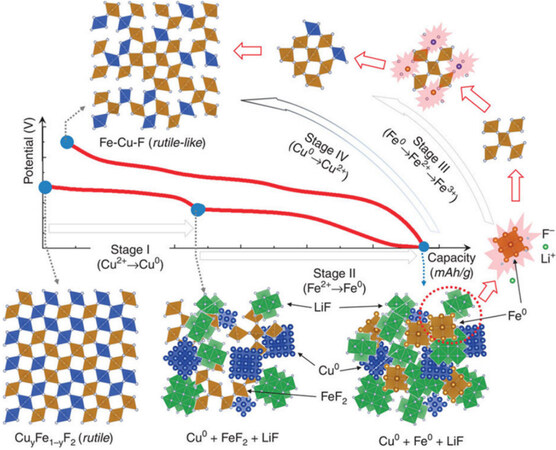

Figure 8. Schematic illustration of phase evolution in the electrode during discharge and charge. Reproduced from Ref.[48] with permission. Copyright 2016 American Chemical Society.

Elemental doping is a promising approach for conversion-type materials to overcome the problem of voltage hysteresis. The ionic and electronic conductivities of the electrode material are enhanced by the introduction of homogeneous/heterogeneous metallic (non-metallic) ions or vacancies. For example, FeF2 doped with Cu and FeF3 doped with Co showed lower voltage hysteresis. The partial substitution of F with O in FeF3 greatly improves the reaction kinetics, reduces voltage hysteresis, and exhibits excellent cycle performance over 100 cycles (for this chemistry). Recently, Wang et al. proposed a novel strategy to make full use of the Cu2+/Cu0 redox range for the first time in the application of copper-based fluorine rechargeable Li batteries[122]. The prepared FeF2 (tetragonal rutile) and CuF2 (monoclinal distorted rutile) solid solutions gave Cu1-xFexF2 a tetragonal rutile structure with high symmetry. It involves a two-stage lithiation process during the discharge process of the Cu1-xFexF2 cathode. The first stage is at an upper plateau of ~2.9 V, which is related with a Cu-based conversion reaction, in a similar potential range as CuF2. The second stage is at a higher potential of ~2.2 V, which is related with a Fe-based conversion reaction, as shown in Figure 9. Cu0.5Fe0.5F2 displays a reversible capacity of 543 mAh g-1 at the first discharge-charge process. As-prepared cathode materials show enhanced dynamic performance, which lies in a reduction of the voltage hysteresis and the elimination of the voltage drop observed in FeF2. After first-half conversion, the lattice disorder in FeF2 increases due to the down-sizing of FeF2, which is responsible for the disappearance of voltage drop and higher discharge voltage during the initial second-half conversion. There is a small voltage hysteresis of Cu2+/Cu0 due to the low nucleation barrier for the formation/decomposition of the Cu-F bond.

Figure 9. Illustration of potential reaction pathway of Cu1-xFexF2 during discharge-charge. During discharge (stages I and II), Cu and Fe occur sequentially by the conversion reduction. During charge, the oxidation processes of Fe and Cu (stages III and IV) overlap to reform the disordered rutile-like Cu-Fe-F phase. Reproduced from Ref.[122] with permission. Copyright 2015 The Author(s).

Side reactions with electrolytes

The unfavorable side reactions between electrodes and electrolytes increase voltage hysteresis, reduce the Coulombic efficiency and stability of the cathode SEI and induce a safety hazard. There are multiple roles for the SEI, including limiting side reactions between the cathode (or anode) and the electrolyte. An ideal SEI layer has properties that include high cation conductance and electrical resistance, a thickness of a few nanometers, high mechanical toughness, and stability over a wide range of voltages. A stable SEI is an accepted prerequisite for safe battery performance, be it with a metal or an ion insertion anode. In theory, conversion-type cathodes should be advantageous in the thermodynamic stability of electrolytes because of their low electrochemical potentials (1.5-4.0 V vs. Li/Li+). However, the oxidation stability of electrolytes can be changed by various salt anions, especially in concentrated electrolytes, and certain cathode chemicals. In addition, since the conversion cathode is usually discharged to a relatively low potential vs. Li/Li+ (sometimes down to 1.2 V), the electrolyte may be reduced at the cathode surface. At moderate cathode potentials, the various substances formed by electrolyte reduction are more easily oxidized than the original electrolyte. Furthermore, some conversion cathode species may also catalyze the reduction reaction. For example, it has been found that the cyclic stability of MFs is worsened by the formation of a lithium carbonate species, which is susceptible to nanometal catalyzed reduction during the battery discharge to 1.2-2.0 V. The continuous large volume changes during cycling may prevent stabilization of the cathode SEI with poor elasticity in conversion-type cathodes. However, in contrast, the formation of a stable cathode SEI may also contribute to the stabilization of the conversion cathode, preventing adverse reactions between the cathode and electrolyte.

In the case of liquid electrolytes, modifications have been made to the composition of lithium salts, organic solvents, salt concentrations, and organic and inorganic electrolyte additives in an attempt to alleviate the limitations of cathodes based on the conversion reaction. For intercalated cathodes and graphite anodes, classic organic carbonate esters are commonly used solvents, such as ethyl carbonate, propylene carbonate, ethyl carbonate, and ethyl carbonate. However, for the partial conversion of the cathode, the carbonate solvents may cause some adverse reactions. To address this problem, an electrolyte with a high concentration of LiTFSI salt has recently been developed to inhibit the dissolution of cathode materials by in situ forming a protective layer penetration on the surface of the electrode. In contrast, an ultrathin artificial SEI layer was prepared by atomic layer deposition, and it was reported that the conformation of the layer covered with fluorine particles reduced the side reaction between fluorine and the electrolyte. For example, 3D Al2O3-coated FeF2 nanoparticles were prepared on Ni support by Kim et al.[83]. The results revealed that the electrochemical applications of the as-prepared electrode were significantly improved due to the ion transport pathway. The initial discharge capacity of the 3D FeF2 electrode was 380 mAh g-1 at

SYNTHESIS OF METAL FLUORIDES

The reported results show excellent potential for improving the battery performance of metal fluoride cathodes by optimizing the composition and architecture of the cathode. However, in order to control the size features and morphology of the conversion-type cathode materials, novel synthesis technologies should be further developed to optimize the performance of cathode chemistries to the level of commercial applications. Metal fluoride electrodes have been prepared via different chemical and physical methods. The electrochemical performance of the metal fluoride cathode materials has shown significant improvements based on the specific synthesis method involved in forming nanoscale architectures. The low ionic and electronic conductivities of the metal fluorides can be improved either with homogenous mixing with a highly conductive material or by reducing the particle size. Because nanoparticles can shorten the Li-ion diffusion time and provide a high surface area for contact with the electrolytes. Furthermore, nanostructured electrode materials have the ability to resist/hinder stress and strain from volume changes. The specific nanoscale morphology has proven to have an enormous impact on the specific capacity and cyclic stability of the electrode materials. In this section, the strategies employed to synthesize electrode materials are introduced, including hydrothermal, solvothermal, microwave synthesis, vapor-solid, ion synthesis and sol-gel methods.

Hydrothermal methods

Hydrothermal methods have often been used in synthetic chemistry due to the advantages of the crystalline powder at high temperatures. The controlled reaction conditions of the hydrothermal process result in the desired morphology[123-125]. In this process, the product prepared has good dispersion, high purity, uniform morphology and controlled particle size. It can be used to synthesize monocrystalline materials, as well as 2D and 3D materials, with particle sizes ranging from microns to nanometers.

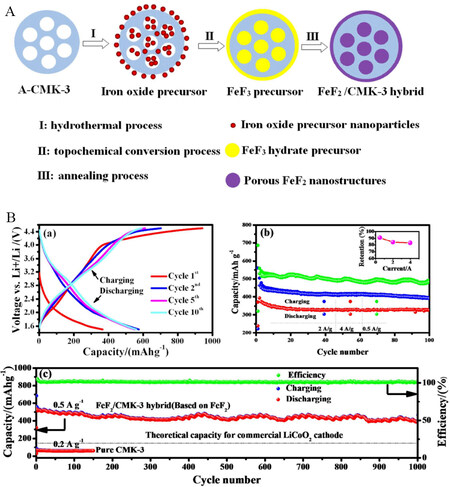

The low electronic conductivity of FeF2 cathode nanomaterials for LIBs was enhanced via the incorporation of ordered mesoporous carbon (CMK-3)[126]. The FeF3 precursor was synthesized with the hydrothermal treatment of CMK-3 and iron oxide, followed by a topochemical process. The FeF3 precursor was further annealed to obtain a hierarchical conductive FeF2/CMK-3 nanoparticle network, as shown in Figure 10A. This type of hierarchical structure offers continuous electronic conduction within the network and porosity for the volume expansion of the prepared material. The prepared cathode material showed a stable cycle life of 1000 cycles with 0.3% capacity loss per cycle. After 100 cycles, high discharge capacities at current densities of 500, 2000, and 4000 mA g-1 were 500, 400, and 320 mAhg-1, respectively, as shown in Figure 10B.

Figure 10. (A) Schematic illustration of the synthesis of porous FeF2-CMK-3 composite. (B) Electrochemical performance of FeF2/CMK-3 cathodes: (a) charge-discharge profiles at 200 mAg-1; (b) and (c) cycling performance. Reproduced from Ref.[126] with permission. Copyright 2015 Royal Society of Chemistry.

Solvothermal methods

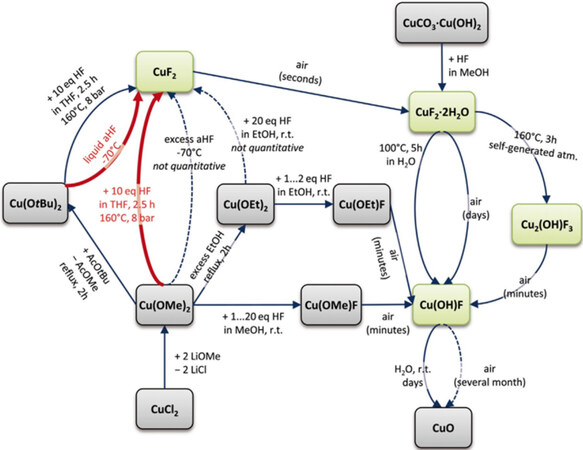

Solvothermal methods are actually developed based on hydrothermal methods, except that the reaction medium is organic solvent rather than water. In a solvothermal process, one or more precursors in the reaction are dissolved under critical circumstances. This process has numerous advantages, including short reaction times, fast reaction kinetics, uniform particle distribution and high crystallinity. The electrode materials obtained by solvothermal methods have shown enhanced electrochemical performance, including good rate performance and long cycle life[127-129]. Recently, anhydrous CuF2 nanomaterials from alkoxides Cu(OR)2 (R = Me or tBu) were synthesized in hydrofluoric acid and tetrahydrofuran as reaction media[130]. A schematic diagram of the process is shown in Figure 11. Depending on the reaction conditions, different sizes of 10 and 100 nm nanoparticles were obtained. The product was found to be very hygroscopic and formed various hydrated products, including Cu(OH)F, CuF2·2H2O, and Cu2(OH)F3. The as-prepared nanomaterials showed high electrochemical performance at a potential ~2.7 V for Li-ion charge/discharge. Different specific capacities were obtained with different particle sizes, e.g., 468 and 353 mAh g-1 for ~8 and ~12 nm crystalline diameters, respectively, for CuF2. The high specific capacity of the nanomaterials faded after several cycles and the cell voltage decreased to 2.0 V, which was attributed to the irreversible nature of the reacting material involved in the electrochemical cell reaction.

Figure 11. Overview of synthesis reactions. Thick red arrows represent most suitable reactions toward CuF2. Dashed arrows represent product mixtures. Green boxes represent compounds used for electrochemical investigations. Reproduced from Ref.[130] with permission. Copyright 2018 Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim.

In another study, Fe(1-x)CoxF3/multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) nanocomposites were synthesized by a solvothermal method[131]. The iron fluoride nanomaterials doped with Co were wrapped with MWCNTs. The results of the prepared materials revealed the crystal structure adjustment, decreased the band gap, and enhanced the Li-ion diffusion capacity after Co doping. Moreover, the MWCNT wrapping increased the conductivity, which in turn enhanced the electrochemical performance of the Fe0.96Co0.04F3/MWCNT nanocomposites. The high specific capacity of the nanocomposites at 2.0-4.5 V recorded was 217.0 mAh g-1 at a rate of 0.2 C. The electrochemical performance was higher compared to the FeF3/MWCNT nanocomposite counterparts. After 50 cycles, the specific capacity of the two nanocomposites decreased to 187.9 and 160.7 mAh g-1, respectively, which showed the cyclic stability of the prepared nanocomposites for Li storage in Li batteries.

Microwave-assisted methods

For the synthesis of metal fluoride nanomaterials, microwave-assisted approaches are promising routes compared to other synthetic methods. Since its first report in the field of synthetic chemistry and materials synthesis, this method has grown rapidly in this area of research[132]. By this method, the reaction entirely depends on the rapid heating, which produces reagents and solvents and makes this different from other methods, e.g., hydrothermal and solvothermal methods. Furthermore, the fast heated reaction results in a high reaction rate and efficiency and lower energy consumption[133]. In recent years, to obtain the tailorable morphologies, a combination of room-temperature ILs and a microwave heating process have been used[134]. A microwave-assisted approach was followed for the successful synthesis of self-assembled iron fluorides (HMIFs) with a hierarchical mesoporous structure[39]. The detailed possible steps and mechanism are shown in Figure 12. The dual nature fluorides, consisting of FeF3·H2O and Fe1.9F4.75·0.95H2O, were built from a large number of nanorods with more than a dozen nanometer size and their electrochemical performance in LIBs investigated. The as-prepared HMIFs exhibited a homogeneous morphology with a hierarchical mesoporous structure and partial internal hollow core and possessed a specific area of

Figure 12. Schematic diagram of formation mechanism of partially hollow HMIFs. From steps 1 to 5: mixing the reactants; combining the solvated ions; initial stage emerging of nanoparticles; Ostwald ripening process; final state of the products. Reproduced from Ref.[39] with permission. Copyright 2014 Royal Society of Chemistry.

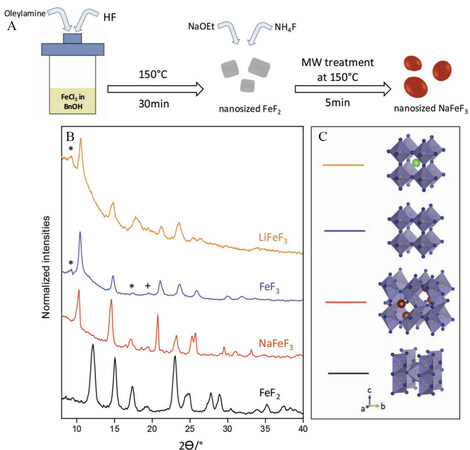

Nanosized NaFeF3 perovskite particles were synthesized from sodium ethoxide, ammonium fluoride and pre-synthesized FeF2 rutile colloidal particles via a microwave-assisted method[135]. A schematic diagram, powder X-ray diffraction phases, which confirmed the expected crystal structure of rutile and orthorhombic-type crystal, and the 3D structure models are shown in Figure 13. The as-prepared perovskite NaFeF3 nanomaterials showed excellent electrochemical performance with low polarization for Na and Li storage in energy storage devices. This enhanced performance of excellent capacity retention is attributed to the stable corner-sharing cubic Li and Na perovskite with stable cycle and low volume change and thermodynamic cost, as supported by a polymorphism theoretical study.

Figure 13. (A) Synthetic process of NaFeF3 electrode material. (B) XRD patterns of as-prepared FeF2 and NaFeF3. (C) 3D structural models from XRD experiments. Reproduced from Ref.[135] with permission. Copyright 2019 Wiley‐VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim

Sol-gel methods

Sol-gel methods are versatile routes in synthetic chemistry for designing complex nanostructures with controlled particle size, the arrangement of nanopores, and uniform particle distributions. The nanoporous behavior of the particle has the property of being functionalized during the gel formation even in a dry state by polymers or other active organic molecules. Upon careful heat treatment and utilization of the reaction precursor solution with temperature control, nanoparticles can be grown within the nanopores, which can be used in different applications with excellent performance[136]. There are some unique advantages of the sol-gel method, which make this process special compared to other conventional methods used for nanomaterial preparation. The first is the formation of a viscous solution from the dispersion of the raw materials during the process. A homogeneous mixture is achieved in a short period and even after the gel is formed, a molecular level homogeneous solution of the reactants is obtained. The second is that during the reaction, it is easy to add other materials, so molecular-level homogeneous doping is possible. The third is that the reaction can be carried out even at low temperatures and easily compared to the reaction involving solid components. This is because, in the sol-gel method, the reactants diffuse in the nanometer range, while for solid particles, the diffusion is at the micro level, and as a result, low temperature is required for the nanoscale formation.

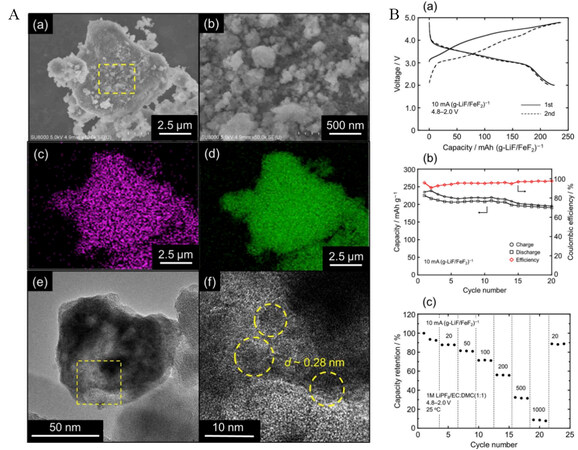

FeF3 nanocrystals as electrodes for LIBs with a particle size of 30 nm were prepared by a sol-gel method[137]. To enhance the electrochemical performance, the as-synthesized particles were fabricated with RGO, which shows a high specific retention of 150 mA h g-1 and stable cycle life for Li ions, even after 50 cycles. In another study, LiF- and FeF2-based nanocomposites were prepared via a sol-gel method in ethanol for LIBs[138]. The SEM and TEM characterization of the LiF/FeF2 composite proved that ~10 nm nanosized LiF and FeF2 crystals were obtained, as shown in Figure 14A, with EDX and XRD analysis and a large surface area of 119 m2 g-1. The large surface and adsorption-desorption hysteresis revealed the presence of mesopores, which might have a positive impact on the electrochemical performance. The initial discharge specific capacity of the reversible conversion reaction for the nanocomposites recorded was 225 mAh g-1 at a current rate of 10 mA g-1 with a stable life cycle, as shown in Figure 14B.

Figure 14. (A) (a) and (b) SEM images of LiF-FeF2 composite. EDX mappings of (c) Fe and (d) F. (e) and (f) TEM images of LiF-FeF2 electrode. (B) Charge-discharge performance: (a) charge-discharge profiles at current density of 10 mA g-1; (b) cycling performance for first 20 cycles at 10 mA g-1; (c) rate capability (from 10 to 1000 mA g-1). Reproduced from Ref.[138] with permission. Copyright 2019 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Ionothermal methods

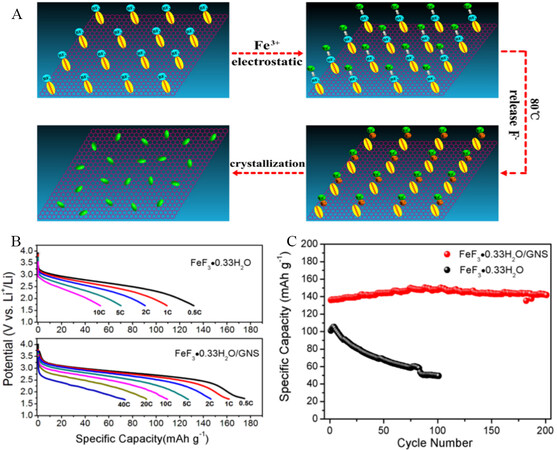

Ionic liquids (ILs) have been discovered as alternatives to conventional solvents[139]. ILs are composed of cations and anions, in which one of them should be naturally organic and have a melting point below some arbitrary temperature[140]. This class of solvent is divided into two major groups based on their melting points, namely, room-temperature ILs, which melt at room temperature, and near room-temperature ILs, which have a melting point below 100 °C. Low vapor pressure is the distinguishing feature that makes them different from other solvents[141]. ILs were categorized as convenient alternatives to organic solvents much later, although they were recognized as solvents at the beginning of the 20th century. The main characteristics of ILs include good electric conductivity, fire resistance, high thermal stability, ability to dissolve many inorganic and organic compounds, nonvolatile, a wide range of temperatures, and recyclability[142,143]. These characteristics made ILs a good choice for energy storage devices. The in situ synthesis of FeF3/GNS nanosheet hybrid nanomaterials was developed via an IL-assisted method[144]. The role of ILs was not only as green fluoride sources but also to provide uniform dispersion and tight surface modification of FeF3·0.33H2O on graphene nanosheets. The synthesis procedure of FeF3·0.33H2O/GNS and the discharge profile at different currents are shown in Figure 15, where it can be seen that the as-synthesized FeF3·0.33H2O/GNS cathode nanomaterials showed an extensive enhancement in both specific capacity and rate performance due to the electron transfer path of the iron nanoparticles and GNS in LIBs. The cyclic stability proves the strong adhesion of iron fluoride nanoparticles, which have a significant electrochemical performance of 115 mAh g-1 after 250 cycles, even at 10C, which is attributed to the strong structure of the hybrid and robust interaction between graphene and iron fluoride nanoparticles. In another study, mesoporous FeF3·0.33H2O cathode materials for LIBs were prepared at low temperatures via ILs as reaction media[23]. The enhanced electrochemical performance in terms of high reversible capacity and reactive voltage of the carbon free FeF3·0.33H2O cathode materials in LIBs was expected due to the morphology and optimization of hydration of the water-induced microstructure at room temperature.

Figure 15. (A) Synthetic process of FeF3·0.33H2O/GNS composite. (B) Discharge profiles and (C) cycling performance of FeF3·0.33H2O/GNS composite and FeF3·0.33H2O without GNS. Reproduced from Ref.[144] with permission. Copyright 2013 American Chemical Society.

Vapor-solid methods

A vapor-solid method was used to thermally convert Fe3O4/graphene into FeF3/G cathode materials for LIBs[145]. This method has several advantages and has been used to prepare MF electrode materials for energy storage devices. This versatile method can be applied to prepare FeF3 and metal oxide cathodes from Fe oxides/hydroxides and can be used to fabricate MxFy or MxFy/G composites for LIBs. Furthermore, this process can resist the increase in particle size due to the electronegativity of Fe, whose particles grow rapidly after nucleation compared to other solution-based processes. The conversion rate of FeF3 from Fe3O4/G is also high and the product yield is good. The fabrication of porous carbon materials was successfully achieved on FeF3 to prepare FeF3/C nanocomposites in a tailored autoclave via a vapor-solid method[99]. The phase changes during the reaction between the HF solution and precursors in an Ar atmosphere were examined, and the results revealed that the autoclave had a vital role in driving the reaction to form FeF3 nanomaterials. The charge capacity of the as-prepared FeF3/C nanocomposites was 134.3, 103.2, and 71.0 mAh g-1 at different current densities of 100, 500, and 1000 mA g-1, which are superior compared to the bare FeF3 materials and displayed stable cyclic performance with a charge capacity of 200 mAh g-1.

CURRENT CHALLENGES AND FUTURE OPPORTUNITIES

Metal fluorides have been used as electrode materials and offer significant advantages to rechargeable Li batteries with improved safety and low costs. Metal fluoride cathode materials give up to a 50% higher volumetric energy density and double the cell-level specific energy compared to other intercalation cathodes. However, the industrial application of metal fluoride conversion cathode materials is still limited due to several scientific challenges. These limitations include irreversible structural changes, volume change during cycling, active material dissolution, unfavorable interactions with electrolytes, large voltage hysteresis, and low electronic conductivity.

Some disadvantages of metal fluoride electrodes make them incongruous for practical energy storage devices. Firstly, in LIBs, the LiF produced during conversion reactions is highly insulated, which causes many problems during cycling, such as large voltage hysteresis and low electronic conductivity. Secondly, the volume changes during lithiation/delithiation can induce obvious decomposition of the SEI film. There have been several approaches to mitigate the challenges of metal fluoride electrode materials and make them promising choices for energy storage devices.

The conversion reactions of metal fluorides typically involve the breaking of bonds with transition metals, highly insulated products (e.g., LiF), and complicated reaction pathways. These features are responsible for cycling problems and voltage hysteresis. Although some reports have provided insight into such problems, more detailed insights are expected from advanced characterization and simulation tools. It is difficult to obtain deeper information from routine tools (such as TEM, SEM and XRD) due to the poorly crystallized conversion products. Therefore, advanced tools, such as PDF, NMR, EELS, TXM, and XAS, should be explored for studying conversion processes, which are sensitive to light elements and the finer microstructural details of the local structure.

The SEI is always an important but often neglected factor for the battery performance with metal fluoride cathodes. The SEI layer can become thicker during cycling, which causes the loss of active species and larger Fe interparticle distances, resulting in the capacity fade of the electrode. The growth of SEI layers is not desired for batteries as it can retard ionic and electronic transport. Artificial SEI layers (e.g., surface coatings) and optimizing the composition of the electrolyte, such as using a high concentration LiTFSI salt, may be efficient methods to solve these problems faced by the in situ formation of a protection layer at the electrode surface. In any case, SEI issues should be given more attention to obtaining good cycling stability.

One of the greatest challenges for metal fluorides is to improve their conversion energy efficiency by reducing the reaction overpotential. The energy density of FeF3 is up to 1341.7 and 1899.13 Wh kg-1 during discharge and charge at 100 mA g-1, respectively[146]. The conversion energy efficiency is only 70.7%, which is lower than the values for transition metal oxides (95.8% for NMC and 93.9% for LiFePO4), as shown in Figure 16. To solve this problem, more focus should be devoted to the design of external wiring networks and the topological structure in future research. The surface defect chemistry (metastable or framework phases) of metal fluorides should also be considered to further optimize the spatial distribution of pristine phases, conversion products, and conductive network components in electrodes. One of the key tools is the defect chemistry of the involved phases including stoichiometric variations and doping. A promising method of improving the kinetics would use liquid-solid conversion mechanisms instead of the solid-solid conversion path. Therefore, it is worth studying conversion reactions involving Fe and LiBF4 rather than LiF or considering boron-based additives as F- receptors to dissociate LiF. Exploring electrolytes additives, separators and binders are also necessary for metal fluoride materials to suppress cathode dissolution effects and anode dendrite growth in the future.

Figure 16. Energy efficiency and density of (A) FeF3, (B) LiFePO4 and (C) transition metal oxide (NMC) based on their discharge-charge curves. Reproduced from Ref.[146] with permission. Copyright 2018 The Author(s).

In summary, the strategies for enhancing fluoride cathodes include: (1) the optimization of nanostructures for the formation of new desirable material, which will minimize the paths for Li ion diffusion and result in high electrochemical performance. An appropriate synthesis method could have a vital role in synthesizing desired nanoscale structures to obtain an advanced architecture of active metal fluoride materials; (2) achieving faster mass charge transport by building block and defect chemical variation in structures and (3) development or optimization of the electrolytes involved and the formation of advanced cell component solutions. It is obvious that to advance these electrode materials and make them ideal, numerous approaches have been employed to enhance the electrochemical performance, but significant improvements are still required for the practical applications of metal fluoride electrode materials.

DECLARATIONS

Authors’ contributionsPreparing the manuscript draft, writing-review, editing, funding acquisition: Ma D

Writing-review: Zhang R, Chen Y

Collecting literature: Xiao C, He F, Zhang S, Chen J

Funding acquisition, supervision: Hu X, Hu G

Availability of data and materialsNot applicable.

Financial support and sponsorshipThis work was supported by the projects from National Natural Science Foundation of China (51802114, 21503008 and U2002213), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China (ZR2019BF027). the Double Tops Joint Fund of the Yunnan Science and Technology Bureau and Yunnan University (2019FY003025), and Double First-Class University Plan (C176220100042). Key Discipline of Materials Science and Engineering, Chizhou University (czxyylxk03). Anhui Province materials and chemical industry first-class undergraduate talents demonstration leading base (2020rcsfjd28).

Conflicts of interestAll authors declared that there are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participateNot applicable.

Consent for publicationNot applicable.

Copyright© The Author(s) 2022.

REFERENCES

1. Watanabe N. Two types of graphite fluorides, CF.n and C2F.n, and discharge characteristics and mechanisms of electrodes of CF.n and C2F.n in lithium batteries. Solid State Ionics 1980;1:87-110.

2. Feuillade G, Perche P. Ion-conductive macromolecular gels and membranes for solid lithium cells. J Appl Electrochem 1975;5:63-9.

3. Wang L, Wu Z, Zou J, et al. Li-free cathode materials for high energy density lithium batteries. Joule 2019;3:2086-102.

4. Dey AN. Experimental optimization of Li/SOCl2 primary cells with respect to the electrolyte and the cathode compositions. J Electrochem Soc 1976;123:1262-1264. Available from: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1149/1.2133057/meta [Last accessed on 26 Jul 2022.

5. Whittingham MS. Chemistry of intercalation compounds: metal guests in chalcogenide hosts. Prog Solid State Chem 1978;12:41-99.

6. Xiao Q, Yang J, Wang X, et al. Carbon-based flexible self-supporting cathode for lithium-sulfur batteries: progress and perspective. Carbon Energy 2021;3:271-302.

7. Hua X, Eggeman AS, Castillo-Martínez E, et al. Revisiting metal fluorides as lithium-ion battery cathodes. Nat Mater 2021;20:841-50.

8. Xiao AW, Lee HJ, Capone I, et al. Understanding the conversion mechanism and performance of monodisperse FeF2 nanocrystal cathodes. Nat Mater 2020;19:644-54.

9. Karki K, Wu L, Ma Y, et al. Revisiting conversion reaction mechanisms in lithium batteries: lithiation-driven topotactic transformation in FeF2. J Am Chem Soc 2018;140:17915-22.

10. Wu F, Yushin G. Conversion cathodes for rechargeable lithium and lithium-ion batteries. Energy Environ Sci 2017;10:435-59.

11. Castillo J, Qiao L, Santiago A, et al. Perspective of polymer-based solid-state Li-S batteries. Energy Mater 2022;2:200003.

12. Tao J, Yan Z, Yang J, Li J, Lin Y, Huang Z. Boosting the cell performance of the SiO x @C anode material via rational design of a Si-valence gradient. Carbon Energy 2022;4:129-41.

13. Yamakawa N, Jiang M, Key B, Grey CP. Identifying the local structures formed during lithiation of the conversion material, iron fluoride, in a Li ion battery: a solid-state NMR, X-ray diffraction, and pair distribution function analysis study. J Am Chem Soc 2009;131:10525-36.

14. Li C, Mu X, van Aken PA, Maier J. A high-capacity cathode for lithium batteries consisting of porous microspheres of highly amorphized iron fluoride densified from its open parent phase. Adv Energy Mater 2013;3:113-9.

15. Gu W, Magasinski A, Zdyrko B, Yushin G. Metal fluorides nanoconfined in carbon nanopores as reversible high capacity cathodes for Li and Li-ion rechargeable batteries: FeF2 as an example. Adv Energy Mater 2015;5:n/a-n/a.

16. Li L, Meng F, Jin S. High-capacity lithium-ion battery conversion cathodes based on iron fluoride nanowires and insights into the conversion mechanism. Nano Lett 2012;12:6030-7.

17. Wang X, Gu W, Lee JT, et al. Carbon nanotube-CoF2 multifunctional cathode for lithium ion batteries: effect of electrolyte on cycle stability. Small 2015;11:5164-73.

18. Wang Y, Xu H, Zhong J, et al. Hierarchical Ni/Co-based oxynitride nanoarrays with superior lithiophilicity for high-performance lithium metal anode. Energy Mater 2021;1:100012.

19. Li H, Richter G, Maier J. Reversible formation and decomposition of LiF clusters using transition metal fluorides as precursors and their application in rechargeable Li batteries. Adv Mater 2003;15:736-9.

20. Ma D, Cao Z, Wang H, Huang X, Wang L, Zhang X. Three-dimensionally ordered macroporous FeF3 and its in situ homogenous polymerization coating for high energy and power density lithium ion batteries. Energy Environ Sci 2012;5:8538.

21. Makimura Y, Rougier A, Tarascon J. Pulsed laser deposited iron fluoride thin films for lithium-ion batteries. Appl Surf Sci 2006;252:4587-92.

22. Zhang H, Zhou Y, Sun Q, Fu Z. Nanostructured nickel fluoride thin film as a new Li storage material. Solid State Sci 2008;10:1166-72.

23. Li C, Gu L, Tsukimoto S, van Aken PA, Maier J. Low-temperature ionic-liquid-based synthesis of nanostructured iron-based fluoride cathodes for lithium batteries. Adv Mater 2010;22:3650-4.

24. Gonzalo E, Kuhn A, García-alvarado F. On the room temperature synthesis of monoclinic Li3FeF6: a new cathode material for rechargeable lithium batteries. J Power Sources 2010;195:4990-6.

25. Li C, Gu L, Tong J, Tsukimoto S, Maier J. A mesoporous iron-based fluoride cathode of tunnel structure for rechargeable lithium batteries. Adv Funct Mater 2011;21:1391-7.

26. Cui Y, Xue M, Zhou Y, Peng S, Wang X, Fu Z. The investigation on electrochemical reaction mechanism of CuF2 thin film with lithium. Electrochim Acta 2011;56:2328-35.

27. Wang F, Robert R, Chernova NA, et al. Conversion reaction mechanisms in lithium ion batteries: study of the binary metal fluoride electrodes. J Am Chem Soc 2011;133:18828-36.

28. Rangan S, Thorpe R, Bartynski RA, et al. Conversion reaction of FeF2 thin films upon exposure to atomic lithium. J Phys Chem C 2012;116:10498-503.

29. Liu P, Vajo JJ, Wang JS, Li W, Liu J. Thermodynamics and Kinetics of the Li/FeF3 reaction by electrochemical analysis. J Phys Chem C 2012;116:6467-73.

30. Zhao X, Hayner CM, Kung MC, Kung HH. Photothermal-assisted fabrication of iron fluoride-graphene composite paper cathodes for high-energy lithium-ion batteries. Chem Commun 2012;48:9909-11.

31. Li C, Yin C, Gu L, et al. An FeF(3)·0.5H2O polytype: a microporous framework compound with intersecting tunnels for Li and Na batteries. J Am Chem Soc 2013;135:11425-8.

32. Chu Q, Xing Z, Tian J, et al. Facile preparation of porous FeF3 nanospheres as cathode materials for rechargeable lithium-ion batteries. J Power Sources 2013;236:188-91.

33. Li C, Yin C, Mu X, Maier J. Top-down synthesis of open framework fluoride for lithium and sodium batteries. Chem Mater 2013;25:962-9.

34. Parkinson MF, Ko JK, Halajko A, Sanghvi S, Amatucci GG. Effect of vertically structured porosity on electrochemical performance of FeF2 films for lithium batteries. Electrochim Acta 2014;125:71-82.

35. Duttine M, Dambournet D, Penin N, et al. Tailoring the composition of a mixed anion iron-based fluoride compound: evidence for anionic vacancy and electrochemical performance in lithium cells. Chem Mater 2014;26:4190-9.

36. Tan J, Liu L, Hu H, et al. Iron fluoride with excellent cycle performance synthesized by solvothermal method as cathodes for lithium ion batteries. J Power Sources 2014;251:75-84.

37. Li B, Cheng Z, Zhang N, Sun K. Self-supported, binder-free 3D hierarchical iron fluoride flower-like array as high power cathode material for lithium batteries. Nano Energy 2014;4:7-13.

38. Lu Y, Wen ZY, Jin J, Wu XW, Rui K. Size-controlled synthesis of hierarchical nanoporous iron based fluorides and their high performances in rechargeable lithium ion batteries. Chem Commun 2014;50:6487-90.

39. Lu Y, Wen Z, Jin J, Rui K, Wu X. Hierarchical mesoporous iron-based fluoride with partially hollow structure: facile preparation and high performance as cathode material for rechargeable lithium ion batteries. Phys Chem Chem Phys 2014;16:8556-62.

40. Ma D, Wang H, Li Y, et al. In situ generated FeF3 in homogeneous iron matrix toward high-performance cathode material for sodium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2014;10:295-304.

41. Hua X, Robert R, Du L, et al. Comprehensive study of the CuF2 conversion reaction mechanism in a lithium ion battery. J Phys Chem C 2014;118:15169-84.

42. Bao T, Zhong H, Zheng H, Zhan H, Zhou Y. In-situ synthesis of FeF3/graphene composite for high-rate lithium secondary batteries. Electrochim Acta 2015;176:215-21.

43. Zhao T, Li L, Chen R, et al. Design of surface protective layer of LiF/FeF3 nanoparticles in Li-rich cathode for high-capacity Li-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2015;15:164-76.

44. Hu X, Ma M, Mendes RG, et al. Li-storage performance of binder-free and flexible iron fluoride@graphene cathodes. J Mater Chem A 2015;3:23930-5.

45. Li A, Wu S, Yang Y, Zhu Z. Structural and electronic properties of Li-ion battery cathode material MoF3 from first-principles. J Solid State Chem 2015;227:25-9.

46. Bai Y, Zhou X, Jia Z, et al. Understanding the combined effects of microcrystal growth and band gap reduction for Fe(1-)TiF3 nanocomposites as cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Nano Energy 2015;17:140-51.

47. Chen C, Xu X, Chen S, et al. The preparation and characterization of iron fluorides polymorphs FeF3·0.33H2O and β-FeF3∙3H2O as cathode materials for lithium-ion batteries. Mater Res Bull 2015;64:187-93.

48. Li L, Jacobs R, Gao P, et al. Origins of large voltage hysteresis in high-energy-density metal fluoride lithium-ion battery conversion electrodes. J Am Chem Soc 2016;138:2838-48.

49. Jiang J, Li L, Xu M, Zhu J, Li CM. FeF3@thin nickel ammine nitrate matrix: smart configurations and applications as superior cathodes for Li-ion batteries. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016;8:16240-7.

50. Rui K, Wen Z, Lu Y, Shen C, Jin J. Anchoring nanostructured manganese fluoride on few-layer graphene nanosheets as anode for enhanced lithium storage. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2016;8:1819-26.

51. Hu J, Zhang Y, Cao D, Li C. Dehydrating bronze iron fluoride as a high capacity conversion cathode for lithium batteries. J Mater Chem A 2016;4:16166-74.

52. Rao R, Pralong V, Varadaraju U. Facile synthesis and reversible lithium insertion studies on hydrated iron trifluoride FeF3·0.33H2O. Solid State Sci 2016;55:77-82.

53. Rui K, Wen Z, Jin J, Huang X. Controlled construction of 3D hierarchical manganese fluoride nanostructures via an oleylamine-assisted solvothermal route with high performance for rechargeable lithium ion batteries. RSC Adv 2016;6:27170-6.

54. Sun H, Zhou H, Xu Z, Ding J, Yang J, Zhou X. Preparation of anhydrous iron fluoride with porous fusiform structure and its application for Li-ion batteries. Microporous Mesoporous Mater 2017;253:10-7.

55. Li Y, Yao F, Cao Y, Yang H, Feng Y, Feng W. The mediated synthesis of FeF3 nanocrystals through (NH4)3FeF6 precursors as the cathode material for high power lithium ion batteries. Electrochim Acta 2017;253:545-53.